Amend it, Don’t End It

Improve 421-a to Spur Rental and Affordable Housing Development

New York City’s 421-a property tax exemption is slated to expire in June 2022. This incentive has been essential for production of both market-rate and affordable rental housing in New York City. Due to high construction and operating costs, the largest being the property tax, nearly all rental development in New York City is not financially feasible without government assistance. While flawed, the as-of-right 421-a tax exemption effectively reduces operating costs and makes it possible to build rental housing.

Allowing 421-a to lapse would significantly reduce rental housing development, worsen the city’s existing housing supply shortage, and make New York City’s already scarce and costly rental housing scarcer and more expensive. New York City does not produce enough housing, even with the 421-a program in place. Without the 421-a program, housing production rates would fall even further than their already low levels.

Until State lawmakers pass a broad reform package that successfully reforms the property tax system to reduce the tax burden on multifamily rentals, reduces construction costs, and modernizes other laws and regulations that now increase operating costs, the need for an incentive will remain. State lawmakers should authorize an as-of-right tax exemption designed to foster rental housing development, minimize disruption of land and development markets, and help the City meet its affordable housing production goals.

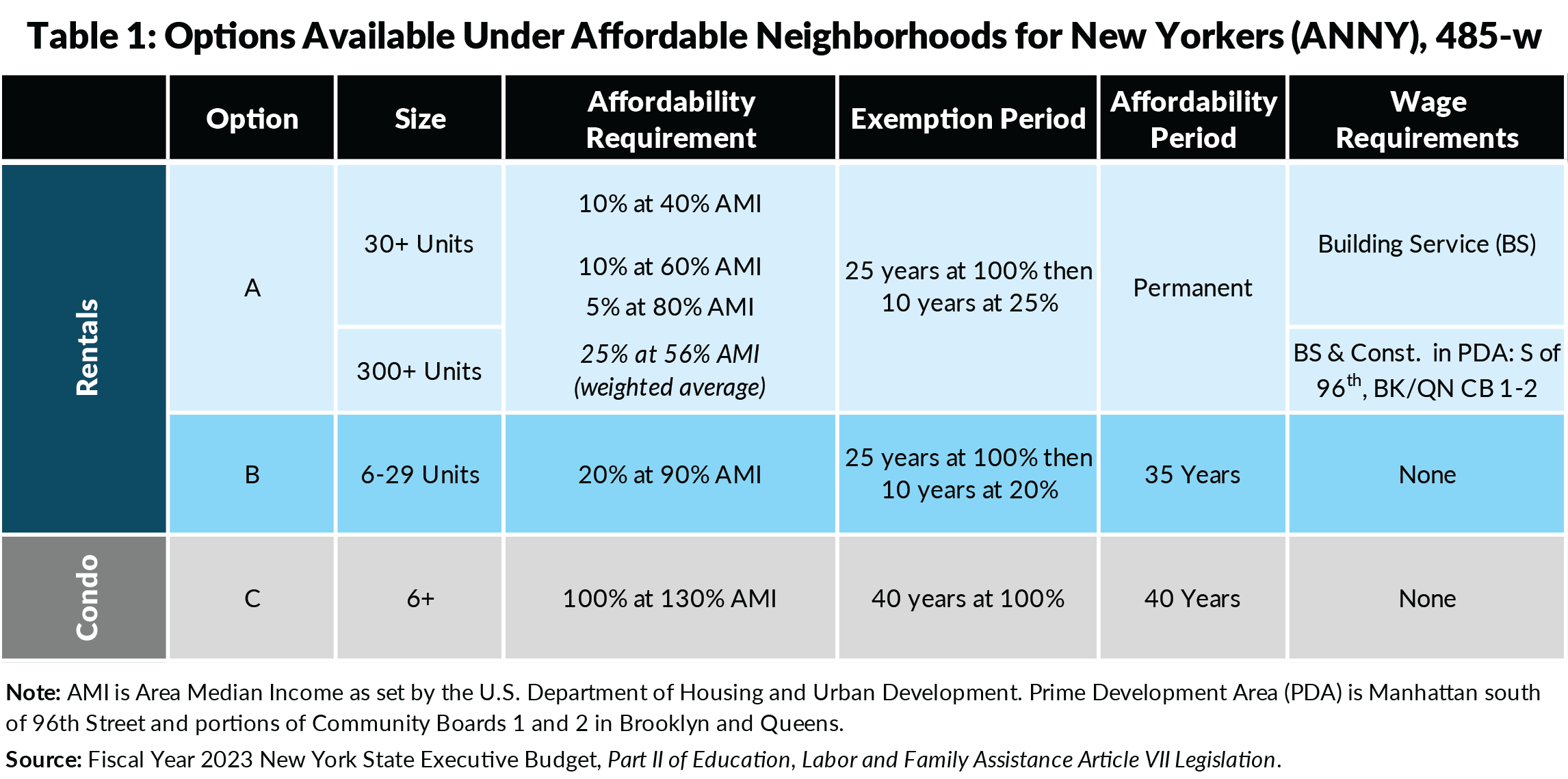

Governor Kathy Hochul’s Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2023 proposed to replace 421-a with 485-w, the Affordable Neighborhoods for New Yorkers program (ANNY). ANNY would simplify the program, deepen the levels of affordability, and slightly reduce the total amount of foregone revenue under the tax expenditure.

CBC’s analysis of the proposed ANNY program and its impact on typical rental housing developments found that:

- Allowing 421-a to lapse with no successor would suppress rental housing development;

- ANNY would produce more housing than if 421-a were to lapse, but likely would yield less housing development than under the current version of the program;

- ANNY’s incentives would be less generous than 421-a but still sufficient to develop two types of rental buildings: small rental buildings of 29 or fewer units; and large rental buildings in neighborhoods that command the highest rents;

- Most buildings with 30 or more units in moderate- and middle-income neighborhoods would not be viable under ANNY because rents are not high enough to subsidize a large share of deeply affordable units; and

- ANNY may make it harder for the City to increase development through upzonings, particularly outside the Manhattan core, if it reduces the financial viability of the rental buildings most likely to be built in rezoned neighborhoods.

CBC recommends the following changes to improve ANNY:

- Modify ANNY to increase the amount of affordable and market rate rental development. ANNY’s deep affordability options are viable only in neighborhoods that support very high market-rate rents. In most moderate- to middle-income neighborhoods, market-rate rents are not high enough to cross subsidize deeply affordable units. Modifying ANNY to accommodate market conditions in these moderate to middle-income neighborhoods could yield more production. Two options to do so include: 1) offering an additional option for rental buildings of 30 or more units outside of the Manhattan core and waterfront neighborhoods that reflects these areas’ lower market rents and lower ability to cross subsidize below-market rent units, or 2) expanding the proposed levels and shares of affordability for smaller buildings of 6 to 29 units to more types of development.

- Ensure greater transparency and public reporting of data to support a robust assessment of the program’s impact and effectiveness, which would inform any successor program. The City should collect and publicly report additional data on the projects that use ANNY, including the number and affordability levels of units produced as well as tax assessment data; summary data on development trends by community district to put ANNY development in a proper context; and improved reporting on “pipeline” projects currently in construction that anticipate applying for ANNY benefits.

- Harmonize the City and State affordable housing programs and reduce bureaucratic conflicts and red tape. Better alignment between ANNY’s affordability requirements and the City’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) program would yield more development and speed up the development process. The ANNY bill language should also clarify how the program would be available to projects receiving tax exempt bonds or City capital subsidies.

Property Tax Exemptions are Effective at Spurring Rental Housing Development

The combination of high construction costs and very high operating costs (including property taxes) makes it so expensive to build rental housing in New York City that nearly all new multifamily rental development requires some form of subsidy to be financially feasible. This high-cost environment also makes it difficult to build rental housing at rents that New Yorkers can afford, even with tax breaks.

Rental developers in New York City face construction costs that are among the highest in world. Turner & Townsend’s annual construction cost surveys indicate that New York’s construction costs are a third more than European cities like Paris and more than double Toronto’s.1 In the US, New York’s construction costs are comparable to San Francisco but 10 percent higher than Los Angeles, over 40 percent higher than Chicago, and double those of Houston. New York City’s construction costs historically have also increased faster than the overall rate of inflation (averaging 3.7 percent annually since 2010) and are currently experiencing higher-than-usual inflation pressures. Costs increased 8 percent between February 2021 and February 2022.2

Operating costs for multifamily rentals are also higher in New York City than the national average. Survey data on operating expenses compiled by the National Apartment Association, compared to data reported by property owners to the City’s Department of Finance, suggest that the cost to operate a multifamily building in New York City is 50 percent higher than the national average. Fully taxed rental buildings in New York report spending between 60 and 65 percent of gross rental income on expenses as compared to an average of 38 percent elsewhere in the country.3

In New York City, the high property tax burden on multifamily rentals—particularly as compared to the lower effective tax rate on homeowners—is a commonly cited factor driving up operating costs. As a percentage of rental income, New York’s property taxes are high: 30 percent in New York City compared to 13 percent elsewhere in the country. Other components of property management costs also are more expensive in New York City.4

Since property taxes are a rental building’s largest expense and one that government controls, tax exemptions are an effective way to spur development. Exempting new rental development from property taxes makes many projects feasible that otherwise would not get built. For rental buildings in New York City, a 100 percent property tax exemption conservatively reduces operating expenses, excluding debt service, from about 60 to 65 percent of gross rental income to 30 percent of income, depending on a building’s size; this brings expenses as a percentage of income roughly in line with national averages.5

This reduction in costs makes it possible to finance a new construction project while charging rents that some prospective tenants are able to pay, although often still at levels beyond what many New York City households can afford.

Incentivizing Affordable Rental Housing Development through 421-a

The 421-a tax exemption has evolved into an affordable housing development program over time. When originally created in the 1970s, the program had no affordability requirements and was intended to spur housing production in the city. Over time, affordable housing requirements have been added, removed, and modified.

More recent iterations of the program have required deeper levels of affordability in Manhattan and some areas of Brooklyn and Queens; these requirements aim to generate units at deep discounts to market-rate rents in high opportunity neighborhoods without the need for discretionary City capital subsidies. Outside of the strongest markets, however, market-rate rents are not high enough to subsidize a significant share of deeply affordable units, and in many cases, the tax exemption is necessary simply to stimulate market-rate production.6 Under the most recent version of the 421-a program, State law required these rental projects to set aside moderate or middle-income units in exchange for receiving 421-a benefits. While these middle-income units often rent at or near market-rate prices, the affordability restrictions serve as a bulwark against future appreciation and neighborhood change.

Governor’s Proposed 421-a Replacement

The New York State Fiscal Year 2023 Executive Budget proposed to replace 421-a with ANNY, in section 485-w of the Real Property Tax Law. (See Table 1.) ANNY would retain the basic structure and intent of the current 421-a program but simplify it, deepen the level of affordability required to receive the tax break, and modestly reduce the total lifetime cost of the tax expenditure. Specifically, compared to 421-a, ANNY:

- Simplifies: ANNY would have three options, two for rental housing and one for affordable homeownership, that apply to all projects citywide. This is fewer than the seven options in 421-a that vary by geography and size of a project.

ANNY Option A would apply to all rental projects of 30 or more units regardless of location. Option B would apply to all projects with between 6 and 29 units. Option C would be a means-tested homeownership program.

- Deepens affordability: ANNY would require developers to set aside units at deeper levels of affordability than under the current program and would eliminate the option to set aside units at middle-income levels.7

Under ANNY, affordable income bands would top out at 80 percent of Area Median Income (AMI) in Option A with a weighted average of 56 percent of AMI, or 90 percent of AMI in Option B. Under the current program, projects located south of 96th Street in Manhattan and some projects with 300 or more units are able to set aside units at an overall weighted average of 66 percent of AMI, including no more than 5 percent at middle income levels (120 to 130 percent of AMI depending on location); elsewhere, developers can set aside 30 percent of units at 130 percent of AMI.

Under ANNY, affordable units built in projects of 30 or more units would also be required to be permanently affordable, while those in smaller buildings would be affordable for 35 years and remain rent stabilized after. Currently, all income-restricted 421-a rental units revert to free-market status upon the first vacancy after the 35-year affordability period expires.

- Lowers total lifetime tax expenditure: ANNY proposes to phase out the tax expenditure for the largest rental projects, reducing the amount of foregone revenue. ANNY would limit the full 100 percent exemption period to 25 years for all rental projects, followed by an additional 10 years at either 20 or 25 percent of assessed value. Under the current program, buildings of 300 or more units in core areas can secure 100 percent exemptions for the full 35-year period.

The other provisions of ANNY would mirror those in 421-a, including average site-wide wage requirements for construction workers of buildings of 300 or more units in an area referred to as the Prime Development Area (PDA), which is comprised of Manhattan south of 96th Street and portions of Community Boards 1 and 2 in Brooklyn and Queens. (Some affordable housing projects are exempt.) It also would retain the requirement that buildings of 30 or more units pay prevailing wages to building service workers.

Impact of ANNY on Rental Housing Development Varies by Location and Type of Project

Study’s Methodological Approach

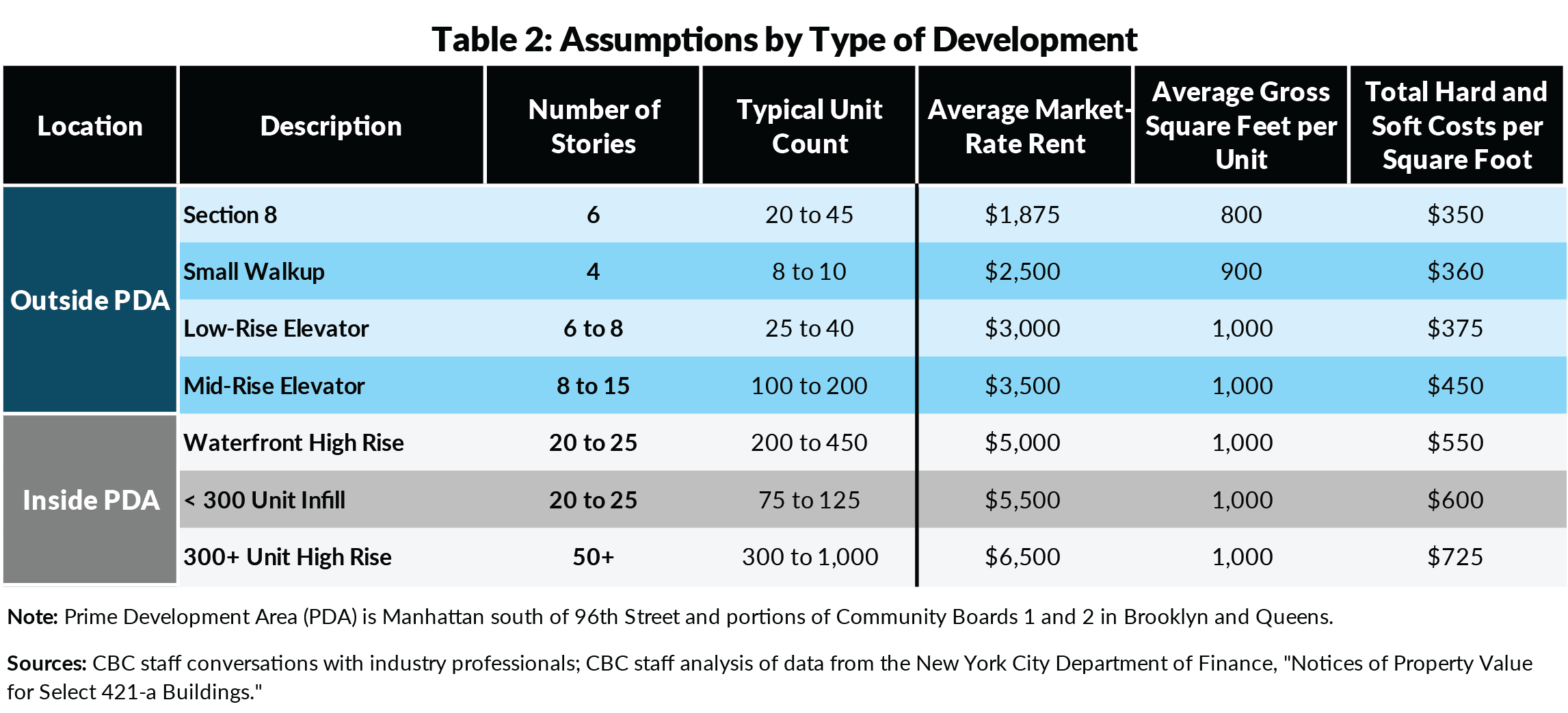

This policy brief models the financial feasibility of seven types of rental buildings that are commonly built through the 421-a program using a methodology similar to that used in the City’s MIH financial feasibility study.8 The analysis determines whether a 421-a property tax exemption is necessary to make development possible and assesses how the changes in affordability levels and shares proposed under ANNY would affect projects in different ways, as well as the magnitude of those changes. Every project’s cost and rents are unique; these projects represent typical projects and are not based on specific buildings. Individual buildings may be more or less viable than these examples depending on their specific characteristics.

Table 2 presents the seven prototypical 421-a projects and key assumptions for each. Four projects are typical of rental development in the outer boroughs and upper Manhattan, outside what ANNY refers to as the PDA:

- Small buildings built primarily in the Bronx designed to rent at prices pegged to Section 8 rental housing voucher program;

- Small 8- to 10-unit walkup buildings without parking;

- Low-rise elevator buildings with limited on-site amenities and fewer full-time building service workers; and

- Full service, mid-rise elevator buildings.

The remaining three are rental projects typically built within the PDA:

- Mid- to high-rises typically built along the Brooklyn and Queens waterfronts;

- Rental buildings with fewer than 300 units, typically built on smaller lots; and

- 300+ unit high rise towers built on larger sites.

The analysis makes assumptions about the average rent, unit size, and construction costs of each of the seven illustrative projects.9 Assumptions about expenses as a share of gross income are constant across the seven projects: 60 percent without a tax exemption and 30 percent with one. Affordable rents are based on 2021 rent limits published by the Department of Housing Preservation and Development.10

Feasibility Metric

This study uses the Yield-on-Cost (YOC) metric to measure financial feasibility. YOC is a measure of annual return on investment, calculated by dividing a project’s net operating income in its first stabilized year of operations by the total cost to develop the project, including land. (Net operating income is a project’s actual rental income minus operating expenses but before income taxes, debt service, and profit.) YOC is intended to measure a project’s basic feasibility without having to make additional assumptions about how the project is financed or about future trends in rents, expenses, or interest rates. For the purposes of this analysis, a five percent YOC is considered the minimum return necessary for a development to proceed; this is a conservative rate of return that reflects both the risks of new development and current market conditions.11

Land Prices

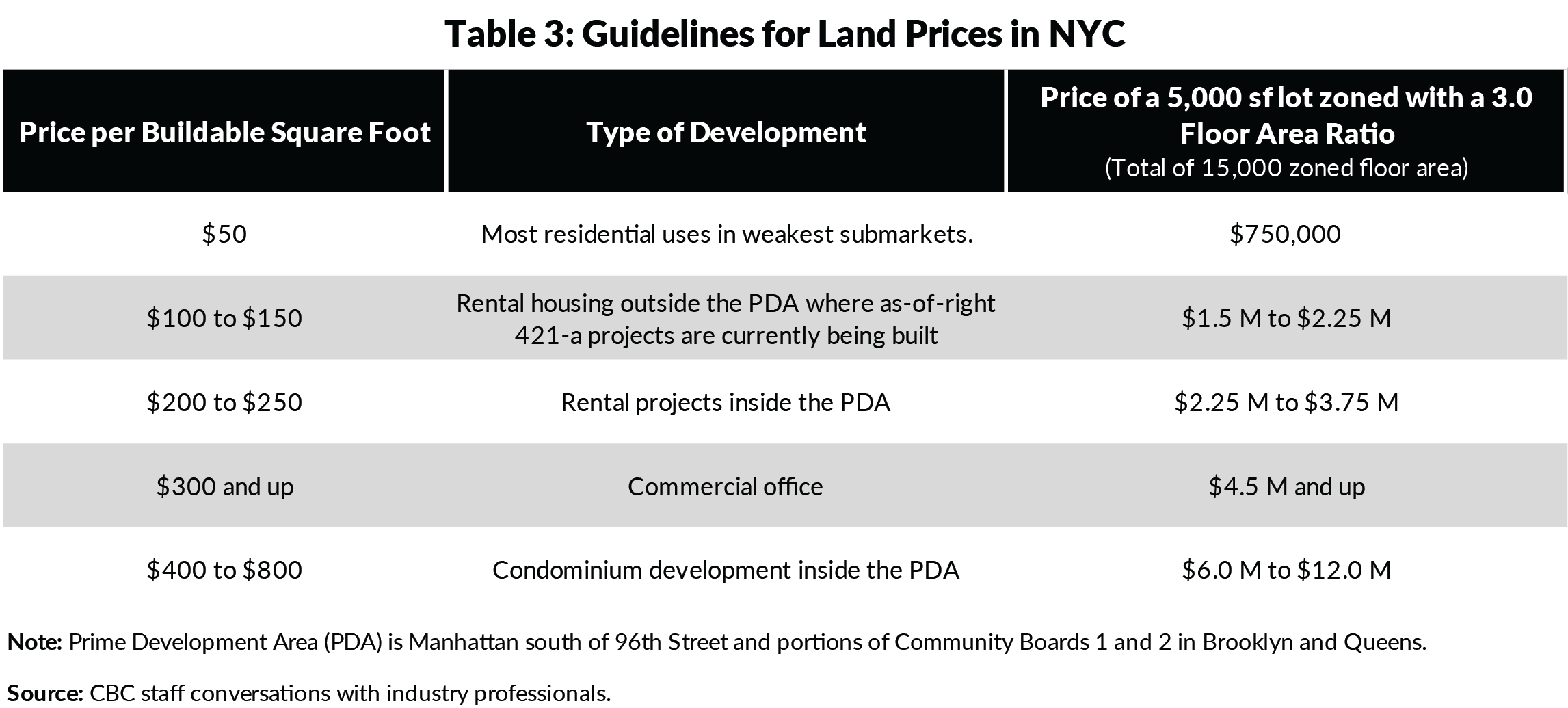

This study analyzes land prices based on the potential price per buildable square foot that a developer is willing to pay given a set of assumptions about rents, operating costs, construction costs, and the size and design of a building. Table 3 provides guidelines for land prices in different areas of the city for different potential uses based on conversations with industry professionals active in land development.

How Land Prices Affect Development Feasibility

Land prices vary widely throughout the city and depend on several factors, including a property’s current use value or income streams; how much density is allowed under zoning; which uses are allowed as of right; whether additional discretionary approvals are required; whether the site requires demolition or environmental remediation; and a developer’s expectations about future rents/sales prices and construction costs. Traditionally, developers view land as a “residual” – meaning that they back into what they are willing to pay for land based on their assumptions about the factors listed above and the minimum amount of profit they would accept. If the residual land value is lower than the current asking price for land, the development will not move ahead.

In general, the more lucrative a potential project, the more a developer is willing to pay for land. For any given site, holding density constant, a condo developer is typically willing to pay more for development rights than a developer looking to build commercial office space, who in turn is willing to pay more than a developer looking to build rental housing.

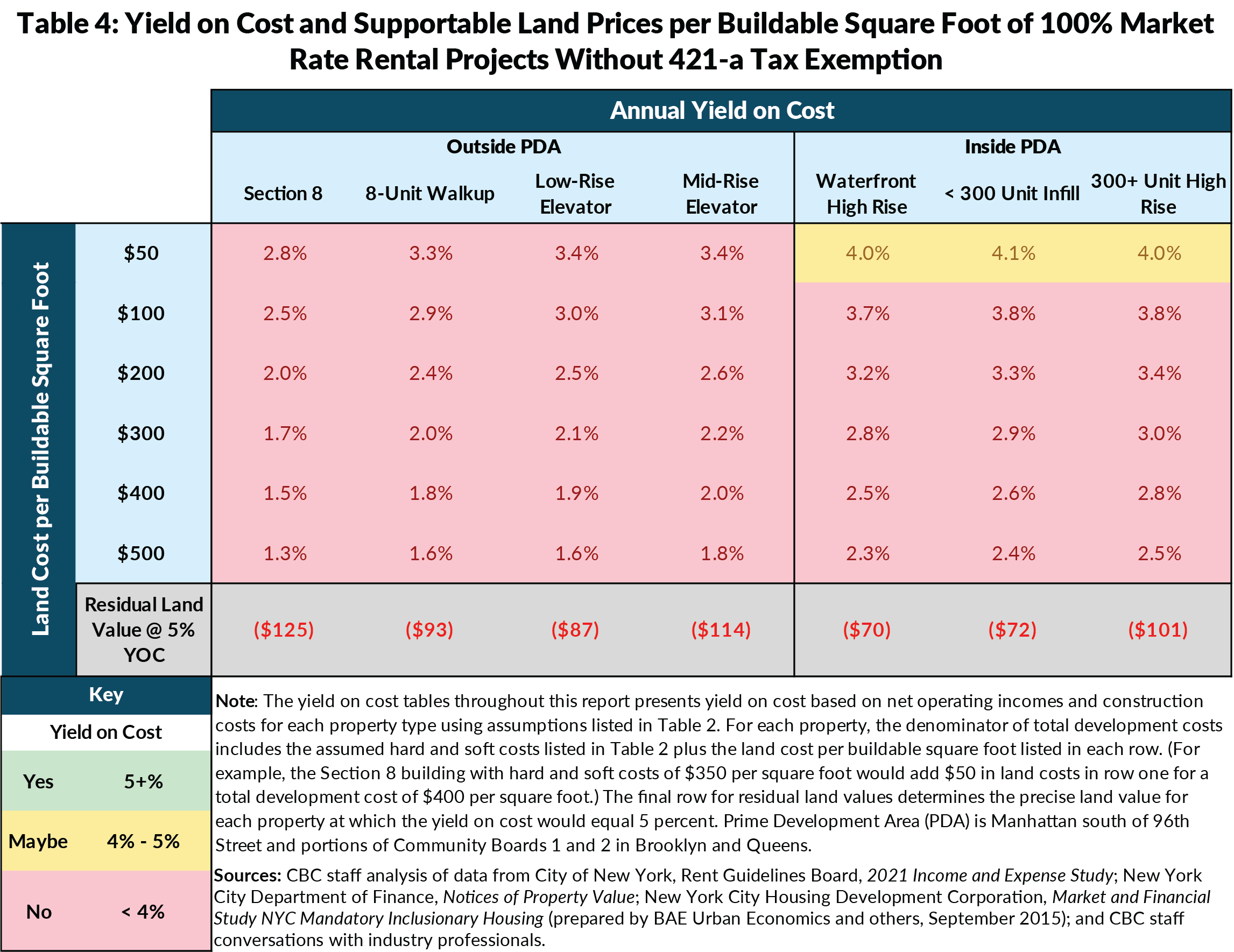

Allowing 421-a to Lapse Would Suppress Rental Housing Development

Without a property tax exemption, none of the seven rental projects would get built as rental housing.12 The projects would not generate a sufficient return on investment—a YOC equal to or greater than 5 percent—that would make most developers willing to take on the risk of building the project. (See Table 4.)

For all seven projects, net operating incomes and YOC would be too low to justify new development, even if land were free. The residual land value row in Table 4 shows the price per buildable square foot that would achieve a five percent YOC. Across all seven typical rental developments, the YOC is below five percent at land costs ranging from $50 per square foot to $500 per square foot. In fact, potential net operating incomes would be so low at current rents that they would only generate a 5 percent YOC with land prices that are negative.

Thus, without 421-a, rental housing development would require both free land and an additional upfront subsidy for most developers to take on the risk of building. This suggests that even if land prices were to fall following the elimination of 421-a, that decrease would not make most development projects feasible, and that rental projects would only get built if developers were willing to accept very low returns on investment.

Instead, most potential rental development sites either would not be developed or would be built as something other than rental housing. Depending on the site and the zoning, developers may opt to build condominiums or other commercial projects if those are viable options. In other cases, current landowners may prefer not to sell if the value of the land for development is less than the use value or income stream it currently generates.

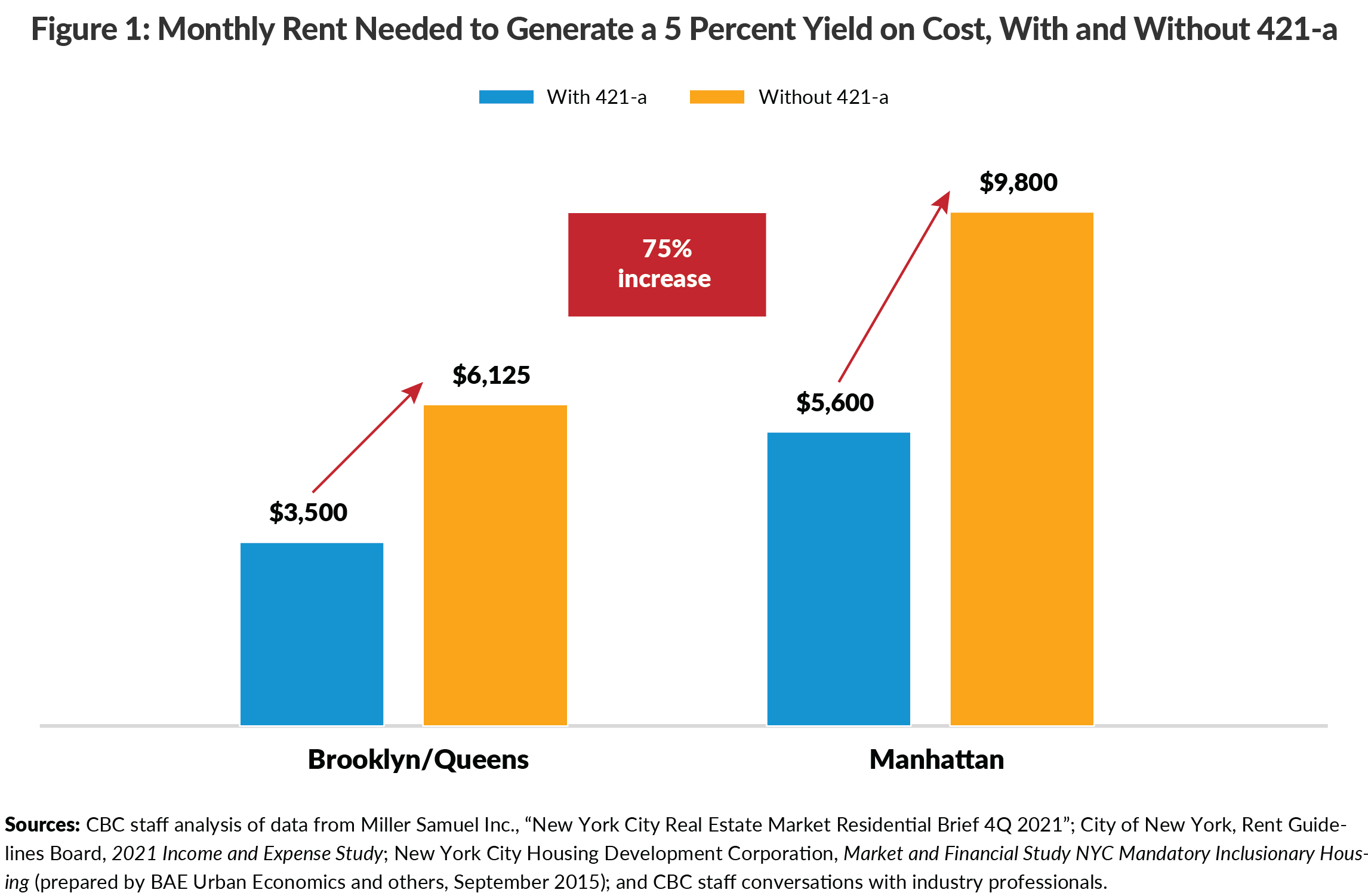

Evaluated from a different perspective, without the exemption, rents would have to increase by 75 percent to generate a reasonable rate of return, holding other costs constant. For the typical new development project in Brooklyn and portions of Queens, rents would need to increase from about $3,500 per month (the approximate median rent for new development projects) to over $6,000 to produce a 5 percent YOC, while the median Manhattan rent would have to increase from $5,600 to $9,800.13 (See Figure 1.) Given that rents are unlikely to rise to those levels, the amount that developers could pay for potential development sites would fall below market prices, and these rental developments would not be built.

ANNY Would Incentivize Rental Development, but at Lower Levels than the Current Program

Under ANNY, the deeper affordability requirements would reduce net operating income for all seven rental projects compared to the current program and could reduce profitability if other costs remain constant. The scale of those impacts, however, varies significantly by neighborhood and project size, and, in general, are largest in moderate- to middle-income neighborhoods outside the PDA.

The Deep Affordability of Option A is Viable Only in High-Rent PDA Neighborhoods

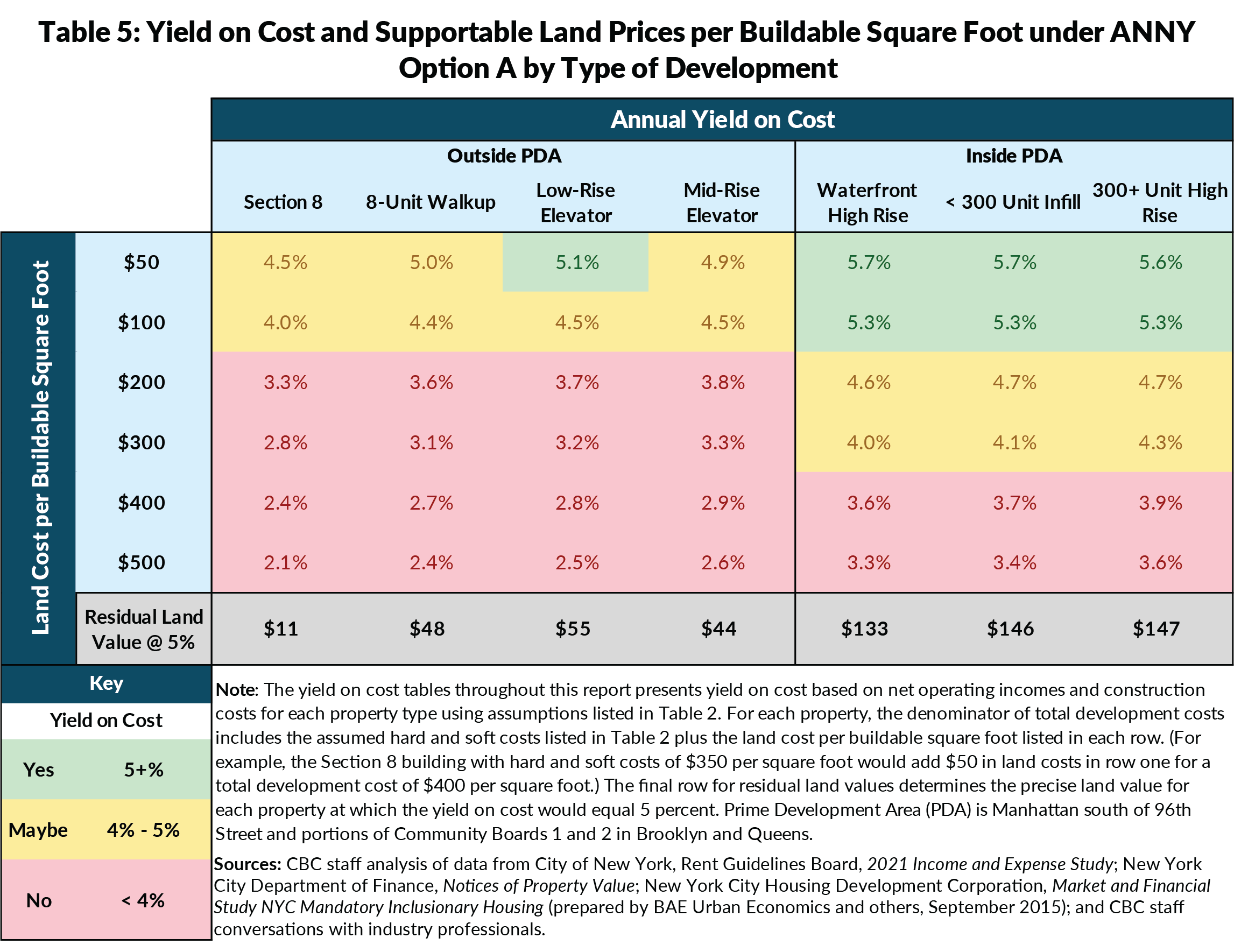

The deep levels and shares of affordability required under Option A—a weighted average of 25 percent of units at 56 percent of AMI—are viable only in neighborhoods where renters will pay very high market-rate rents.

Table 5 shows the YOC for the seven projects if they were built under Option A at different land values. Option A would be financially feasible only for projects inside the PDA, all of which can support market-rate rents of $5,000 or more per month. (See Table 2 for rent assumptions for each of the typologies.)

By contrast, none of the four examples of development in moderate to middle-income neighborhoods located outside the PDA would be feasible. In these neighborhoods, market-rate rents generally are not high enough to generate a sufficient return on investment given the deeply affordable rents required under ANNY Option A, even with a property tax exemption. Setting aside 25 percent of their units at 56 percent of AMI would reduce their net operating incomes by 15 percent compared to the 130 percent AMI option offered under the current version of 421-a, assuming market-rate rents remain constant. That significant decrease in operating income would render many of these projects financially infeasible at current land prices.

At a 5 percent YOC, land prices for potential development sites in these areas would fall below $50 per buildable square foot, which is below the floor price that landowners would accept for even the least expensive residentially zoned land in the city. Development would be feasible on sites outside the PDA only if projects have below-market land costs, smaller-than-average unit sizes, and less expensive construction options, or if developers are willing to accept lower returns on investment.

Projects inside the PDA would be viable at land prices of $130 to $200 per buildable square foot, depending on a developer’s return expectations and development assumptions. This is less than what some developers would pay under the current program, but still potentially feasible. This suggests that projects that work under the current 421-a program likely would work under the new program, potentially with changes to reduce costs or generate additional income, such as building smaller units that generate higher rents per square foot.

Projects located south of 96th Street in Manhattan are less affected by the decision to deepen affordability because they already rent at high enough prices to cross subsidize affordable units; in fact, many of these projects are already required to meet deep affordability targets under the current version of 421-a (25 percent of units at 66 percent of AMI currently compared to 25 percent at 56 percent under ANNY).

Two caveats may make our conclusions about development inside the PDA optimistic.

First, feasibility is not the only factor that determines whether a project gets built. The residual land values shown in Table 5 are sufficient to support land acquisition and development in some neighborhoods within the PDA, but if other types of development like condominiums are willing to pay more, those bids will win out. Even if a rental development is theoretically feasible, if rental housing is not the most profitable potential use of a property, it will not get developed as rental housing. In fact, many potential rental developments in Manhattan already are being outbid by condominium developers under the current 421-a program.

Second, this analysis does not capture the impact of the reduction of the tax exemption in Years 26-35 for 300-plus-unit projects or of the permanent affordability requirement on rental buildings of 30 or more units. The YOC feasibility metric used in this analysis relies on potential returns in a single stabilized year of operations; it does not reflect the value of changes in income or expenses over time. (Other metrics that incorporate the time value of money, such as discounted cash flows or internal rates or return, would better capture the impact of these changes.) In general, however, both policies would only reduce profitability. Depending on the magnitude of those impacts, the combination of a shorter exemption period and permanent affordability could affect some investment decisions or financing options; change the mix of developers who are willing to build rental housing; or make landowners less willing to sell land to rental developers.

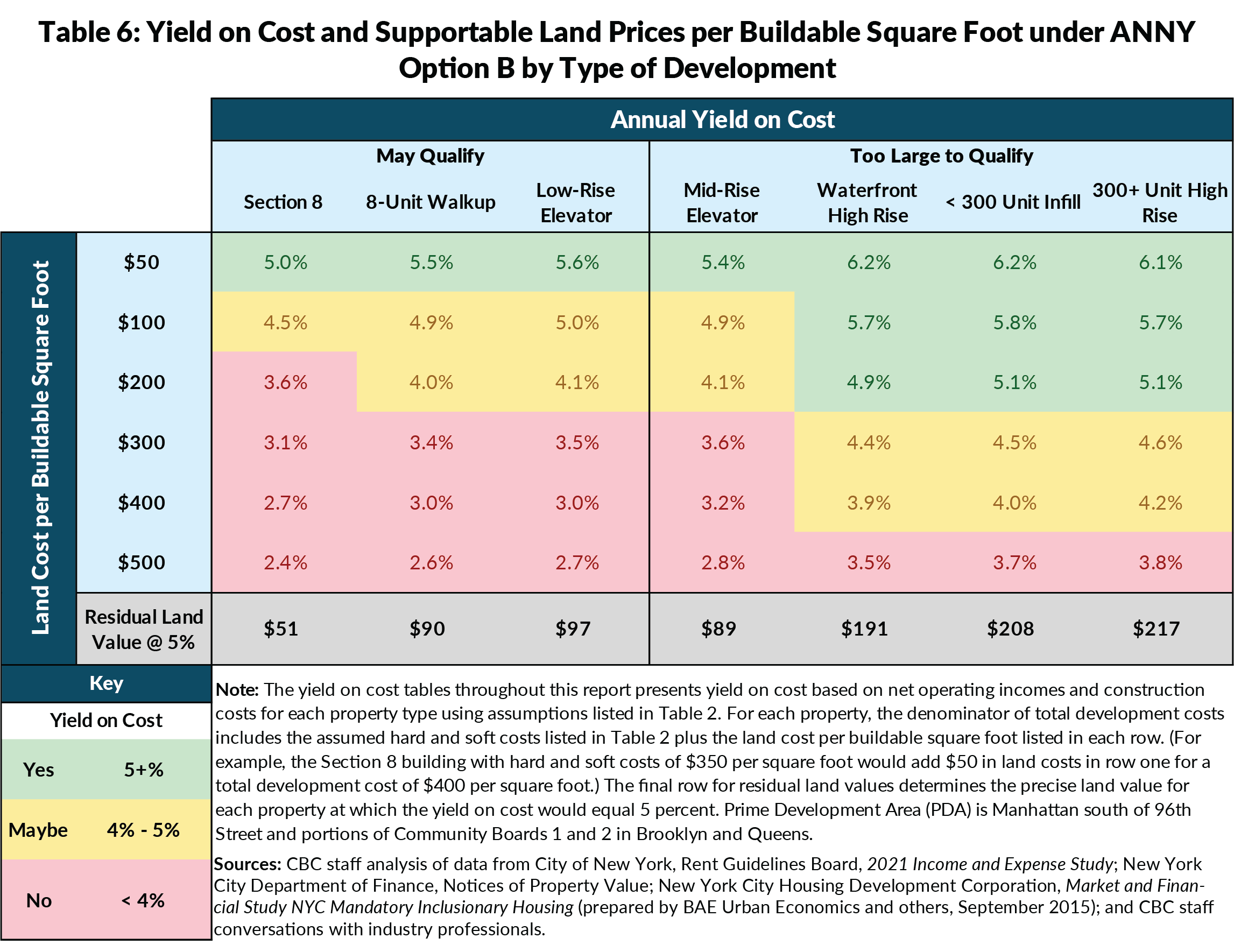

Option B Viable for Rental Development, but 29-Unit Cap Artificially Limits Development Potential

Table 6 illustrates the financial feasibility of the seven projects under ANNY’s Option B, which requires developers to set aside 20 percent of units at 90 percent of AMI. While this option is available only to projects with between 6 to 29 units, Table 6 applies those affordability restrictions to all projects, regardless of size. (Note that under the current 421-a program and market conditions, there is almost no development of rental housing with 29 or fewer units inside the PDA.14)

Under Option B, most projects in moderate- and middle-income neighborhoods would be feasible. Option B would generate a 5 percent YOC at land prices of approximately $90 to $100 per buildable square foot for most projects outside the PDA. In many neighborhoods, this would be sufficient to justify investment; in others, land prices under Option B may be less than prices under the current program, and development may slow down as land-owners and developers adjust their assumptions and return expectations to the new program.

However, with the exception of the 8-unit walkup, the other three typologies of outer-borough development would only be able to use Option B if they include 29 or fewer units. The Section 8 and Low-Rise Elevator buildings are already small enough that they could qualify for Option B if they reduced their unit counts to get under the 29-unit cap, but the Mid-Rise Elevator building would be too large to qualify.

Homeownership Option Unlikely to be Broadly Used but More Details Needed

Many questions remain about ANNY’s affordable homeownership option, including the conditions that would be placed on purchasers and developers. At a maximum of 130 percent of AMI, the program would likely support sales prices of no more than $750 per square foot, or approximately $650,000 for a two-bedroom apartment, which is well below median pricing in most areas of the city that can support condo development.15 Given the additional regulatory hurdles and time required to participate in the program, as well as the likelihood that asset tests placed on buyers would limit the potential pool of purchasers and potential resale options (neither of which is in the current legislation), the incentive likely would be used in conjunction with other subsidized homeownership programs, similar to the Mitchell-Lama cooperative or Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) programs. If developers could build condominium projects that were sufficiently profitable at those sales prices, they likely would prefer to sell them without the additional restrictions and approvals required to qualify for the ANNY homeownership option.

ANNY Would Produce Less Rental Housing Than the Current Program and Likely Constrain Future Rental Housing Production in New York City

Allowing 421-a to lapse would significantly reduce rental housing development, worsen the city’s existing housing supply shortage, and make New York City’s already scarce and costly rental housing scarcer and more expensive. New York City does not produce enough housing, even with the 421-a program in place.16 Without the 421-a program, some but not all of the rental housing pipeline would shift to condominiums, which do not have affordability set-asides. Other housing sites simply would not get built, and housing production rates would fall even further than their already low levels.

ANNY would produce more housing than if 421-a were to lapse, but likely would yield less housing development than under the current version of the program.

Of the typologies analyzed in this report, two types of rental projects would be feasible under ANNY:

- High-density rentals in areas that command very high rents, and

- Buildings outside the PDA with fewer than 30 units, small unit sizes, and low construction costs.

By contrast, most buildings with 30 or more units in moderate- and middle-income neighborhoods would not be viable under ANNY because market-rate rents in these areas are not high enough to cross subsidize the affordability levels required under Option A.

The diverging impacts of Option A by neighborhood aligns with the findings of the financial feasibility study commissioned by the City to support the development of the MIH program. The MIH feasibility study found that inclusionary housing requirements work best in neighborhoods where rents are very high and would not be financially feasible for developers in other areas of the city. Similarly, that study found that mid-rise projects in middle-income neighborhoods were most affected by inclusionary housing requirements—the exact type of development that may not be feasible under ANNY Option A.17

Also, ANNY would make it harder for the City to increase development capacity through upzonings, particularly outside the Manhattan core. The lack of zoning capacity in many neighborhoods is one factor that contributes to New York’s sluggish housing production rate.18 Upzonings can incentivize new development by allowing more residential density than currently allowed by zoning. In most areas of New York City, upzonings make it easier to build mid- or high-rise housing where zoning permits only low-density development or prohibits housing altogether. However, as shown, these buildings may not be feasible under ANNY in most moderate- and middle-income neighborhoods. Thus, while an upzoning might create the theoretical capacity for development, ANNY’s deep affordability requirements could undercut the financial viability of any potential projects.

Furthermore, in outer-borough neighborhoods where as-of-right development capacity already exists, limiting Option B to sub-30-unit buildings may effectively place an upper bound on size of rental developments, even on sites that have the zoning capacity to accommodate denser development.

In some Manhattan neighborhoods, rental projects may become less competitive in the market for development sites. The land prices supported by the current 421-a program already are below what some condominium and commercial developers are willing to pay for land. Combined with rising construction costs, some rental sites in the core areas are at risk of going undeveloped or being built as other uses.

Finally, while this analysis did not assess whether permanent affordability provisions might reduce the feasibility of rental development projects, this outcome may be a possibility. Offering hardship options to exit affordability requirements or to convert from affordable rentals to affordable condominiums may help mitigate against this risk but must be well-designed to prevent misuse. Some buildings with permanently affordable units may require additional subsidy upon expiration of ANNY benefits to ensure continued feasibility and habitability.

Recommendations to Improve the ANNY Proposal

State lawmakers should authorize an as-of-right tax exemption designed to foster rental housing development, minimize disruption of land and development markets, and help the City meet its affordable housing production goals. Until State lawmakers pass a broader plan that successfully reduces construction costs, reforms the property tax system, and modernizes laws and regulations that increase operating costs, the need for an incentive will remain.19

Ideally, any successor to the 421-a program should meet the following criteria:

- Available as-of-right;

- Maximizes production of both market-rate and affordable units;

- Creates affordable units in the most cost-efficient manner;

- Subsidizes market-rate units only to the extent that they would not get built without incentives;

- Minimizes distortions or disruptions of land prices;

- Aligns with requirements of other City housing programs;

- Accommodates different market conditions throughout the city; and

- Subjects the program to periodic evaluation for effectiveness and efficiency.

ANNY meets some, though not all, of these criteria. While it would retain an as-of-right incentive, three changes would increase the production of both market-rate and affordable rental units in a cost-effective manner.

1. Better tailor affordability options to reflect different market conditions.

Property tax exemptions are necessary to stimulate the development of rental housing in every area of New York City, but market conditions vary widely by neighborhood. Accordingly, ANNY’s affordability set-asides should vary by neighborhood to reflect different market conditions in different areas of the city.

- Option: Create a new option for mid-rise projects outside the PDA. Most mid-rise projects outside the PDA are not feasible under Option A but are too large to access Option B, which is available only to small rentals. A third option at a higher average income band or a lower share of units would help make more projects feasible.

- Option: Offer Option B to all projects outside the PDA. Allowing mid-rise projects outside the PDA to use the affordability levels and shares available to Option B (20 percent set aside at 90 percent of AMI) would improve the financial feasibility of these projects. Option B’s affordability requirements would still reduce profitability, and therefore land prices, compared to the current 421-a program, but the reduction would be much less drastic compared to Option A. Many projects that would not be feasible under Option A would be feasible if they could be built under Option B.

2. Track and evaluate program usage to inform successor programs

ANNY or any other 421-a replacement program should come with greater transparency and public reporting of data to support a robust assessment of the program’s impact and effectiveness. Specifically, the City should produce the following reports, which would combine data sources already compiled by HPD, City Planning, and the Department of Finance, and make them more accessible for the public20:

- A database of ANNY project recipients that includes projects’ location, number of units (both market-rate and affordable and by level of affordability), construction year, exemption start and end years, and relevant data from the most recent property tax assessment roll;

- Reports on overall residential development trends, ideally summarized at the community district level, with information on the number of completions, including alterations and new construction; the number of projects and units by ownership status and tax class (rental, condominium, 1-3 family, etc.); and which if any subsidy programs, exemptions, or abatement the projects used; and

- Data on the pipeline of projects that plan to use the program. Currently, 421-a recipients do not certify and start receiving 421-a benefits until after construction is complete and they have received a temporary certificate of occupancy. Given that most construction projects take years to complete, and that 421-a historically has been renewed in five-year cycles, the public has limited information about how developers are (or are not) using 421-a, which is critically important when it comes time to renew or redesign the program. Developers should submit a simple, non-binding declaration of intent to use 421-a earlier in the process, such as when they start the housing lottery process with HPD.

3. Work with the City to align the incentive with other housing programs

421-a is one of the City’s most powerful tools for generating affordable rental housing, but its design does not align with the terms or provisions of other City housing initiatives. Ideally, the 421-a successor should harmonize with other affordable housing programs and not be misaligned in ways that cause delays, increase complexity, create confusion, or make building housing riskier and more expensive.

- Option: Modify ANNY and MIH to be compatible: ANNY does not align with the City’s MIH program or the Voluntary Inclusionary Housing bonus programs that were negotiated in previously approved neighborhood rezonings. While ANNY Option A is close to MIH Option 1, it would be calculated based on a percentage of units instead of a percentage of floor area used by MIH. ANNY Options B and C have no MIH analogues. Amending MIH to align with income levels and shares in ANNY would require a new environmental review and ULURP approvals, adding uncertainty and years to the process. City officials should identify alternative approaches for aligning MIH with ANNY or other 421-a replacements.

- Option: Clarify rules for projects receiving bond financing and/or other subsidies: The draft ANNY legislation also does not specify if projects that receive tax-exempt bond financing or discretionary City capital subsidies could also receive tax exemptions, and if there would be any restrictions on either bond financing, City subsidies, or the tax exemption. This uncertainty should be clarified.

Conclusion

While 421-a is flawed, a well-crafted successor program is necessary to ensure the continued production of rental housing in New York City. As State lawmakers consider a potential 421-a successor, they should design a program that is available as-of-right and maximizes production of both market-rate and affordable units in the most cost-efficient manner. State and City officials also should continue to take actions to reduce construction and operating costs, increase zoning capacity, and reform the property tax; actions that help meet the housing needs of New Yorkers, however, should wait for these changes. New York City already does not produce enough housing, even with the 421-a incentive in place. Approving a successor to the 421-a program is critical to ensuring that the city’s already scarce and expensive rental housing does not grow even scarcer and more expensive.

Amend It, Don't End It: Improve 421-a to Spur Rental and Affordable Housing Development

Amend it, Don’t End It: Improve 421-a to Spur Rental and Affordable Housing DevelopmentFootnotes

- Turner & Townsend, “International Construction Market Survey 2019” (accessed February 25, 2022), https://www.turnerandtownsend.com/en/perspectives/international-construction-market-survey-2019/.

- Engineering News-Record, “Construction Cost Index 2022” (accessed February 25, 2022), https://www.enr.com/economics.

- CBC staff analysis of data from City of New York Rent Guidelines Board, 2021 Income and Expense Study (April 15, 2021), https://rentguidelinesboard.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2021-IE-1.pdf; Paula Munger and Leah Cuffy, “National Apartment Association 2021 Survey of Operating Income & Expenses in Rental Apartment Communities” National Apartment Association (October 20, 2021), https://www.naahq.org/news-publications/national-apartment-association-2021-survey-operating-income-expenses-rental; and New York City Department of Finance Notices of Property Values for selected properties receiving 421-a benefits, https://a836-pts-access.nyc.gov/care/forms/htmlframe.aspx?mode=content/home.htm.

- CBC staff analysis of data from City of New York Rent Guidelines Board, 2021 Income and Expense Study (April 15, 2021), https://rentguidelinesboard.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2021-IE-1.pdf; Paula Munger and Leah Cuffy, “National Apartment Association 2021 Survey of Operating Income & Expenses in Rental Apartment Communities” National Apartment Association (October 20, 2021), https://www.naahq.org/news-publications/national-apartment-association-2021-survey-operating-income-expenses-rental.

- CBC staff analysis of data from the City of New York Department of Finance Notices of Property Values for selected properties receiving 421-a benefits, https://a836-pts-access.nyc.gov/care/forms/htmlframe.aspx?mode=content/home.htm.

- New York City Housing Development Corporation, Market and Financial Study NYC Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (prepared by BAE Urban Economics and others, September 2015), http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/plansstudies/mih/bae_report_092015.pdf.

- The rents and income levels for both the current 421-a program and for ANNY are based on median incomes for the New York metropolitan region, scaled to household size, as determined annually by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Rents at each income level are assumed to be 30 percent of a household’s pre-tax income. The most recent income levels for New York City can be found at: New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, “2021 New York City Area Affordable Monthly Rents” (accessed February 15, 2022), https://www1.nyc.gov/site/hpd/services-and-information/area-median-income.page.

- New York City Housing Development Corporation, Market and Financial Study NYC Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (prepared by BAE Urban Economics and others, September 2015), http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/plansstudies/mih/bae_report_092015.pdf.

- The results of this analysis are sensitive to changes in the basic assumptions listed in Table 2. For example, reducing construction costs or unit sizes would make a project more profitable, holding other assumptions constant, while reducing rental income or increasing operating costs would reduce profitability. The analysis also does not capture every type of operating revenue or expense, which can vary greatly among rental projects. Some buildings generate additional income from retail, parking, or commercial spaces. Operating costs also vary by size of building and location. Larger buildings achieve some economies of scale in their operations, but also employ more building service workers and offer more amenities than smaller buildings. Finally, estimated gross square footage per unit includes a building’s built area, including common areas, stairs and elevator cores, ground floor space, and mechanical areas.

- New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, “2021 New York City Area Affordable Monthly Rents” (accessed February 15, 2022), https://www1.nyc.gov/site/hpd/services-and-information/area-median-income.page.

- The City’s 2015 MIH feasibility study assumed a minimum investment return of 6 percent at a time when interest rates and capitalization rates (another metric used to value income-producing real estate assets) were higher than today. A more recent survey of capitalization rates for multifamily rental buildings in New York City found that developers expect returns ranging from 4 to 6 percent depending on the project. See: CBRE, Cap Rate Survey First Half 2021, p. 21, http://cbre.vo.llnwd.net/grgservices/secure/united-states-cap-rate-survey-h1-2021.pdf.

- Absent a tax exemption, capital subsidies and other incentives could also make the development feasible, but they are limited, costly, and may be less cost effective. Most of the City’s other affordable housing programs also provide tax exemptions through the 420-c and Article XI programs.

- As of January 2022, according to Miller Samuel data, the new development median rental price was $5,634 in Manhattan, $3,426 in Brooklyn, and $3,610 in northwest Queens. See: Miller Samuel Inc., Elliman Report: Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens Rentals January 2022 (January 2022), https://www.millersamuel.com/files/2022/02/Rental-01_2022.pdf.

- CBC staff analysis of data from New York City Department of City Planning, Housing Database Release 20Q4 (accessed February 23, 2022), https://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/data-maps/open-data/dwn-housing-database.page.

- According to Miller Samuel data, the median sales price for condominiums, co-operatives, and 1- to 3-family homes in the fourth quarter of 2021 was $800,000, with prices ranging from $575,000 in the Bronx to $1.17 million in Manhattan. This figure includes the resale of existing units and new construction. See: Miller Samuel Inc., New York City Real Estate Market Residential Brief 4Q 2021 (February 2022), https://www.millersamuel.com/files/2022/02/NYC4Q21brief.pdf.

- Sean Campion, “Strategies to Boost Housing Production in the New York City Metropolitan Area” Citizens Budget Commission (August 26, 2020), https://cbcny.org/research/strategies-boost-housing-production-new-york-city-metropolitan-area.

- New York City Housing Development Corporation, Market and Financial Study NYC Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (prepared by BAE Urban Economics and others, September 2015), http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/plansstudies/mih/bae_report_092015.pdf.

- Sean Campion, “Strategies to Boost Housing Production in the New York City Metropolitan Area” Citizens Budget Commission (August 26, 2020), https://cbcny.org/research/strategies-boost-housing-production-new-york-city-metropolitan-area.

- CBC previously noted several factors that increase the cost of development and discourage housing production, including outdated building and construction codes that require more expensive building materials or construction methods compared to other cities, as well as regulations like the Scaffold Law that increase the cost of development. See: Sean Campion, “Strategies to Boost Housing Production in the New York City Metropolitan Area” Citizens Budget Commission (August 26, 2020), https://cbcny.org/research/strategies-boost-housing-production-new-york-city-metropolitan-area.

- Existing data on the 421-a program is spread across multiple reports including HPD’s Affordable New York project-level databases, DCP’s Housing New York permitting database, and the Department of Finance’s Real Property Assessment Data file and Property Exemption Detail reports. Building a complete database of 421-a projects (and comparable projects not receiving 421-a) requires joining these four datasets and substantial work to clean and validate data to ensure accuracy. The City already uses these data sources to compile other reports, such as DOF’s Tax Expenditure Report and HPD’s annual reporting on its affordable housing production totals, which provide partial though incomplete information on 421-a activity and development trends, more generally.