Improving the Way New York Pays for Medicaid

Governor Andrew Cuomo’s budget proposals for fiscal year 2012-13 include an important first step towards fixing a longstanding flaw in the way New York pays for its Medicaid program. Under current policy New York’s counties are required to pay more than $7.1 billion for Medicaid in the current state fiscal year 2011-12, or 13 percent of the $54 billion in projected total expenditures. This large local government share is unusual, inequitable, and inconsistent with the new local property tax cap; it ought to be revamped, and the Governor’s proposal makes progress toward that goal.

The proposal would require the State to assume over a three-year period full responsibility for the growth in Medicaid costs. The growth in localities’ Medicaid expenses has been capped by statute at 3 percent annually since 2005. The cap has helped mitigate the financial burden on local governments of the much greater growth in total Medicaid costs, which has averaged 5 percent since 2005. But the capped growth rate still leaves a substantial budgetary challenge given the adoption in June 2011 of a 2 percent property tax growth cap.

A full state takeover of Medicaid cost growth would eliminate the budget squeeze caused by the inconsistent caps. The Governor’s proposal accomplishes this through a three-year phase in. The State would assume 1 percent of the growth rate starting January 1, 2013. This would result in relief for counties and put the local Medicaid growth rate in line with the property tax cap growth rate of 2 percent when counties adopt their next budget in December 2012. (County budgets follow the calendar year, except in New York City where the fiscal year begins July 1). Over the next two years, the State would assume responsibility for the remaining 2 percent growth rate by picking up an additional 1 percent effective January 1, 2014 and January 1, 2015. Beginning in 2015, local Medicaid costs would be fixed, allowing counties to live more easily within the property tax cap in the future. In state fiscal year 2015-16 this proposal will save local governments $370 million. Roughly 70 percent of those savings will accrue to New York City.

In addition to providing localities with some relief, this proposal is an important first step towards bringing New York’s Medicaid financing policy in line with the norm in other states and ending an inequitable distribution of substantial Medicaid costs among local taxpayers.

No other state requires localities to contribute so much to pay for Medicaid. Fully 22 states do not require local governments to contribute anything towards Medicaid. Of the 27 other states that have a local share, most require that it cover only a small portion. The local funding in California, the state with the next largest local share totaling $1 billion, represents just 2.5 percent of total Medicaid expenditures, far below New York’s 13 percent.

New York’s current local share policy is inequitable because low-income areas tend to have higher Medicaid enrollment and utilization than more affluent areas. Each county’s local share reflects the level of spending within its borders, meaning that low-income counties – and the residents who pay taxes there – pay more towards Medicaid relative to income and property value than those living in more affluent counties.

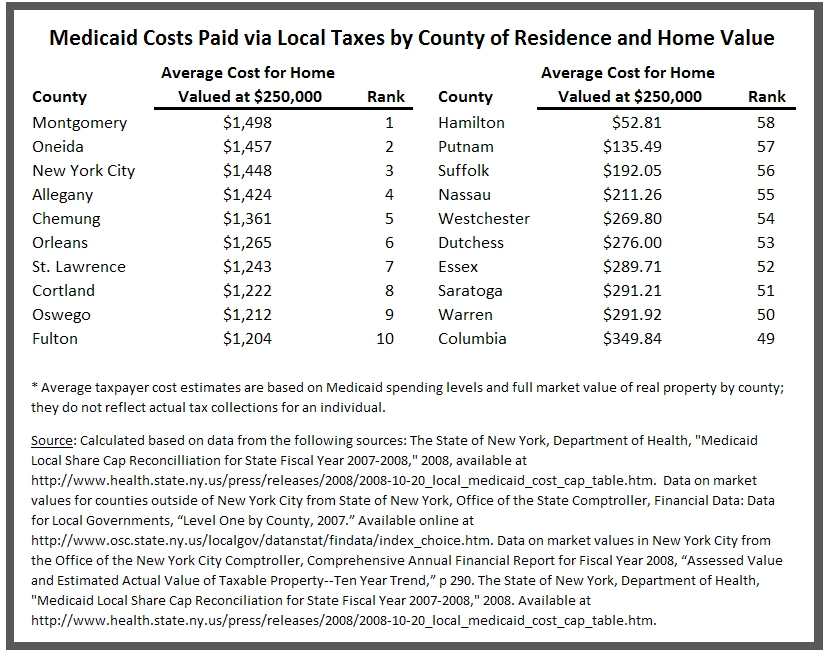

To illustrate the point we have calculated, based on Medicaid spending in 2008, the amount paid by taxpayers towards Medicaid with equivalent home values in different counties through their county property taxes. The chart below shows localities with the highest and lowest Medicaid tax burdens based on property values of $250,000.

The plan to cap the cost to counties in 2015 is a significant step that will help counties live within the statutory property tax. However, the counties and New York City will still be paying for nearly $8 billion of Medicaid costs. This inequitable and unusual burden will still need to be addressed. As they appropriately take credit for making progress in righting a longstanding wrong, the Governor and legislative leaders should at the same time begin planning for more far reaching, longer term initiatives that will fully solve the problem.