How Much, and for What?

These two vital questions about New York City’s capital budget are not being addressed by the mayoral candidates. Although the damage caused by Hurricane Sandy served as a sharp reminder of the importance of public infrastructure and long-term capital planning, Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s Ten-Year Capital Strategy, a plan for $54 billion in infrastructure investments, has received little attention since its release a few weeks ago with the Executive Budget.

Mayor Bloomberg will oversee only the first six months of the Strategy; the next mayor will be responsible for implementing most of the planned investments and revising them to reflect his or her own priorities. In doing so, he or she will have to make difficult trade-offs between competing priorities while ensuring the city’s debt does not become unaffordable.

The Ten-Year Capital Strategy

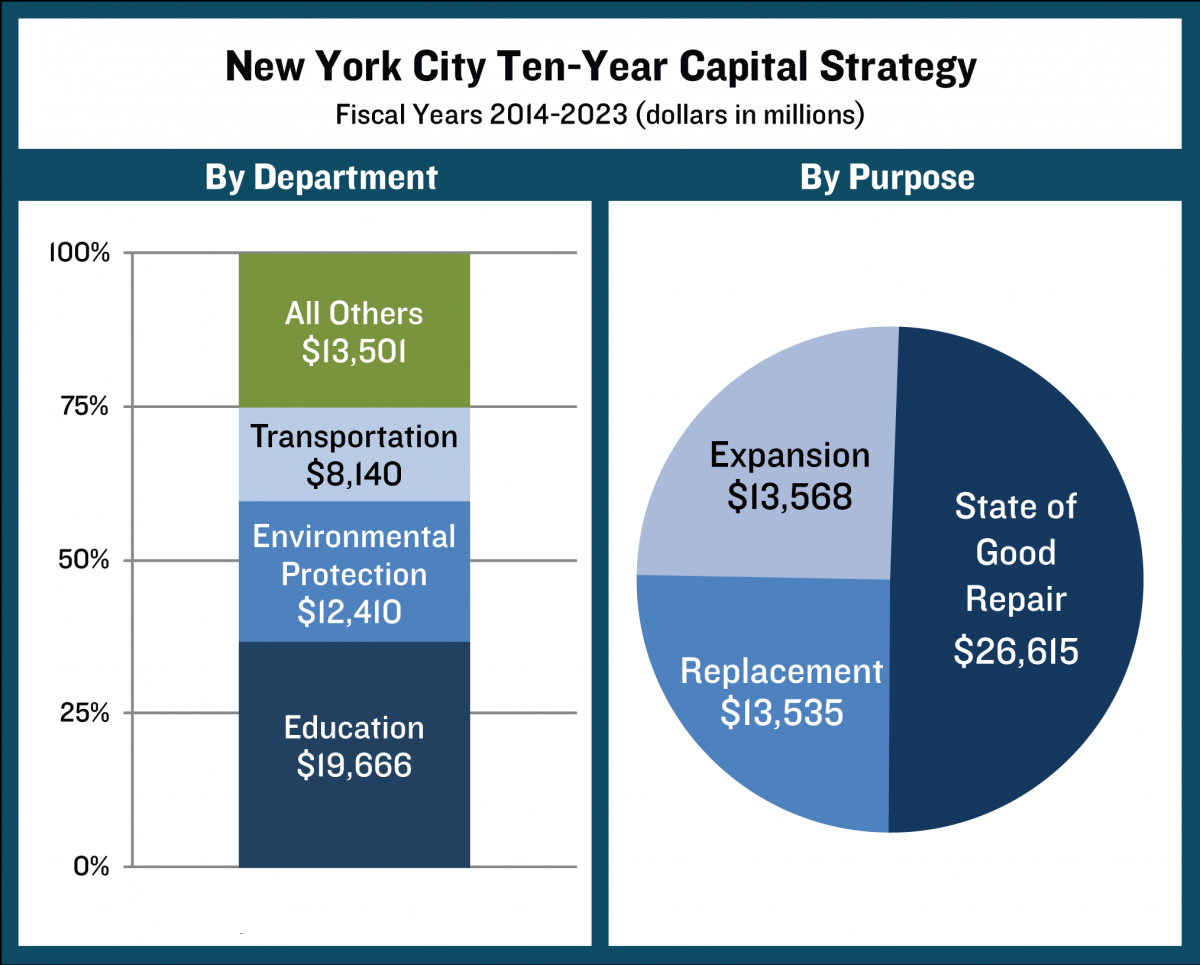

The Ten-Year Capital Strategy is revised every two years; the rolling nature of the plan allows for new initiatives and for unforeseen requirements to become part of the capital planning process. The Strategy for Fiscal Years 2014-2023 is the last time Mayor Bloomberg will articulate his administration’s vision for the long-term capital investments needed to maintain infrastructure, enhance the City’s economy and quality of life, and improve government efficiency. The Strategy proposes $53.7 billion in capital commitments, three-quarters of which are for the three city agencies with the greatest capital assets: the Departments of Education, Environmental Protection, and Transportation.

A capital plan must strike a balance between spending on existing assets and making new investments that can improve services and economic activity. In this plan, half the funding, $24.5 billion, will be devoted to rehabilitating schools, repairing bridges, repaving roads and bringing other assets to what is known as a “state of good repair,” meaning they are fully functional and safe.

A quarter, or $13.5 billion, will be for upgrading equipment and replacing old water and sewer infrastructure and vehicles for sanitation, fire and police services. “Expansion” spending on new assets and large-scale capital improvements will total $13.6 billion, mostly for building new schools, expanding the water and sewer system, and developing housing.

Is this the right mix to meet the city’s needs? The Strategy does not report on state of good repair requirements, but other reports offer some perspective on the adequacy of spending outlined in the Strategy. Agencies have undertaken about half of the necessary repair work each year on average since fiscal year 2003. Persistent funding shortages have resulted in needs that have grown from $4.6 billion in 2003 to $6.4 billion in 2014.[1] The fiscal year 2014 report shows 58 percent of required state of good repair work will be funded— indicating the spending devoted to this purpose in the Ten-Year Strategy is insufficient.

Also unaddressed in the Strategy is the need to make the city more resilient in the face of threats from climate change. The Economic Development Corporation (EDC) will make recommendations to guide and enhance future resiliency efforts later this month. These proposals will need to be incorporated into the city’s long-term capital agenda, and could have a significant price tag attached to them.

The Debt Burden

Unmet needs cannot be addressed by simply expanding the size of the capital plan. The City borrows funds to pay for its capital projects, and the long-term capital plan must be devised with an eye toward debt affordability. The City has a constitutional debt limit that is not in danger of being breached,[2] but the debt burden is high and growing according to metrics used by the credit rating agencies.

Debt outstanding

The City finances its capital program with three types of bonds: general obligation bonds, backed by the full faith and credit of the City; bonds issued by the Transitional Finance Authority, which are backed by the personal income tax; and bonds, repaid with user fees, issued by the Municipal Water Finance Authority to improve the water and sewer system. The city also has “conduit debt” from bonds sold on behalf of other entities and debt from securitization of revenues from tobacco settlements. Water Authority bonds, which are not legally debt of New York City and are not repaid from the city budget, are excluded from this analysis.

In fiscal year 2013, city debt outstanding totaled $67.9 billion ($96 billion including the Water Authority), up 45 percent since 2003. Debt is projected to grow by an additional 11 percent to $75.5 billion by fiscal year 2017. (Projections to the end of the Ten-Year Capital Strategy are not available.)

Affordability of debt is determined in relation to the adequacy of resources available to repay it. Two ratios are commonly used, and City debt is high according to both. One measure is debt outstanding as a share of the full value of the property tax base; a value greater than 5 percent is considered “above average.”[3] The ratio for the City is 8.1 percent in fiscal year 2013.[4] An alternative measure is relative to personal income; a ratio greater than 6 percent is considered to be high.[5] The ratio for the City is 14 percent in fiscal year 2013.[6]

Debt service

The City pays the principal and interest on bonds, known as debt service, from its operating budget. High and growing debt service costs reduce resources available for other priorities, restrict flexibility to manage operating expenses, and limit the ability to undertake additional capital investments.

City debt service has been rising at a rapid rate, growing 6.3 percent annually on average between fiscal years 2003 and 2013. It is projected to grow by an additional 30 percent, from $6.1 billion to $7.8 billion, by fiscal year 2017.

The affordability of debt service is examined with respect to the share of spending: more than 12 percent of general fund spending is regarded as above average and more than 15 percent as high.[7] Debt service currently makes up 14.6 percent of city-funded expenditures and will rise to 17 percent by fiscal year 2017.[8]

Challenge for the Next Mayor

The last two mayors have considered specific debt metrics to guide capital investments. In 2001, the Giuliani Administration issued a formal statement of debt policy that defined an affordable debt burden as one for which debt service does not exceed 20 percent of city tax revenues.[9] The Bloomberg Administration kept capital spending proposals to a level such that the city’s debt service would be near 15 percent of total city tax revenues.

The next Mayor will have to determine a level of long-term capital investment that takes into account the city’s already high debt burden. The economic forecasts and political climate do not warrant optimism that increased funding from Albany or Washington will be available for New York City capital projects; city taxpayers will continue to pay for most infrastructure. While greater investment would be worthwhile to fix and renovate city assets and infrastructure, as well as to address the need to make the city more resilient in preparation for future storms, difficult trade-offs will have to be made among these priorities and others to keep debt from becoming unaffordable.

Footnotes

- Four-year estimates as reported in the Asset Information Management System (AIMS). City agencies that manage critical infrastructure—bridges, schools, public housing, and the water and sewer system—perform detailed inspections of the safety and condition of their assets. Most other agencies report on the work needed to bring assets to a state of good repair in AIMS. The report excludes smaller assets, like the equipment used by city agencies, and most or all spending required for the large-scale infrastructure mentioned; therefore, the estimate in AIMS is best interpreted as the minimum spending required.

- General obligation debt outstanding is limited to 10 percent of the average of the full value of taxable real property in the previous five years; it is currently around five percent. The city ran close to its debt limit in the 1990s, prompting the creation of the Transitional Finance Authority (TFA). TFA debt is limited to $13.5 billion in outstanding bonds, although the City has authority to issue bonds over the $13.5 billion limit provided that the excess, together with the amount of indebtedness contracted by the City, does not exceed the constitutional debt limit.

- Fitch Ratings, “U.S. Local Government Tax-Supported Rating Criteria,” August 14, 2012, pg. 8. See also Fitch’s discussion of the city’s “high debt burden” in its rating of the City’s GO bonds in Business Wire, “Fitch rates New York City’s GOs ‘AA’,” February 22, 2013, accessed February 23, 2013, www.businesswire.com/news/home/20130222005858/en/Fitch-Rates-York-City-NYs-GOs-AA.

- Calculated using debt outstanding for GO, TFA, TSASC and conduit debt, as reported in the Executive Budget for FY2014, and full market value of all taxable real property in fiscal year 2013 as reported in the FY2013 Property Tax Fixing Resolution.

- Standard and Poor’s public finance ratings criteria as reported by New York City Comptroller, “Fiscal Year 2013 Annual Report on Capital Debt and Obligations,” December 2012, pg. 25. See also Standard and Poor’s, “RatingsDirect: New York City; General Obligation,” February 25, 2013, accessed April 29, 2013, www.comptroller.nyc.gov/bureaus/pf/pdf/ratings-reports/SP-Report-NYC-GO-2013-F1F2GH-FRN-Reoffering.pdf.

- Personal income as reported in the Executive Budget for FY2014.

- According to Fitch and S&P criteria, respectively.

- City-funded expenditures include $1 billion from the Retiree Health Benefits Trust Fund; figures net of impact of prepayments in FY2013.

- New York City Office of Management and Budget, Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2002 Message of the Mayor, “Mayor’s New Annual Statement of Debt Policy,” pgs. 109-114.