The Price of Promises Made

What New York City Should Do About Its $95 Billion OPEB Debt

Imagine you were provided a credit card with no spending limit, and the lender did not require any short-term payments toward the charges you incurred. Rather, the lender required that your children and grandchildren pay back your charges plus accumulated interest in about 20 years. Facing no spending limit and no need to pay would you use the card extensively, or would you reject using this credit card because its terms were unfair to your children and grandchildren?

New York City’s municipal leaders have an analogous choice, and they have taken the former option. They have run up a tab of more than $95 billion and continue to charge about $5 billion more annually to this bill. The current debt equals about $30,000 for each household in New York City, and the burden will continue to grow without changes to current policies.1

The credit card used by municipal leaders is known as OPEB: other postemployment benefits. These benefits represent a part of the compensation for people who work for the City of New York, just like salaries and other fringe benefits. OPEB are benefits promised to police officers, firefighters, teachers, and other civil servants who provide public services each day. The City promises them benefits in the future–and charges the promise on the credit card. Specifically, a variety of health insurance benefits promised to these workers when they retire are not paid for as they work, but are to be paid for in the future when they reach retirement age. The taxpayers having to foot those bills, at prices likely to be notably higher than their current cost, will be the next generation of New York City taxpayers.

This current OPEB financing arrangement violates a principle termed “intergenerational equity” which requires those who receive and consume services to pay for them rather than pass the cost on to future generations. This report examines the magnitude and nature of this fiscal problem that has been left unaddressed for decades. It also suggests strategies for reducing this financial burden on current and future generations by better aligning New York City’s OPEB with other municipalities’ benefits and establishing more appropriate arrangements for funding those benefits.

How New York Got So Deep in Debt

Retirement benefits have long been an attractive feature of public sector employment, and this has been especially true in New York City. For nearly 100 years the City’s employees have been promised substantial pensions upon retirement. The financing of these pension benefits was made relatively secure through the creation of dedicated fiduciary funds separate from the City’s general finances. The City, as employer, and the employees make contributions to the pension funds, and the money is invested to generate additional future funds. The required size of the current annual contributions from the City is substantial, about $9.4 billion, or 11 percent of General Fund expenditures, in fiscal year 2017, but the willingness of current City officials to allocate these funds enables the pension funds to be relatively sound over the long term. Even more funding may be required in the future to support pension benefits, but the strategy of creating dedicated pension funds with substantial assets and potential future earnings is a widely accepted one for sound financing of these promised employee benefits.

Health insurance for retirees suffers from less sound financing. Health insurance became a common fringe benefit for workers in the mid-20th century, and Mayor LaGuardia established an innovative plan for municipal employees—the Health Insurance Plan of Greater New York, or HIP.2 When the City offered health insurance coverage for the first time in 1946, the cost was shared equally between employees and the City. This plan was subsequently modified with greater choices for workers and a commitment by the City to pay the equivalent of the full cost of the HIP plan toward coverage under the alternative plans which were somewhat more expensive. Coverage was extended to retirees in the 1960s, initially with some premium cost sharing; after passage of the federal Medicare program for those over age 65, eligible retirees were required to enroll in that program and offered supplemental coverage with no premium cost sharing. Beginning in 1968 the City reimbursed retirees for their required Medicare Part B premiums. At the time, these premiums totaled $4 per beneficiary per month and few anticipated health cost inflation would escalate the way that it has.

The funding mechanism for retiree health insurance benefits did not follow the model used for pension benefits; that is, dedicated fiduciary funds established in advance with employer and employee contributions. Instead, it followed the model used for health insurance for current employees. The City paid the annual premium for current employees and current retirees in the year it was due in order to cover those currently eligible for insurance. The costs of promised benefits for future retirees were not provided for or taken into account. This pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) arrangement was the norm across the United States for state and municipal governments. By 2000 New York City paid out nearly $458 million for retiree health insurance benefits, or about $2,536 annually per retiree.3 By 2005 this amount had nearly doubled to more than $913 million, or about $4,611 annually per retiree.4

In 2006 the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), the independent entity that sets rules for state and local governmental accounting, required that the accounting approach for retirement benefits other than pensions (which is largely retiree health benefits) be aligned with that used for pensions. GASB Statement 45 required governments to report the following items for OPEB benefits:

- Actuarial Accrued Liability (AAL): the estimated future cost of benefits promised to current retirees and current employees when they retire;

- Actuarial Asset Value (AAV): the value of assets set aside to fund these future benefits;

- Unfunded Actuarial Accrued Liability (UAAL): the difference between the future cost (AAL) and available assets (AAV);

- Normal Cost (NC): the current year’s incremental accrued cost of benefits for current employees;

- Annual Required Contribution (ARC): the amount the government would be required to pay each year to cover the Normal Cost plus the unfunded portion (UAAL) over a 30-year period.

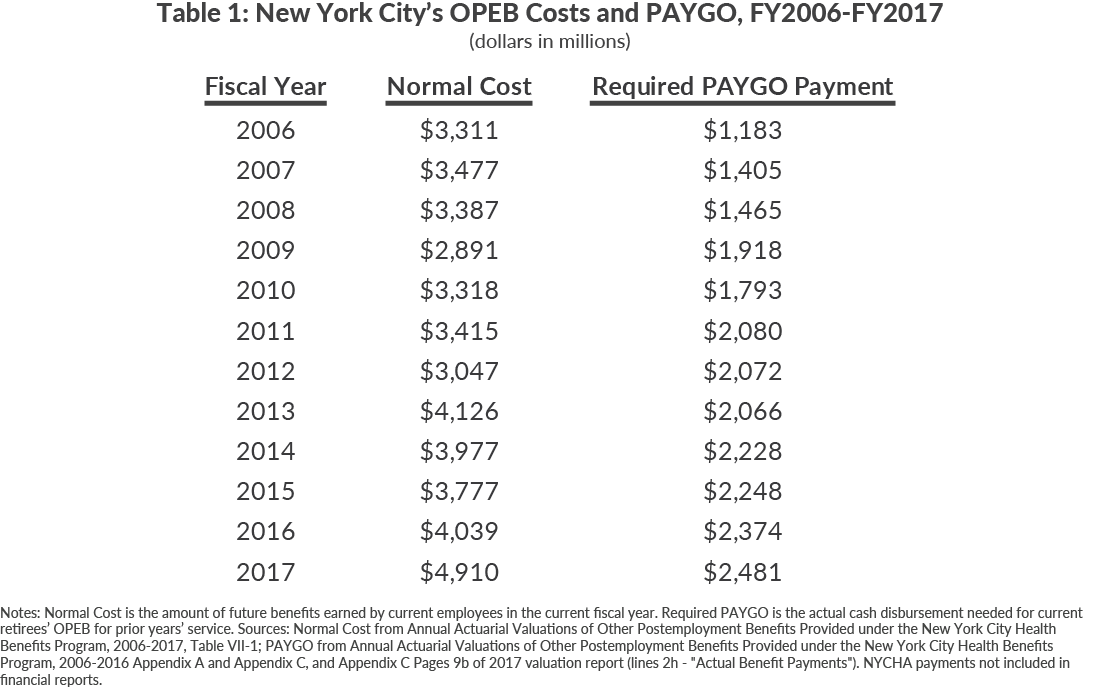

When the new GASB rules took effect in 2006, the City had to account for the OPEB benefits it had offered since the late 1960s without prefunding. The normal cost–the future benefits earned in 2006 by current employees—totaled more than $3.3 billion in 2006, while the actual cash payouts to fund current retiree benefits exceeded $1.1 billion. These amounts have fluctuated annually, but have grown to nearly $5 billion annually for the normal cost and nearly $2.5 billion for the actual cash PAYGO. (See Table 1.)

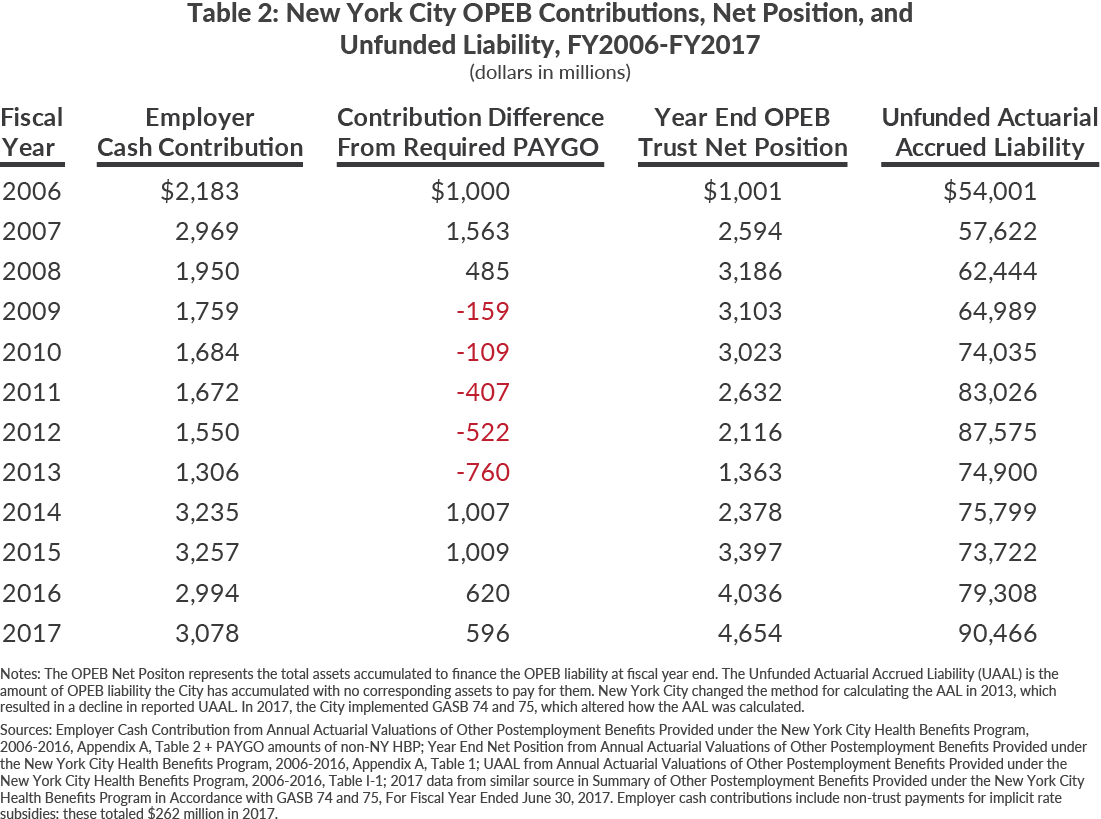

The City created a dedicated fund for OPEB benefits in 2006, known as the Retiree Health Benefits Trust (RHBT), when the new GASB rules became effective. In this first year, the City reported its UAAL at $54.0 billion. That is, the unfunded cost to New York City for future retiree benefits (those already earned by current retirees as well as current workers) was valued at $54.0 billion.5 The UAAL grew nearly 5 percent annually through 2009, when it reached a reported $65 billion. The City’s UAAL jumped more than $9 billion in 2010, largely attributable to federal health care reform that increased benefits (for example, permitting adult children to remain on parents’ insurance until age 26), and a New York State extension of COBRA benefits from 18 to 36 months.6 The UAAL jumped again nearly $9 billion in 2011, due to changes in actuarial assumptions that increased life expectancy, and thereby increased what the City owed.7

In 2013 the reported UAAL dropped more than $12 billion due to a technical change in how the liability itself was calculated.8 From 2013 to 2016, the UAAL only increased 6 percent in total, which represents an annual growth rate of less than 1.5 percent. The decline in UAAL growth is attributable in part to slower growth in health care costs than predicted, and increased prefunding to the RHBT. In 2017 New York City implemented GASB 74 and 75, which changed (among other factors) the discount rate used to calculate the AAL. The rate was lowered, which caused the reported UAAL to increase as a result. Since 2014 more than $3 billion in total has been added to the trust. (See Table 2.)

Although OPEBs are commonly summarized as “retiree health insurance,” the benefit package in New York City has five components. Each is described below.

Medical and Hospital Insurance for Retirees Not Yet Eligible for Medicare

One benefit is the payment of insurance premiums for comprehensive medical and hospital insurance. Retirees who worked for City government for at least 10 years (15 years for teachers) are eligible for this benefit through the New York City Health Benefits Program.9 Retirees not yet eligible for Medicare are eligible for coverage essentially identical to that available to current employees and their dependents.10 New York City pays the entire health insurance premium as long as the retiree participates in HIP HMO or GHI/EBCBS, and more than 95 percent of participants elect one of these options.11 In fiscal year 2017 these insurance policies cost New York City approximately $7,200 for individuals and $17,600 for families annually.12

Medicare Supplemental Benefits

When retirees reach Medicare eligibility (typically at age 65), they are required to enroll in Medicare. The federal program provides substantial benefits, but has significant deductibles and copayment requirements; the City program pays the premiums for policies providing Medicare supplemental benefits through the same insurance companies providing its basic benefits, largely GHI and HIP, usually at no cost to the retiree. These premiums cost the City approximately $1,900 for individuals and $3,900 for families in fiscal year 2016.13 More than 96 percent of Medicare-eligible retirees choose one of these options.14 These supplemental plans significantly reduce retirees’ out-of-pocket health care costs.

Medicare Part B Reimbursement

Enrollment in Medicare is associated with a monthly premium the retiree must pay to the federal government, usually through a deduction from Social Security benefit checks, for Medicare Part B, which covers medical expenses. The required premium changes annually and varies with income; as of 2017, the minimum is $134 monthly, and it can be as high as $429 monthly or between $1,608 and $5,143 annually. However, one of the OPEB benefits is reimbursement from the City for any required premium, including the additional premiums charged to high-income retirees through the Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amounts (IRMAA).15 New York City reimburses municipal retirees for all Medicare Part B premiums paid in the prior calendar year (that is, reimbursement for the current fiscal year occurs in the next fiscal year). This amount will increase as Medicare Part B premiums increase over time.

Union Welfare Fund Benefits

An additional OPEB benefit is contributions to union welfare funds by the City on behalf of retirees. More than 100 welfare funds administered by municipal labor unions provide retired members benefits such as prescription drug coverage, vision and dental coverage, and non-health benefits such as life insurance, accidental death or disability insurance, and legal services. In fiscal year 2017, the amount of welfare fund contributions varied by union, but generally ranged from slightly less than $1,600 to nearly $1,800 per retiree.16

Cadillac Tax for Generous Health Care Benefits

The federal government is authorized under the Affordable Care Act of 2010 to impose a “Cadillac Tax” on employers who provide unusually generous health insurance benefits. This tax was initially scheduled to become effective in 2018, but has been delayed until 2020. When the tax takes effect, the City’s OPEBs are expected to be subject to it, and the City will pay the tax to the federal government.

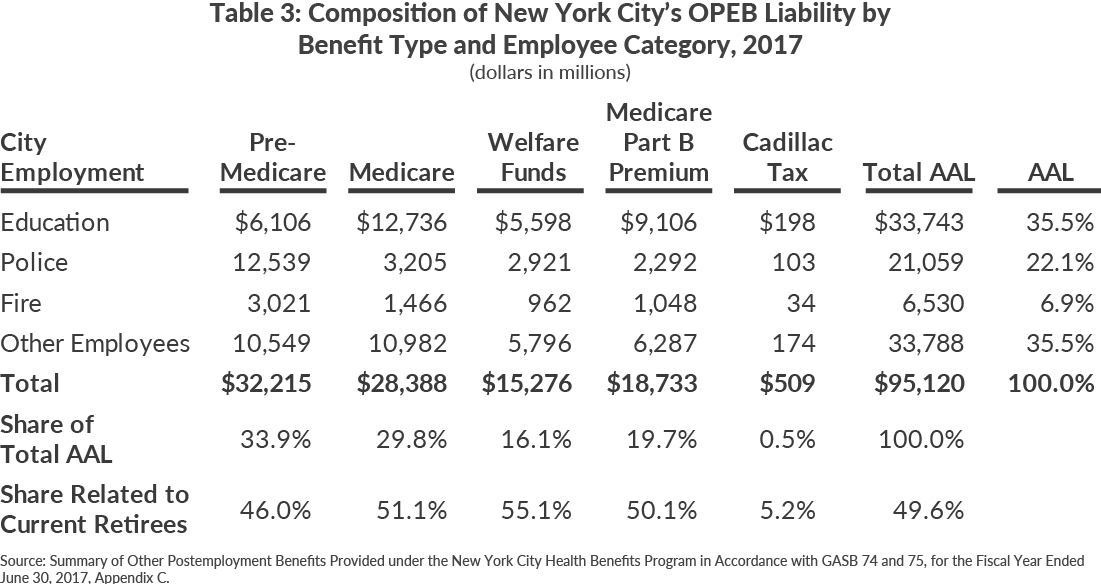

Table 3 summarizes how the $95 billion OPEB AAL is divided among these five benefit components. About $32.2 billion, or 34 percent, is required to pay health insurance premiums for retirees who have not reached age 65, and another $28.4 billion, or 30 percent, is required to pay the premiums for supplementary insurance for those enrolled in Medicare. Reimbursing retirees for their Medicare Part B premiums accounts for more than $18.7 billion, or 20 percent, and the promised union welfare fund contributions are another $15.3 billion, or 16 percent. The Cadillac tax represents less than 1 percent of the liability.

New York City’s OPEB liability is nearly equally divided between current employees and those already retired. Table 3 also reports the share of each OPEB component for those who are currently retired.

The accumulated cost of promised health benefits is not divided equally among all municipal workers. Although their health-related benefits are generally similar, variation in costs arise because their pension plans vary—which permits some categories of workers to retire earlier than others and thus receive benefits for a longer period of time. Police officers and firefighters are eligible to retire after 20 years of service (or 22 years if hired after 2009) with no age threshold; many retire in their 40s and receive benefits for 30 or more years. Teachers and other education employees are eligible for more generous pension benefits than other non-uniformed municipal employees, so teachers tend to leave earlier and have longer periods of retirement than their civilian counterparts.17

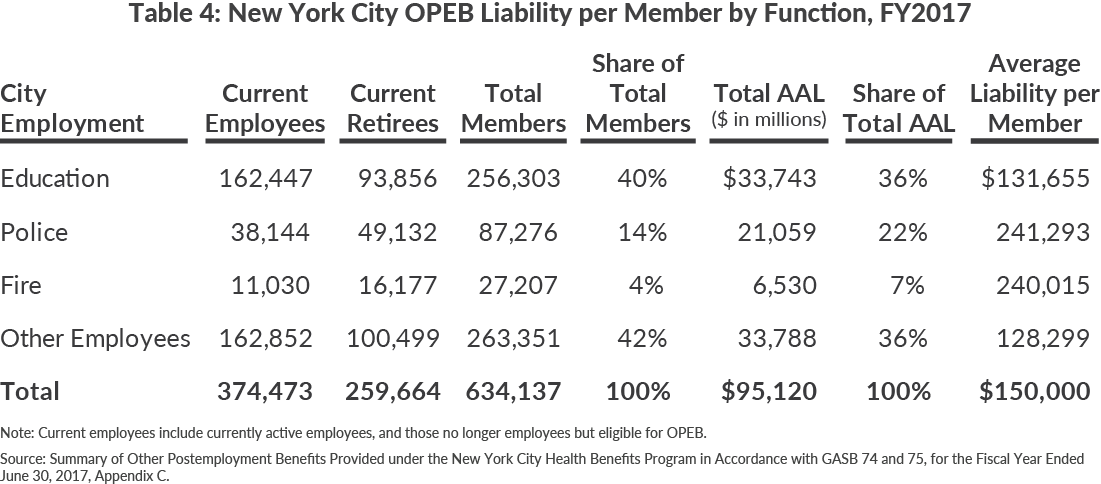

As shown in Table 4, the $95.1 billion AAL is attributable to 374,473 current employees and 259,664 retirees for a total of 634,137 members, an average of $150,000 per person. Although police officers and firefighters account for only about 18 percent of the employees and retirees, their share of the AAL is nearly 30 percent; the per member liability for these groups are over $241,000 and $240,000 respectively— or nearly double that for the other non-education City employees.18

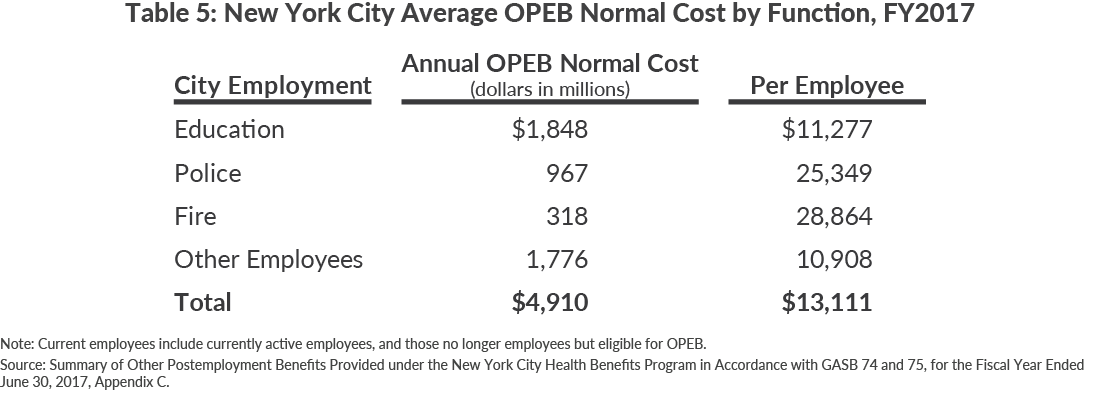

Another revealing indicator of the variability in cost among types of workers is the normal cost for benefits of each group. As noted earlier, normal cost gauges the cost of the retirement benefits workers have earned in the current year. Each police officer earns $25,349 in promised OPEB annually; for firefighters the promised amount is $28,864. Education workers and other civilians have a normal cost less than half that of police officers and firefighters, $11,277 and $10,908 respectively. (See Table 5.)

The relative importance of the benefit components varies substantially among groups of workers. The largest source of variability is insurance premiums for workers who retire before reaching age 65 and qualifying for Medicare. Among police officers this accounts for fully 60 percent of the OPEB liability, and for firefighters the share is 46 percent; in contrast “early” retirees’ insurance premiums account for less than one-third the liability for most civilian workers and only about one- fifth the liability for education staff. The large share for police and firefighters is related to their eligibility for retirement based only on years of service and not age. Similarly reimbursement for Medicare Part B premiums accounts for only 11 percent of the liability for police officers, but more than one-quarter of the liability for education personnel. The share of liability attributable to union welfare fund contributions varies relatively little near the 17 percent average, reflecting the similar amounts paid for each type of worker.

Why New York City Is More Indebted Than Most Other Cities

New York City is not the only large city to promise OPEB benefits, yet its unfunded liability is much greater than that of other state and local governments. The Center for Retirement Research (CRR) estimated in 2016 that the total state and local government unfunded OPEB liability was more than $862 billion.19 Because most governments (except New York City) chose to amortize past OPEB liabilities over 30 years in 2006 rather than recognize the full liability immediately, this $862 billion reflects only a portion of currently outstanding liabilities. Assuming prior amortization patterns continue, this implies current OPEB liabilities outstanding are closer to $1.3 trillion nationally, equivalent to 55 percent of state and local government spending on current operations.20

CRR further estimates that approximately two-thirds of the unfunded liability is the responsibility of local (as opposed to state) governments. This reflects not only the distribution of total employment between the two levels, but also correlates with the type of workers–notably police officers, firefighters, and teachers–who receive relatively generous OPEB benefits; all are typically local government employees.

Because local governments vary in size, comparing the OPEB liability of cites is most meaningfully done on a per member (employees and retirees) basis. However, even these comparisons are potentially misleading. Cities vary in their functions, with some such as New York performing all functions of cities, counties, and independent school districts in other metropolitan areas. Generally in other large cities, teachers are employed by separate school districts and some functions, such as welfare administration, are performed by the state or separate counties.

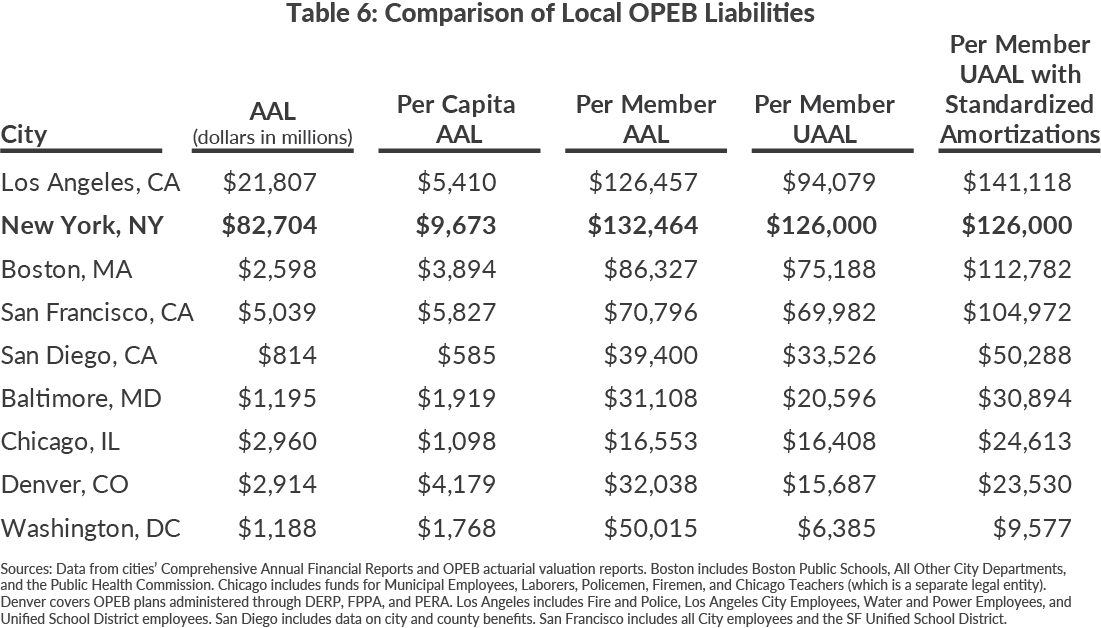

Table 6 presents estimates of OPEB liabilities in New York and eight other large, unionized cities. The analysis focuses on data from 2016 because data from 2017 are not yet available from most cities. To facilitate comparisons, the data in the table are adjusted to reflect a common pattern of amortization and to take into account the overlapping government units serving a particular area.21 New York’s per member UAAL is larger than that for all other cities except Los Angeles, ranging from nearly five times that of Chicago to more than 10 percent greater than in Boston.

Los Angeles illustrates the difficulties of comparing OPEB liabilities across jurisdictions. Residents of the City of Los Angeles are served by multiple local governments including a city, an independent school district, and a county. The county and school district have larger boundaries than the city, so their liabilities reflect the costs of serving more people than does the city government. Moreover, the city has separate pension and OPEB arrangements for its civilian workers, police officers, and firefighters. Although the City of Los Angeles is notable for its practice of employer prefunding much of the OPEB liability for its civilian workers, it does not fully fund OPEB benefits for police officers and firefighters (who have separate benefit plans), and the school district has virtually no prefunding of OPEB benefits for its employees. The combined result, heavily influenced by the large number of teachers involved, is a combined per member UAAL of more than $141,000 when adjusted for amortization.

New York City’s unusually large OPEB liability is due primarily to its relatively costly benefit package. According to a 2013 study, only 27 of 61 cities analyzed had even partially prefunded their OPEB liabilities.22 The pattern in other cities is similar to that in New York: advance funding is made on a discretionary basis with infrequent and modest contributions.

The dominant reason for lower liabilities in other cities is that their promised benefits are less costly. This has been the case for a long time, but it has become even more significant due to recent efforts by other cities to lower their retiree benefit costs.

A 2013 study by the Citizens Budget Commission compared retiree health benefits of New York City with those of the federal government, the State of New York, and six other large cities: Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston, Phoenix, and Houston.23 None of the other jurisdictions matched New York City’s policy of covering 100 percent of the premium for both individual and family coverage and reimbursing the full cost of Medicare Part B premiums for retirees and spouses. For federal retirees, their share of premium costs was about 25 percent and no Medicare reimbursement was provided; for New York State retirees, the required premium contribution was at least 12 percent for individual and at least 27 percent for family coverage – which both included Medicare premiums reimbursements. Among the six cities, three (Chicago, Houston, and Phoenix) required substantial premium contributions from retirees (between 40 percent and 86 percent) and offered no Medicare reimbursement; Boston required premium sharing of between 17.5 and 27.5 percent depending on the plan selected and reimbursed one-half the Medicare premium. San Francisco required no contribution for individual coverage but cost sharing of 12 to 35 percent for family coverage (depending on the plan selected) and provided no Medicare reimbursement. Los Angeles paid the full premium for individual and family coverage for retirees with at least 25 years of service, but those with 10 to 25 years of service paid a share based on length of service that rose to 80 percent for those with just 10years; Los Angeles offered Medicare reimbursement only for retirees (not spouses) and only for the standard (not high income) rate.

Other large cities not included in the prior CBC study also provide less generous benefits to retirees than New York City does. In Denver retirees pay the premium (which is lower because of an implicit rate subsidy), which is offset at a fixed amount per year of service, and the amount declines after the retiree is eligible for Medicare.24 Retirees use the benefit to reduce their cost of health insurance (or Medicare supplements if Medicare-eligible) in retirement, and can use this benefit toward spousal and dependent insurance as well.25 Washington, D.C. pays only 25 percent of the premium for teachers and general city workers, and 30 percent for police officers and firefighters. Washington, D.C. also pays a smaller share, 20 percent and 25 percent, for covered family members.26

Many of these cities–already with less generous benefits than New York City–have further limited the benefits of retirees in recent years. Mayor Rahm Emanuel of Chicago proposed eliminating OPEB benefits for City workers for anyone who retired after 1989, beginning in 2014 and terminating all retiree health care plans by 2017. The outcome of Chicago’s OPEB reform is still uncertain and remains in litigation.27 Baltimore increased employees’ share of health care costs and is sun-setting drug benefits for retirees in 2020.28 Spouses and dependents may continue coverage after a retiree dies by paying 102 percent of the stated policy premium. The changes were made to all employees and current retirees’ benefits, not just new employees.

In 2012 San Diego implemented a transition from a defined benefit OPEB plan to a defined contribution OPEB plan, dependent upon a retiree’s years of service.29 The old defined benefit OPEB plan included family members if the retiree paid for them, and the new defined contribution OPEB plan allows retirees to use funds to purchase family coverage.

The City of Detroit entered formal Chapter 9 bankruptcy proceedings in 2013. When its plan for adjustment was approved in 2014, retiree health benefits were slashed as part of the resolution. Current and future retirees absorbed cuts upward of 90 percent of expected benefits. The beneficiaries of Detroit’s OPEB system fared similarly to those of Stockton, California which exited bankruptcy around the same time as Detroit. In this case, OPEB benefits were also reduced by more than 90 percent.30

Retiree Health Benefits in the Federal Government

Individuals who retire from the federal government before Medicare-eligible may obtain health insurance for themselves and their families. Unlike New York City, however, these individuals must pay for 25 percent of the premium cost on their own.31 Further, the federal government does not reimburse retirees for Medicare Part B premiums. In addition, the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) was required to account for its OPEB and begin making payments in 2006. Ever since these payments began, the USPS has run an operating deficit. In 2015 alone, the USPS reported $125 billion in debt, mostly for unfunded pensions and OPEB. Retirement benefits contribute significantly to the USPS’s insolvency.

Retiree Health Benefits in the Private Sector

The private sector has experienced a significant withdrawal from offering retiree benefits over time, due in large part to how expensive these benefits are. In 1988 nearly two-thirds of large firms offered some form of retiree health benefits; this percentage has fallen to 24 percent in 2016.32 However, nearly one-half of large firms defined as those employing 5,000 or more workers offer such benefits. Of these firms offering insurance, 92 percent do so for those who are not yet eligible for Medicare, and the percentage drops to 72 percent for those who are Medicare-eligible. Further, 45 percent of large firms offering benefits were considering changes to these benefits.33 Importantly, however, most of these firms require cost sharing with retirees (full or partial); only 12 percent of large employers report paying the full amount.34

General Motors (GM), for example, began offering retiree health insurance even before New York City did. In the 1950s, the company began paying for all costs associated with retiree health insurance. By 2004 GM had deposited $20 billion into a trust, but obligations were close to $77 billion.35 This liability exceeded the company’s market cap, and the company was forced to shed the liability to a Voluntary Employee Benefit Association (VEBA) to manage the OPEB and limit its own exposure.

How to Reduce the Burden on the Next Generation

New York City’s elected leaders should reverse the current policy of steadily increasing the burden on future taxpayers and begin addressing the fiscal reality of OPEB. A successful approach must include two interdependent strategies: First, the cost of the benefit package should be reduced significantly. Second, once the cost is reduced, more substantial and systematic prefunding policies should be established and implemented.

A More Affordable Benefit Package

Multiple features make the City’s current retiree benefits uniquely expensive relative to other municipalities - including the 100 percent premium payments for early retirees and their spouses, the 100 percent premium payments for supplementary Medicare coverage for retirees and their spouses, and the full reimbursement of Medicare Part B premiums for retirees and their spouses. Given this expensive set of benefits, a suitable goal is to cut the taxpayer cost in half. Reforms should reduce the normal cost for current workers and the PAYGO amount for current retirees by at least 50 percent each. The current normal cost is nearly $4.9 billion annually, so this implies reducing this cost by nearly $2.5 billion annually; the PAYGO amount is currently $2.5 billion, which implies reducing this cost by approximately $1.25 billion annually.

Such substantial savings cannot be achieved by following the precedents established in efforts by the State and City to contain the cost of pension benefits. Because these benefits are protected by State constitutional provisions, any pension benefit reduction can apply only to workers hired after the changes are enacted. Because OPEB liabilities exist for current workers and retirees, changes for newly hired workers have minimal impact on PAYGO and normal costs for at least a generation. To achieve the targeted savings, changes are essential for benefits received and earned by current employees and retirees.

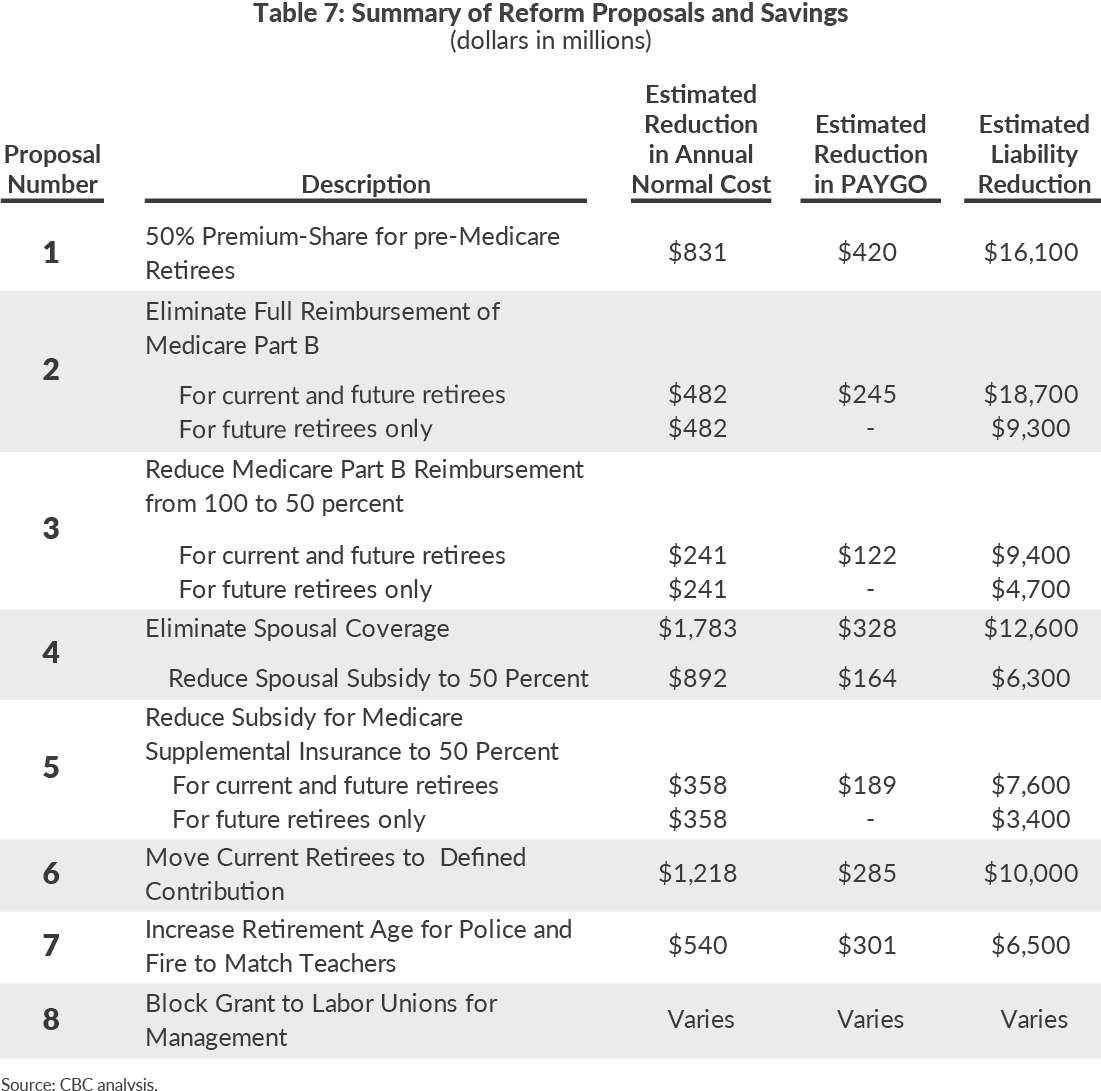

Table 7 summarizes the fiscal impact of eight options to revise the benefit package. Many of these proposals share the cost of OPEB with employees, which is how New York City’s OPEB benefits were originally structured in the 1960s. Further, moving to such a cost sharing arrangement would better align New York City’s OPEB with other large municipalities’.

- Require workers who retire before Medicare eligibility to pay 50 percent of their health insurance premium. This reform would reduce the normal cost by approximately $831 million annually and lower current annual spending by approximately $420 million. This option would also eliminate about $16.1 billion—nearly 17 percent of the total—of OPEB liabilities.

- No longer reimburse for Medicare Part B premiums. This would eliminate about $482 million in annual normal costs, and lower current annual outlays by at least $245 million. This reform would also eliminate about $18.7 billion—or about 20 percent of the total—of OPEB liabilities. If the benefit were terminated only for future retirees, that is, current city workers, the change would lower the liability by $9.3 billion.

- A more incremental change to the Medicare Part B reimbursement benefit is to lower it from full reimbursement to 50 percent reimbursement. Under current Medicare rates, this would require most retirees to pay about $61 monthly. This reform would lower the normal cost by about $241 million annually and about $122 million in current outlays. This change would reduce the OPEB liability by $9.4 billion, or 10 percent, if applied to all current and future retirees and about $4.7 billion, or 5 percent if applied only to future retirees.

- End benefits for spouses of retirees. This reform would reduce the normal cost approximately $1.78 billion annually and $328 million in current outlays. About $12.6 billion or 13 percent of the OPEB liability is for current retiree spousal benefits.36 A 50 percent cost share on this reform would reduce these savings by one-half.

- Reduce to 50 percent the premium payments for Medicare supplemental insurance. This reform would reduce the normal cost by approximately $358 million annually and $189 million in current annual outlays. This reform would also eliminate about $7.6 billion, or 8 percent, of the outstanding OPEB liability.

- Replace the full premium payments on behalf of retirees and spouses with a voucher to be used for purchase of insurance. Nearly $30 billion of the OPEB liability is for premiums for retirees who are not yet eligible for Medicare. The average OPEB cost is $10,950 per year, or $912 per month. Providing a voucher for $600 per month per individual would provide reasonable access for retirees to most options either on the State exchange or offered directly from New York City without an excessive burden. This reform is estimated to save about $1.2 billion in normal cost if applied to current workers and $285 million in current outlays if applied to current retirees. This reform would reduce the OPEB liability about $10 billion, or 11 percent, although less if annual inflation adjustments were made to the voucher value.

- Increase the retirement age for police and firefighters to match teachers’ retirement age of 55. Currently, police and fire may retire after 22 years of service. The average retirement age for police is approximately 48, and for fire it is 47. Increasing the retirement age would reduce the pre-Medicare AAL and reduce the normal cost and PAYGO in the process. This reform is estimated to reduce the annual normal cost approximately $518 million and reduce the PAYGO about $289 million. Nearly $6.3 billion in OPEB liability would also be eliminated.

- Provide a fixed payment to municipal employee unions and authorize them to provide retiree health benefits. The City already makes payments to welfare funds for some health benefits, and it negotiates the benefit package with the Municipal Labor Committee (MLC). The City could provide the Coalition or its constituent units funding equal to the current annual PAYGO amount of $2.5 billion. Future amounts could be held constant or kept below the prior growth rate in OPEB costs. If the unions could find savings, they would keep it. Changes to benefits would come from labor initiatives, not from renegotiations with the City.

The above is a menu of options. It provides a basis for constructing a package of reforms that can achieve the recommended goal of cutting the taxpayers’ costs in half. For illustrative purposes, if the City were to require 50 percent premium cost sharing on pre-Medicare insurance, Medicare Part B reimbursements, spousal coverage, and Medicare supplemental coverage, the annual normal cost would be reduced approximately $2.3 billion, current outlays reduced $900 million annually, and the liability reduced $39.4 billion, about 41 percent of the total. If the City required a 50 percent cost sharing on these items but eliminated Part B reimbursements altogether, the normal cost would be reduced approximately $2.6 billion annually, current outlays reduced slightly more than $1 billion annually, and the liability reduced $48.7 billion, or about 52 percent of the total. These reforms would still leave New York City with OPEB benefits more expensive and expansive than other cities’ benefits, but the taxpayer burden would become more manageable.

Changes in health benefits for employees and retirees are mostly subject to collective bargaining and must be agreed to by union leaders. The Mayor, whose staff negotiates for the City, should exercise leadership in articulating to the public and the municipal workforce the case for benefit revisions, and union representatives should recognize that the sustainability of their benefits requires a new approach that does not rely so heavily on the next generation to pay for what they are promised today.

Enhanced Prefunding Policies

Even if the city’s elected and union leaders are successful in revising the retiree benefit package to be more affordable and consistent with practices in other jurisdictions, New Yorkers will still confront a sizeable OPEB liability. Postponing the day of reckoning for this bill is not only objectionable as a violation of intergenerational equity, but it will also create a massive, practical fiscal problem. Continuing to pay for retiree benefits on a PAYGO basis will eventually cause the current annual cost to reach a level that diverts needed resources from other municipal needs and that exceeds what would have been required if prefunding was implemented on a more systematic basis than is currently the case.

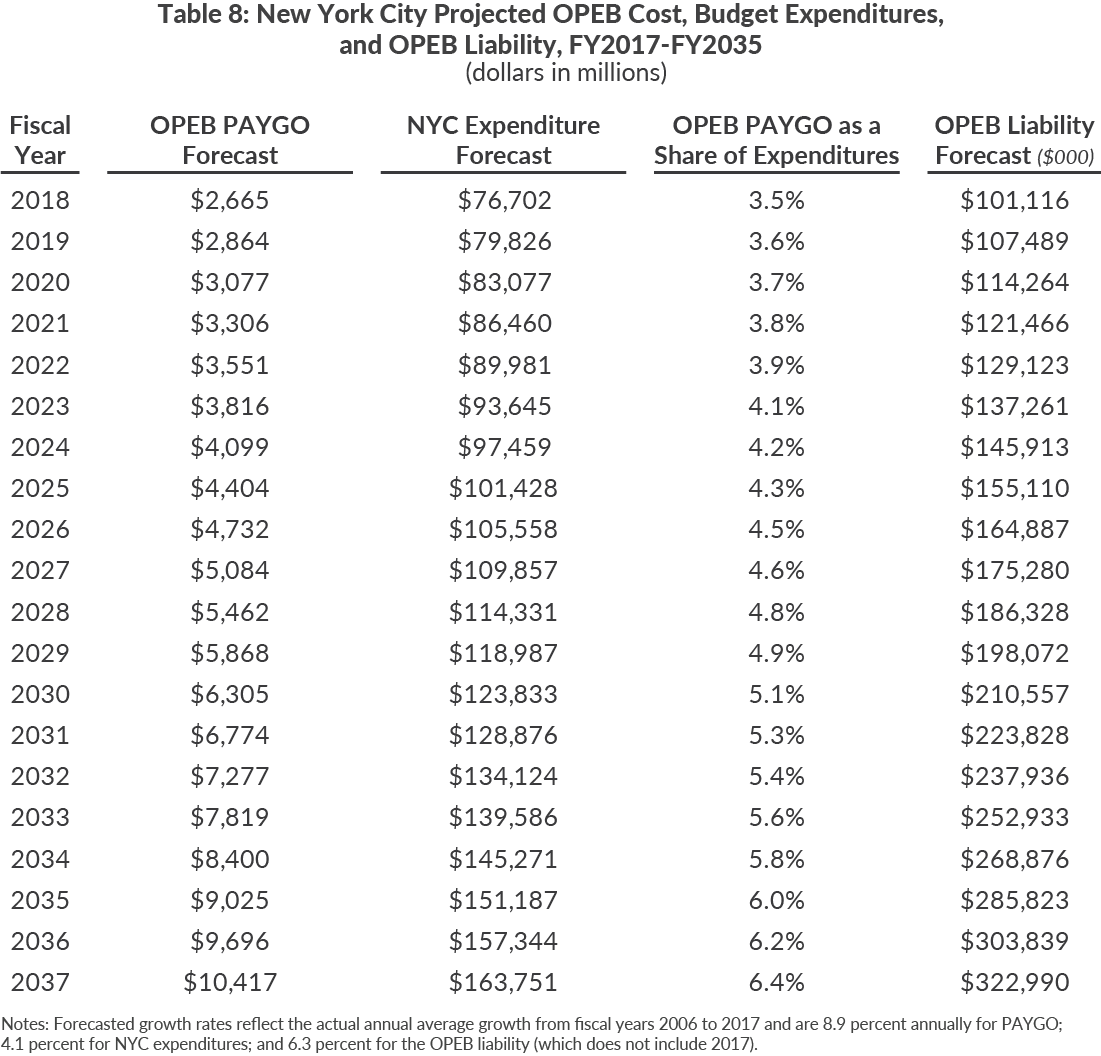

Under current policies the annual outlays for retiree benefits will in several years likely consume a growing and substantial portion of total municipal expenditures. Table 8 presents projections of the annual PAYGO expenditures for retiree health benefits on the assumption they continue to grow at the rate of the past 10 years; by 2027 they will have grown from the 2017 level of $2.5 billion to more than $5 billion and by 2037 nearly $10.5 billion. If total municipal expenditures also continue to grow at the rate of the last 10 years, then retiree health benefit costs will rise from less than 3.2 percent of all spending to nearly 6.4 percent by 2037.

The current approach to prefunding is inadequate because there is no consistent policy for deposits and withdrawals from the RHBT. Instead the fund has been used more as a rainy day or discretionary fund with no clear goal of creating a large reserve that can achieve meaningful earnings.

The City deposits money into this fund and pays for current retiree benefits from it. If the City deposits more than it withdraws for the annual cost of current beneficiaries, then it accumulates assets that can be invested to fund the accumulated unfunded liability. The appreciation of accumulated assets allows the City to contribute less in subsequent years. However, the amount the City deposits into the OPEB trust is decided upon on an ad hoc basis; no policy guides how much the City should contribute other than having sufficient funds to pay current year’s benefits.

Political leaders and City managers widely view the OPEB trust as a discretionary fund to smooth budgetary needs rather than accumulate the assets needed to pay for future benefits. For example, the trust is not investing long term. In 2017 about 67 percent of the total OPEB assets were invested in cash or cash equivalents (such as U.S. Treasury bills, commercial paper, and other short- term funds), and the remaining 33 percent are low-yielding liquid assets that are easily converted to cash. Since the trust’s inception in 2006, the City has contributed more than the PAYGO amount seven times, and failed to contribute PAYGO five times (from 2009-2013). In 2008, the trust had assets equal to 5.1 percent of liabilities. This declined to only 1.8 percent in 2013, and currently stands at 4.9 percent again. This reflects the inconsistent funding of the trust and the inconsistent asset holdings of the trust.

New policies should guide the management of the trust fund. Withdrawals should remain limited to the PAYGO cost of retiree benefits, but deposit should be set on a more systematic basis. A revised benefit package is essential to making a more prudent deposit policy fiscally practical.

Once benefit reforms significantly reduce costs, the City should deposit the normal cost into the trust annually. In addition, accrued balances should be invested for long-term gains and investment income should become part of the equation for reducing the future OPEB liability.

The basic policy for deposits should be a minimum amount equal to the normal cost as well as the PAYGO amount required for current retirees. This policy would not permit the City to defer current year costs for current employees into the future. Future costs will also be reduced as investment returns from accumulated assets add to the trust, and reduce or slow the growth in annual contributions required from the City.

Any concerns about the fiscal implications of a more aggressive deposit policy can be addressed through a circuit breaker provision for times of budgetary stress. Budgetary stress might be defined as revenues growing less than the inflation rate. In this situation the required OPEB deposit could be lowered in proportion to the revenue shortfall or even suspended. Under a City Charter amendment proposal intended to fund OPEB and introduced in 2015 by City Council Member Daniel Garodnick, a circuit breaker would kick in when revenue growth was less than 2 percent. In such a year no deposit would be mandated.

Conclusion

New York City’s leaders should revise their practices with respect to retiree health benefits. Effective reform requires two linked strategies. First, the cost of benefits promised by the City must be reduced to levels consistent with those available in other large cities. The scale of the savings should halve the cost, and this report has identified a range of options to achieve that goal. Second, more substantial and systematic prefunding arrangements should be implemented. Deposits should be made to a dedicated fund equal to the normal cost of the reduced benefits for current employees and the PAYGO cost for those benefits for retirees. This will permit the accumulation of funds for investments from which earnings can reduce future required taxpayer contributions.

Footnotes

- By way of contrast, unfunded pension liabilities average less than $21,000 per New York City household.

- See: Sheila Spiezio, Modernizing the Municipal Employee Health Insurance Program (Citizens Budget Commission, April 1995).

- CBC staff analysis of data from Office of the New York City Comptroller, New York City Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Fiscal Year 2001, Note E4, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/cafr2001.pdf.

- CBC staff analysis of data from Office of the New York City Comptroller, New York City Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Fiscal Year 2005, Note E4, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/cafr2005.pdf.

- OPEB is not an equivalent liability to pensions because they are not explicitly protected in the State constitution from being “diminished or impaired” (Article V, Section 7) (Lippman v. Board of Education of the Sewanhaka Central High District 1985). However, GASB accounting standards note that governments have “an obligation to pay OPEB based on the retirement benefits promised to an employee in exchange for his or her services.” In New York City, the benefits are within the scope of collective bargaining and represent an obligation of the City, and State law requires collectively bargained benefits to continue even after expiration until a new contract is agreed upon (the Triborough Amendment to the Taylor Law).

- Office of the New York City Comptroller, New York City Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year 2010, p. 9, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/cafr2010.pdf.

- Office of the New York City Comptroller, New York City Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year 2011, p. 9, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/cafr2011.pdf.

- In 2013 the City switched from the Frozen Entry Age actuarial cost method to the Entry Age actuarial cost method, resulting in a decline in reported liabilities.

- New York City Administrative Code Section 12-126. Employees of New York City’s component units (Educational Construction Fund, Health and Hospitals Corporation, New York City Housing Authority, School Construction Authority, and the Municipal Water Finance Authority) are also eligible for OPEB. These employees are included in this analysis because the City is ultimately financially responsible for them. These units are responsible for less than 8 percent of the total OPEB liability.

- Dependent coverage under City OPEB programs ends when a retiree dies except for spouses (for life) and children (to age 26) of police or fire who die in the line of duty. Other surviving spouses of police, fire, correction, and sanitation may continue coverage for life by paying 102% of the stated premium. City of New York, Office of the Actuary, Summary of Other Postemployment Benefits Provided under the New York City Health Benefits Program in Accordance with GASB 74 and 75, For Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017 (June 30, 2016), p. 4-5, http://www1.nyc.gov/site/actuary/reports/reports.page.

- City of New York, Office of the Actuary, Summary of Other Postemployment Benefits Provided under the New York City Health Benefits Program in Accordance with GASB 74 and 75, for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017 (June 30, 2016) p. 18, www1.nyc.gov/assets/actuary/downloads/pdf/OPEB_Report_FY2017.pdf.

- City of New York, Office of the Actuary, Summary of Other Postemployment Benefits Provided under the New York City Health Benefits Program in Accordance with GASB 74 and 75, for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017 (June 30, 2016), p. 19, www1.nyc.gov/assets/actuary/downloads/pdf/OPEB_Report_FY2017. pdf.

- City of New York, Office of the Actuary, Summary of Other Postemployment Benefits Provided under the New York City Health Benefits Program in Accordance with GASB 74 and 75, for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017 (June 30, 2016), p. 19, www1.nyc.gov/assets/actuary/downloads/pdf/OPEB_Report_FY2017. pdf.

- City of New York, Office of the Actuary, Eleventh Annual Actuarial Valuation of Other Postemployment Benefits Provided Under the New York City Health Benefits Program (June 30, 2015), Appendix B, www1.nyc. gov/assets/actuary/downloads/pdf/OPEB_Report_FY2016.pdf.

- Reimbursement includes the base Part B premium and any additional premium charged to high-income retirees. See: City of New York, Office of the Actuary, Summary of Other Postemployment Benefits Provided under the New York City Health Benefits Program in Accordance with GASB 74 and 75, for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017 (June 30, 2016), p. 7, www1.nyc.gov/assets/actuary/downloads/pdf/OPEB_Re- port_FY2017.pdf.

- City of New York, Office of the Actuary, Summary of Other Postemployment Benefits Provided under the New York City Health Benefits Program in Accordance with GASB 74 and 75, for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017 (June 30, 2016), p. 21, www1.nyc.gov/assets/actuary/downloads/pdf/OPEB_Report_FY2017. pdf.

- Teachers may begin retiring with full benefits at age 55, while City employees in New York City Employees’ Retirement System may not retire until 62 to receive full benefits.

- The average liability presented here reflects only the benefits already earned by retirees and members. If the liability is instead calculated as the present value of expected promised benefits, which would include future benefit increases and employee vesting, the average liability increases to about $247,000 on average.Figure based on 2012 data. See: Center for Retirement Research, How Big a Burden Are State and Local OPEB Benefits? (March 2016), : http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/slp_48.pdf . This figure is based on 2012 data.

- U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Surveys of State and Local Government Finances (September 7, 2017), Table 1: State and Local Government Finance by Level of Government and by State: 2013-2014, https://www2. census.gov/govs/local/15slsstab1a.xlsx.

- To estimate a standard amortization, CBC assumed a 30-year amortization period, with 10 years accounted for in the 2016 liability. We then multiplied the UAAL by 150 percent to account for the remaining estimated 20 of 30 years in the amortization (30/20) to standardize per member estimates.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, A Widening Gap in Cities: Shortfalls in Funding for Pensions and Retiree Health Care (January 2013), http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2013/pewcitypensionsreportpdf.pdf.

- Maria Doulis, Everybody’s Doing It: Health Insurance Premium Sharing by Employees and Retirees in the Public and Private Sectors (Citizens Budget Commission, January 2013), https://cbcny.org/research/everybodys-doing-it.

- Because retirees are able to purchase group health insurance instead of individual policies and because current retirees are able to purchase health insurance at the same price as active (and younger) workers, the cost of the insurance is lower for these retirees.

- City and County of Denver, Colorado, Department of Finance, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of City and Country of Denver, 2016,https://www.denvergov.org/content/dam/denvergov/Portals/344/ documents/CAFR/2016_CAFR.pdf .

- District of Columbia, Office of the Chief Financial Officer, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of District of Columbia, 2016, https://cfo.dc.gov/node/1216356.

- Underwood, et al. v. City of Chicago, No. 13-cv-5687 (N.D. Ill.)

- See: Luke Broadwater, “City plans to stop paying for Medicaid prescription drugs,” The Baltimore Sun (October 24, 2014), www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/politics/blog/bal-city-to-no-longer-pay- for-medicare-prescription-drugs-20141022-story.html.

- Office of the Comptroller, City of San Diego, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year Ended 2012 (November 30, 2012),https://www.sandiego.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/comptroller/pdf/reports/121214cafr2012.pdf .

- ee: Northern Trust, Fixed Income Strategy Municipal Research: Stockton and Detroit Exit Bankruptcy – Key Takeaways (November 2014), www.northerntrust.com/documents/white-papers/asset-management/stockton-detroit-exit-bankruptcy.pdf?bc=23906493.

- This is based on federal employees in the New York City area. Variation exists between different regions for federal employees and retirees.

- The Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, Employer Health Benefits 2016 Annual Survey, http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Employer-Health-Benefits-2016-Annual-Survey.

- The Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, Employer Health Benefits 2016 Annual Survey, http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Employer-Health-Benefits-2016-Annual-Survey

- The Kaiser Family Foundation. Retiree Health Benefits at the Crossroads (April 2014), https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/8576-retiree-health-benefits-at-the-crossroads.pdf.

- Allen Sloan, “General Motors getting eaten alive by a free lunch,” The Washington Post (April 19, 2005), p. E03.

- This estimate is conservative because the actuary report only includes data on current retirees’ spouses and not current workers’ spouses.