A Budget Strategy for Mayor de Blasio's Second Term

Later this week, Mayor Bill de Blasio will release the first budget in his second term—just as the fiscal forecast begins to change. During the first term, a strong city economy produced sizeable tax revenue gains—with tax revenues increasing by $6.3 billion from fiscal years 2014 to 2017—that were used to build reserves and support new mayoral priorities. These sunny days may be nearing an end: the City will have to respond to a troubling federal policy environment, slower economic growth, and State fiscal stress while addressing ongoing expenditure pressures.1

Federal action on tax policy will impact property values, individual tax liabilities, and business activity in ways that are not yet known. Federal spending cuts proposed by the Trump Administration in its first budget and potential federal policy changes, particularly related to public housing, health, and social services, could also place greater demands on the City’s resources. Programmatic spending for new initiatives including expanding pre-kindergarten to 3-year-olds and closing Rikers Island will have to compete with expenses to which the City is already committed, such as debt service, pensions, and retiree health insurance. In fiscal year 2018, 20 percent of the budget, or $18.1 billion, is devoted to these legacy costs.2

This blog presents four strategies to attain and maintain budget stability in the Mayor’s second term:

- Contain spending growth;

- Build reserves;

- Adapt the capital plan to a resource constrained environment; and

- Strengthen finances at public authorities.

Steps in support of these strategies should begin now, and the blog concludes with things to look for in the Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2019 that will indicate how effectively the Mayor is following these strategies.

Four Strategies for Attaining and Maintaining Fiscal Health

1. Contain Spending Growth

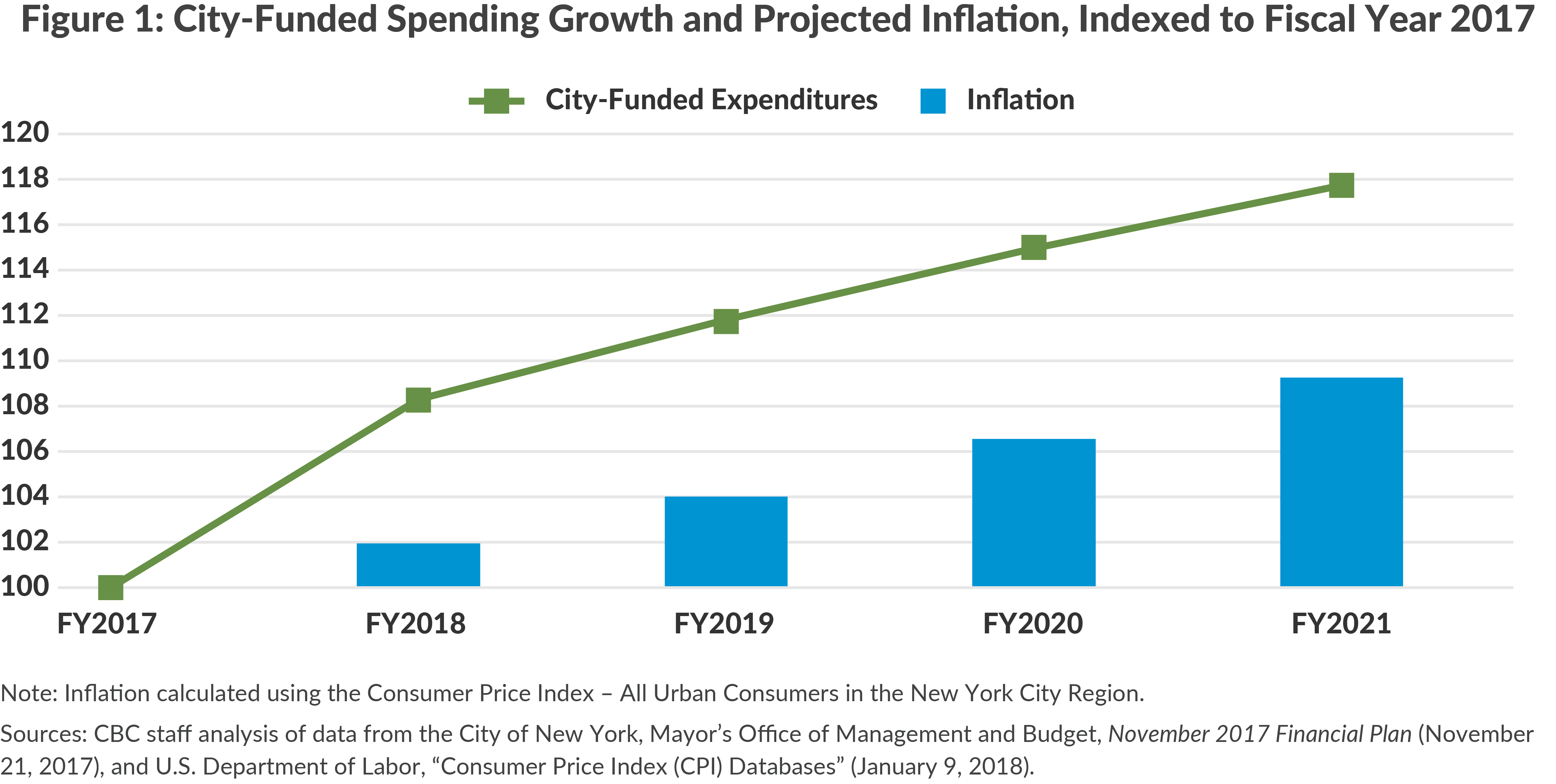

The City continually should strive to deliver services in a cost-effective manner. City-funded spending growth should be kept at inflation, with surplus revenues dedicated to reserves or to paying down long-term liabilities. (See Figure 1.) The cost of new programs should be offset by agency initiatives that generate recurring savings, and the Citywide Savings Program (CSP) should focus on improving the efficiency of operations.

Growth in the City’s workforce, which has reached a record high, should be controlled.3 In addition to the annual cost of salaries and fringe benefits, new employees obligate the City to long-term costs for pensions and retiree health benefits.

For current employees, efforts should be made to contain costs. Overtime for routine and predictable events should be reduced, and caps at the police, fire, and correction departments should be continued and strengthened. The City spent $1.8 billion on overtime in fiscal year 2017, $342 million more than in fiscal year 2014.4

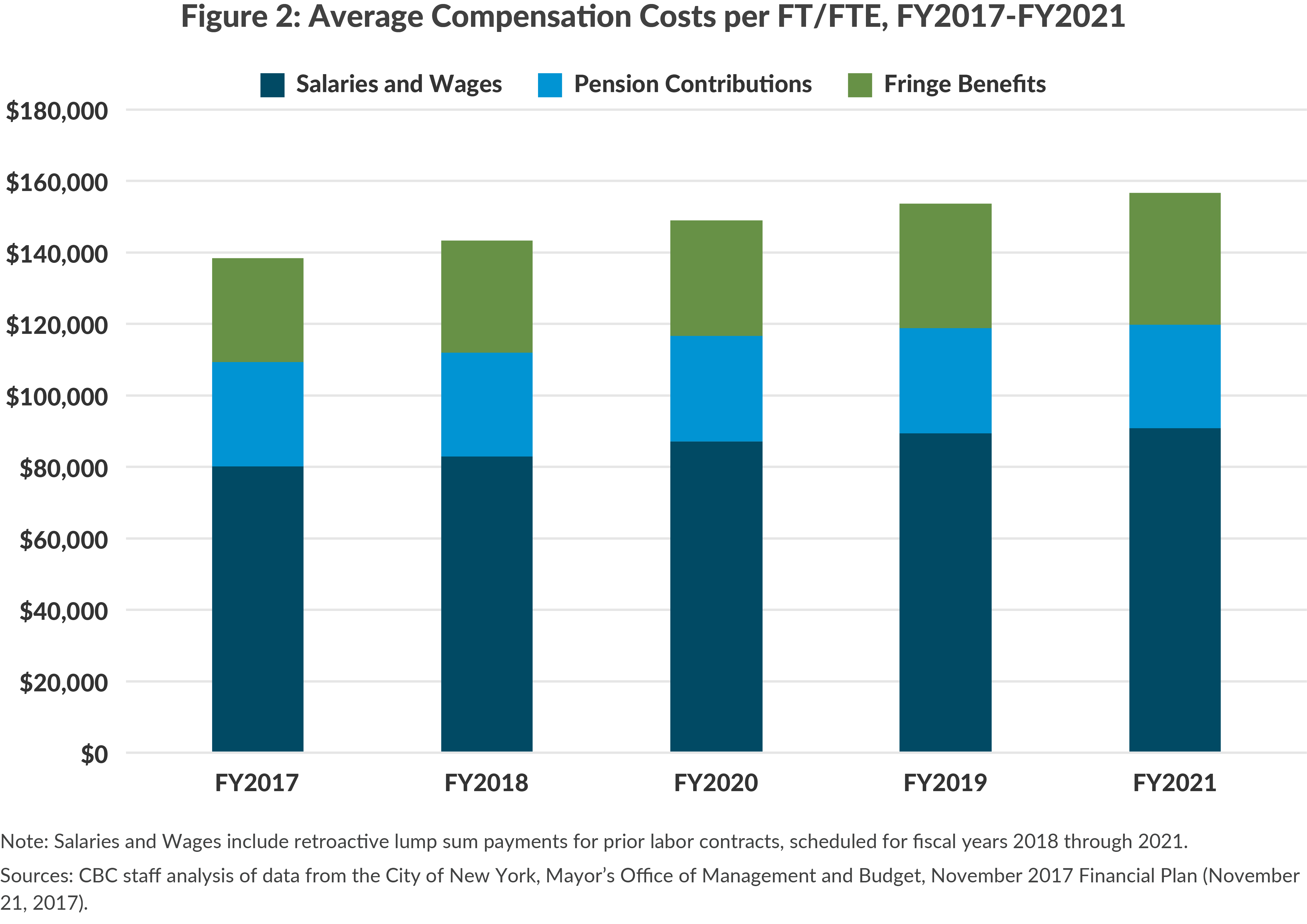

Labor contracts began to expire last summer, and nearly 90 percent of the unionized workforce will be working under an expired contract by the end of calendar year 2018.5 The City has reserved funding for 1 percent wage increases annually and should negotiate labor agreements that reduce financial risk and improve the productivity of the workforce. Compensation costs are projected to grow 3.2 percent each year from fiscal year 2017 to fiscal year 2021, with average compensation per employee growing from $138,000 to $157,000.6 (See Figure 2.)

Salary increases should be funded with savings from work rule changes that improve productivity. In addition, the City should rethink its health insurance arrangements. Building on the success of the first term task force with the Municipal Labor Committee (MLC), the City and the MLC should negotiate savings that target three areas: (1) bending the cost curve in the City’s health insurance plans; (2) improving the administration of the City’s union welfare funds to realize economies of scale in the provision of supplemental benefits; and (3) and reducing the City’s $95 billion liability for retiree health insurance benefits while making regular deposits to the Retiree Health Benefits Trust (RHBT).7

2. Build Reserves

New York City should maintain a budgetary cushion that allows it to cover unexpected revenue or expenditure shocks. The fiscal year 2018 budget includes $1.45 billion in the General and Capital Stabilization Reserves; these reserves stand at $1.2 billion per year in fiscal years 2019 through 2021. The City is projecting budget gaps of $3.2 billion in fiscal year 2019, $2.3 billion in fiscal year 2020, and $1.6 billion in fiscal year 2021.8 If the City were to face another recession, tax revenues could come in between $6.1 billion and $15.8 billion below Office of Management and Budget (OMB) projections over the four-year financial plan, based on experiences during the last three recessions.9

3. Adapt the Capital Plan to a Resource Constrained Environment

The current capital plan calls for $68.6 billion in commitments over the next four years. With the specter of rising interest rates, a delayed federal infrastructure plan, and increasing debt service costs, the City should prioritize projects with identifiable, beneficial impacts, particularly those that bring assets to a state of good repair; new initiatives should be kept to a minimum. The City should use pay-as-you-go capital, improve the capital planning process and management of capital projects to increase efficiency and cost-effectiveness, and lobby the State for design-build authorization and repeal of the Wicks law, both of which would reduce the cost of capital projects.10

4. Strengthen Finances at Public Authorities

The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) and NYC Health + Hospitals (H+H) face substantial and growing fiscal challenges. While these entities have their own financial plans, the City has substantially increased financial support for NYCHA and H+H since fiscal year 2014. The City waived certain reimbursements and assumed the cost of collective bargaining increases and senior centers located in NYCHA developments.11 The net City subsidy to H+H increased from $837 million in fiscal year 2014 to $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2017.12

Declining federal operating subsidies, difficulties increasing rent and non-rent revenues, and high operating costs have caused NYCHA’s fiscal stress. The City should support NYCHA’s efforts to develop new revenue streams and have nonprofit tenants pay rent. Easing work rule restrictions in collective bargaining negotiations and lobbying the federal government to maintain public housing operating and capital subsidies would also stabilize the financial outlook.

The City’s public hospital system is facing declining patient utilization and revenues coupled with shrinking federal support. The City should support efforts to rightsize H+H, even if that means downsizing inpatient capacity. It should lobby the State to alter the Medicaid Supplemental Payments formula so that federal cuts do not disproportionately impact H+H and work with voluntary hospitals to rebalance the provision of care for the uninsured and for behavioral health services.

What to Look for in the Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2019

The Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2019, expected by February 1, should begin to reflect specific state and federal impacts. The following questions can be used to assess whether the City is adequately implementing strategies to address intergovernmental and economic risks.

- Has the City reflected the projected impact of federal tax policy on the national and local economy? How are City revenues expected to be impacted? How will potential changes in state tax policy affect the City and its tax revenues?

- Has the City reflected the projected impact of the New York State Executive Budget, including reductions in state funding for social services, lower than expected state education aid, and increased City funding for the MTA?

- How did the City close the budget gap for fiscal year 2019, currently projected to be $3.2 billion? Is it showing a surplus roll from fiscal year 2018 into fiscal year 2019? What are the sources of those funds?13

- Have the sizes of the General Reserve and the Capital Stabilization Reserve, which totaled $1.25 billion annually beginning in fiscal year 2019, grown?

- Has the CSP grown since November? What are the sources of those savings, and what share is from efficiency initiatives? The CSP included in the November 2017 plan was $1.1 billion over four years, with only 1 percent of savings from improving the efficiency of government.

- How much will the City’s workforce grow? In November total headcount was projected to reach 330,158 positions in fiscal year 2018, an increase of nearly 8,000 positions, or 2.4 percent, from fiscal year 2017.

- Are budgeted levels for overtime, especially at the uniformed agencies, projected to grow?

- How much is in the labor reserve? Currently the City has set aside resources to fund a 1 percent wage increase in each year of the plan.14

- Is there a new health care savings target? The prior savings plan, negotiated by the City and the MLC, was expected to generate $3.4 billion from fiscal year 2015 to fiscal year 2018, with $1.3 billion in recurring savings beginning in fiscal year 2019.15

- How much is the City depositing into the RHBT?

- What is the size of the capital commitment plan, and what share is devoted to state of good repair? The four-year capital plan is currently $68.6 billion with roughly two-thirds dedicated to state of good repair projects.16

- Is the City adding any new subsidies or forms of support for NYCHA, H+H, or the MTA?

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s first term benefited from robust economic growth, but planning for a second term needs to address emerging intergovernmental and economic risks.

Footnotes

- While New York City’s economic growth has been robust and unemployment is low, there are signs of a slowdown. The City added an average 100,000 jobs annually from 2011 to 2016. The City is expected to add 74,000 jobs in 2017 and the Office of Management and Budget projects job growth to decelerate further from 49,100 new jobs in 2018 to 30,800 in 2021. See: City of New York, Independent Budget Office, Disruption Ahead? NYC’s Current Fiscal Outlook Stable, but Federal Tax Overhaul & Budget Cuts Lurk (December 2017), p. 5, www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/disruption-ahead-nycs-current-fiscal-outlook-looks-stable-but-federal-tax-overhaul-and-budget-cuts-lurk-2017.pdf; and Office of the New York State Comptroller, Review of the Financial Plan of the City of New York (December 2017), p. 3, www.osc.state.ny.us/osdc/rpt8-2018.pdf.

- CBC staff analysis of data from the City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, November 2017 Financial Plan (November 21, 2017), www.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/fp11-17.pdf.

- Office of the New York State Comptroller, Review of the Financial Plan of the City of New York (Report 8-2018, December 2017), p. 16, www.osc.state.ny.us/osdc/rpt8-2018.pdf.

- Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the Comptroller for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017 (October 31, 2017), p. 307, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/CAFR2017.pdf, and Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the Comptroller for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2014 (October 31, 2014), p. 300, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/CAFR2014.pdf. >

- Expired contracts include District Council 37, the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, and the Uniformed Firefighters Association. See: City of New York, Independent Budget Office, Disruption Ahead? NYC’s Current Fiscal Outlook Stable, but Federal Tax Overhaul & Budget Cuts Lurk (December 2017), p. 19, www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/disruption-ahead-nycs-current-fiscal-outlook-looks-stable-but-federal-tax-overhaul-and-budget-cuts-lurk-2017.pdf.

- CBC staff analysis of data from the City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, November 2017 Financial Plan (November 21, 2017), www.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/fp11-17.pdf.

- Testimony of Maria Doulis, Vice President, Citizens Budget Commission, before the New York City Council Committee on Finance, Testimony Examining Health Care Savings Under Recent Collective Bargaining Agreements (April 1, 2015), https://cbcny.org/advocacy/testimony-examining-health-care-savings-under-recent-collective-bargaining-agreements; Courtney Wolf and Charles Brecher, Better Benefits From Our Billion Bucks: The Case for Reforming Municipal Welfare Funds (Citizens Budget Commission, August 2010), https://cbcny.org/sites/default/files/REPORT_UWF_08032010.pdf; and Thad Calabrese, The Price of Promises Made: What New York City Should Do About Its $95 Billion OPEB Debt (Citizens Budget Commission, October 25, 2017), https://cbcny.org/research/price-promises-made.

- City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, November 2017 Financial Plan (November 21, 2017), www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/fp11-17.pdf

- The New York City Comptroller recommends a cushion of 12 to 18 percent of total expenditures. This includes the surplus roll, General and Capital Stabilization reserves, bond defeasances, and the balance of the Retiree Health Benefit Trust. See: Office of the New York City Comptroller, Measuring New York City’s Budgetary Cushion: How Much is Needed to Weather the Next Fiscal Storm? (August 2015), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/PARR_Report_Final.pdf; and Michael Dardia and Rachel Bardin, “How Much to Bank on? When it Comes to Revenue Forecasting, Better Safe Than Sorry” Citizens Budget Commission Blog (April 12, 2015), https://cbcny.org/research/how-much-bank-when-it-comes-revenue-forecasting-better-safe-sorry

- Wicks Law is a state regulation that requires several subcontractors to work on a building construction or renovation project worth more than $3 million. The regulation increases project management costs and delays project completion.

- Sean Campion, Room To Breathe: Federal and City Actions Help NYCHA Close Operating Gaps, But More Progress Needed on Implementing NextGenNYCHA (Citizens Budget Commission, July 19, 2017), https://cbcny.org/research/room-breathe.

- Mariana Alexander, Lessons from La La Land: Can the Turnaround of Los Angeles’ Public Hospitals Be Replicated in New York? (Citizens Budget Commission, January 8, 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/lessons-la-la-land

- Under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and State and City law, the City is not permitted to have a surplus or rainy day fund. Instead the City prepays expenses for the following year with current year resources; this prepayment is the surplus roll. For further explanation see: Office of the New York City Comptroller, Measuring New York City’s Budgetary Cushion: How Much is Needed to Weather the Next Fiscal Storm? (August 2015),https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/PARR_Report_Final.pdf

- City of New York, Independent Budget Office, Disruption Ahead? NYC’s Current Fiscal Outlook Stable, but Federal Tax Overhaul & Budget Cuts Lurk (December 2017), p. 5, www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/disruption-ahead-nycs-current-fiscal-outlook-looks-stable-but-federal-tax-overhaul-and-budget-cuts-lurk-2017.pdf

- Testimony of Maria Doulis, Vice President, Citizens Budget Commission, before the New York City Council Committee on Finance, Testimony Examining Health Care Savings Under Recent Collective Bargaining Agreements (April 1, 2015), https://cbcny.org/advocacy/testimony-examining-health-care-savings-under-recent-collective-bargaining-agreements.

- City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2018 Adopted Capital Commitment Plan (November 6, 2017), Vol. 1, p. 8, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/ccp-11-17a.pdf.