Improving the New York City Subway System

Submitted to the NYC Council Committee on Transportation

Thank you for the opportunity to speak today. The Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization devoted to influencing constructive change in the finances of New York City and New York State government, including state authorities like the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA).

In May, subway on-time performance fell below 62 percent, and the 12-month rolling average for subway car reliability has fallen to lows not seen since at least 2009. The forces that shaped the decline in subway reliability and high profile failures, such as the derailment of an A train in July, have been in operation for years. Unfortunately, the current debate on what is needed to stabilize the system and who should pay for it risks perpetuating these same forces.

My testimony today will highlight the ways the MTA has long underinvested in its infrastructure and prioritized system expansions and enhancements over capital improvements that would bring the subway system to a state of good repair. I will also discuss how the MTA should rethink its funding framework to raise necessary revenues from the three categories of beneficiaries of the region’s mass transit system: riders, taxpayers, and drivers. As part of this discussion, I will emphasize that the current public debate over whether the State or the City should provide more funding for the MTA overlooks the fact that taxpayer revenue will be used to foot the bill regardless of which level of government imposes the tax. And that the majority of the MTA’s funds are now provided by New York City residents and businesses.

Misplaced Priorities in the MTA’s 2015-2019 Capital Program

Although the MTA has been making substantial investments in the subway system for more than 30 years, parts of the system are not in a state of good repair. A long period of neglect prior to 1982 and constant wear and tear since then mean additional investments for repairs or replacement are needed.

In planning for the 2015-2019 capital program, the MTA staff released the latest 20-year needs assessment in October 2013. This document focuses on the capital investments needed to rebuild and replace the thousands of assets that comprise the MTA network’s vast infrastructure—including the New York City subway—and to ensure that the existing systems continue to deliver transportation services safely and reliably. The document guides the agency’s five-year capital plan by highlighting the continuing investments needed in subway cars, signals, track, stations, equipment, and other assets over the five-year period.

Though the 20-year needs assessment laid out the size of investments needed to bring the system to state of good repair, it did not anticipate funding or fulfilling all the needs. MTA staff developed the list of projects to be undertaken while keeping in mind the agency’s capacity to execute capital projects and the public’s willingness to endure service disruptions necessary to carry them out. Thus, the needs assessment likely understated MTA infrastructure needs, particularly in the subway system, which operates around the clock.

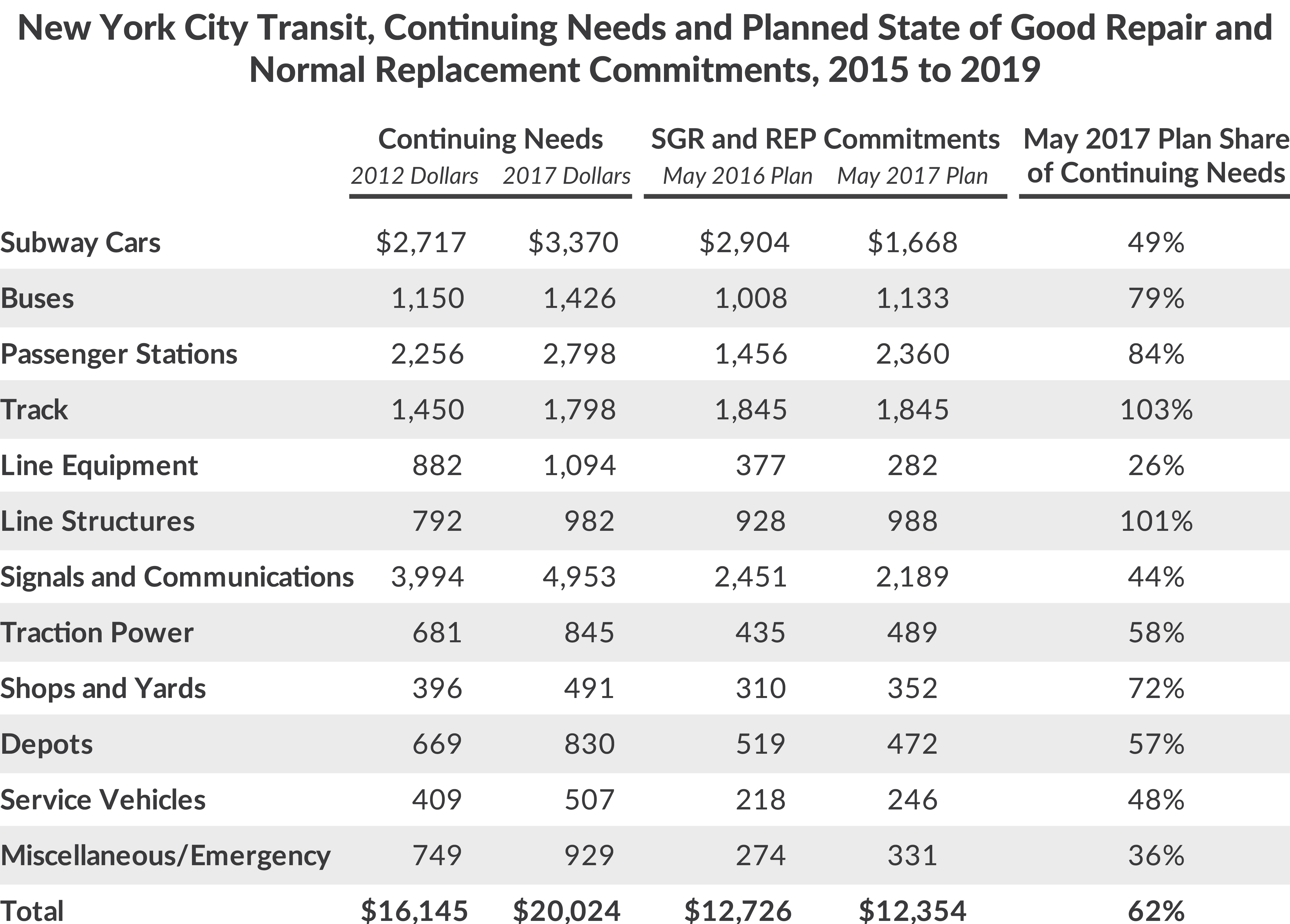

Despite the development of the needs assessment, the MTA’s originally approved 2015-2019 capital program did not invest enough in bringing the subway system to a state of good repair. (See Table.) The 20-year needs assessment listed $16.1 billion in continuing needs for the subway, but the originally approved plan included only $12.7 billion in state of good repair and normal replacement investments. The originally approved plan did not meet investment targets for 7 of 10 categories of subway system assets including shortfalls of 39 percent for the signals and communications systems, and 57 percent for line equipment such as ventilators, pumps, and tunnel lighting.

Despite these levels of underinvestment, the 2015-2019 capital plan included more than $4.8 billion in system expansions. Work on East Side Access, started as part of the 2005-2009 capital program, continues in the 2015-2019 program, and was joined by two new expansions: Phase Two of the Second Avenue Subway and Penn Station Access, a project to build new Metro-North Stations in the Bronx and bring the system into Penn Station. These expansions accounted for more than 16 percent of the originally approved plan.

If the 20-year needs assessment set a low bar for progress toward achieving a state of good repair in the subway system and the originally approved 2015-2019 capital program plan did not meet even that low bar, then the amended capital plan, passed by the MTA board in May, represents a move further in the wrong direction.

The comprehensive amendment to the 2015-2019 capital plan presented in May 2017 increased the size of the plan more than 10 percent; however, despite this increase, the agency still intends to invest less than is required to keep the system in state of good repair and to enable current capacity to be used effectively. The amendment decreases sums dedicated to subway signals and communications systems, subway cars, and subway equipment such as vents, pumps, and tunnel lighting. Most of the net increase came from increased commitments to network expansions, the addition of nearly $2 billion for the Long Island Rail Road Expansion Project and $700 million for Phase II of the Second Avenue Subway.

Pursuing these expansions and enhancements allocates substantial sums, and implicitly commits even larger sums in the future, to expanding the transit network, without adequately addressing the causes of service deterioration. Instead of an all-hands-on-deck effort to improve transit service and reliability, more than one-fifth of the current capital plan supports highly visible and popular expansions. Ideally the MTA could both bring its system to a state of good repair and expand the system. However, the system’s recent performance and constrained ability of the agency to execute the capital plan forces the MTA to make difficult choices about where to allocate funds.

Funding the System Over the Long Term

Remedying this short fall in investments in the subway system’s state of good repair in the short term does not require additional capital funding. As of March of this year, more than $80 billion has been authorized for capital plans spanning the 2000 to 2014 period. Of this sum, more than $18 billion remains unspent and $9.2 billion remains uncommitted to construction projects. These uncommitted funds, and funds in the current 2015-2019 capital program can and should be re-tasked to work that can accelerate the process of bringing the subway to a state of good repair.

Over the longer term, the MTA, and policymakers, should pursue a different funding framework for the transit agency, one that recognizes three types of revenue to support mass transit: fares, paid by riders; tax subsidies, paid by taxpayers in general; and motorist cross-subsidies, paid by drivers through bridge and tunnel tolls, fuel taxes, and license and registration fees.

CBC has advocated that between 45 and 50 percent of mass transit expenses should be funded by fares; linking fares to expenses maintains pressure on management and labor to keep expenses down, and it makes clear to riders the link between collective bargaining and fares. The remaining share of expenses should be paid with tax subsidies (25 to 30 percent) and a cross-subsidy from motor vehicle users (20 to 25 percent) via tolls, other user fees, or both. Though the current mix of revenues meets the guidelines for fares, it does not rely enough on cross-subsidies from motorists, who contribute only 12 percent of MTA’s mass transit funds.

The implication of this framework for the current situation means the MTA should seek additional motor vehicle use charges to cross-subsidize transit. This can be done by increasing current user charges such as tolls, motor fuel taxes, and license and registration fees. Other approaches would create new sources of funding, such as tolling the City’s East River Bridges or the adoption of a more-comprehensive congestion pricing system. Altering the tax and fee structure for taxicabs and for-hire vehicles in the MTA region could generate revenue through a new tax or fee or by earmarking the revenues from existing taxes or fees for the MTA.

CBC has urged adoption of a mileage-based user fee, also known as a vehicle-miles traveled (VMT) tax, which would better reflect the actual use of roads and bridges than motor fuel taxes, particularly as vehicles become more fuel efficient. With the use of GPS technology, a VMT fee can be used to more accurately price a road’s use according to its congestion.

Funding Stabilization and Ongoing Operations

The stabilization plan presented by the MTA Chairman last month is sensible and ambitious. The plan includes $380 million in new capital investments, a one-time cost that can be funded from the current capital plan, and $456 million in recurring operating costs, the bulk of which will support the hiring of 2,700 permanent new workers.

The Chairman suggested these costs be split evenly between two entities: the State and the City. This is a false choice. Neither the City nor the State is a person with a checking account. The MTA is asking taxpayers—most of them New York City residents—to foot the bill.

In 2016 the City contributed approximately $835 million in operating subsidies for the MTA, $229 million in capital contributions, and $142 million in debt service on bonds issued by a City-sponsored authority to pay for the extension of the 7 train to Hudson Yards. Residents and businesses that pay local taxes to support this direct contribution also pay a large share of the regional and statewide taxes the State allocates to the MTA. A conservative estimate is that New York City residents and firms pay approximately three-fourths of regional taxes—$3.4 billion of $4.6 billion in 2016—and approximately 45 percent of statewide taxes—$538 million of $1.1 billion in 2016. These “City” contributions total $4.7 billion, in contrast to the $2.1 billion paid by taxpayers outside the city.

Instead, fair division of the responsibility for these additional, ongoing operating expenses should rest on the region’s motor vehicle users and the MTA and its workforce.

I have already explained CBC’s argument for an increase in motor vehicle cross-subsidies so I will forgo additional discussion at this time. In addition, the MTA and its workforce should more aggressively pursue efficiencies at the agency to make the stabilization plan self-sustaining. A cooperative arrangement between MTA management and the Transport Workers Union, the representative for most of New York City Transit’s workforce, could provide significant productivity savings to help cover the cost of the added workers. Examples of potential savings include altering night shift differentials, which would reduce the cost of maintenance in the expanded Fasttrack program, and use of “split shifts” for operators and conductors to reduce subway operating costs.

The Mayor’s recent proposal is not consistent with CBC’s funding framework for mass transit services. Taxpayers, particularly New York City taxpayers, already subsidize the MTA more than they should. Approximately 40 percent of the mass transit budget is funded by taxpayer subsidies; of this, nearly three-fourths comes from individuals and firms in New York City.

The discussion around this proposal is constructive in that it invites serious consideration of the MTA’s long-term needs. However, the funding stream or streams to support these long-term needs ought to come from motorists, either from congestion pricing or other charges for motor vehicle use.

To the extent that the Mayor is now endorsing half-price MetroCards for low income individuals—a policy that CBC has previously endorsed—such a program does not require a new tax, and should be funded with existing City resources.

Thank you. I welcome the opportunity to answer any questions.