Medicaid Redesign – Significant Progress On A Tough Task

The Medicaid Redesign Team appointed by Governor Andrew Cuomo was given a difficult job – reduce Medicaid spending significantly while improving the quality of care provided to the indigent. The Team has made significant progress in at least two ways. First, the package approved by the Team late last month, which the Governor added to his budget proposal last week, would result in a rare year-over-year reduction in Medicaid spending. State spending for the program would fall more than 4 percent.[1] This is a significant departure from past practices. Medicaid spending increased an average of more than 6 percent annually between 1995 and 2010; year-to-year declines occurred only three times in that period.[2]

Second, and perhaps most importantly, the Team changed the dynamic of Medicaid budgeting by focusing many of the stakeholders on the same goal: controlling spending while improving quality of care. The collaborative process has been far less divisive than previous efforts to trim Medicaid spending, and it promises to be a useful model as reform efforts continue.

While the Team’s efforts are commendable, the gains are not a long-term solution to the challenge of Medicaid cost containment. The praiseworthy steps included in the package are accompanied by more conventional and less well targeted cuts to provider payment rates, as well as actions to raise revenue to support spending and a controversial approach to dealing with malpractice costs.

Overview of the Package

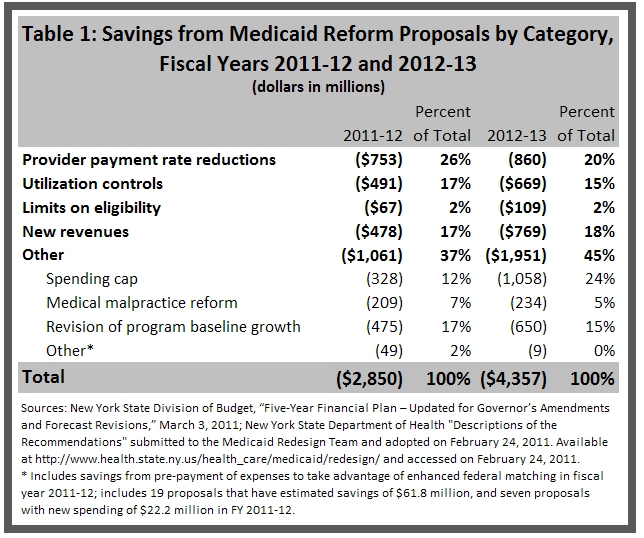

The proposals included in the Governor’s budget can be placed into five categories. The first three - reductions in provider payment rates, controls on excessive utilization, and eligibility limits – address the basic forces that drive expenditure increases. A fourth category includes measures to raise new revenue to support spending; this helps close budget gaps, but does not cut costs. The last group is “other” actions that fit none of the other four categories.

Table 1 summarizes the two-year impact of the Governor’s proposals using these categories. In the coming fiscal year about 45 percent of the savings are due to measures taken to control the three driving forces, with rate reductions being the largest single component (26 percent). Revenue enhancements comprise 17 percent and the other measures 31 percent.

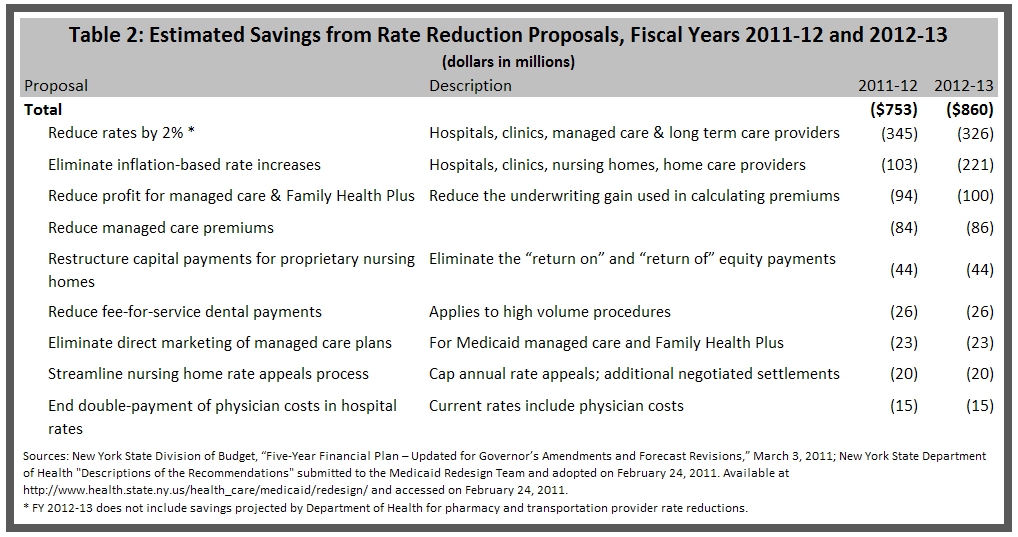

Reductions in Provider Payment Rates

The rate reductions that account for one-quarter of total savings are accomplished primarily by across-the-board actions affecting all institutional providers including hospitals, nursing homes and clinics. (See Table 2.) The inflation-based increases usually budgeted are eliminated, and base rates are cut 2 percent for combined savings in the next fiscal year of more than $440 million. Two proposals that reduce premium rates for managed care organizations would result in $178 million in combined savings.

The package includes few targeted rate reductions, and no broader reforms of provider payment methods. A pair of proposals relating to nursing homes would save a combined $64 million per year. New York’s nursing home rates are among the highest in the country and were 30 percent above the national norm in 2007.[3] The first proposal would eliminate certain payments for capital investments made by proprietary nursing homes ($44 million in annual savings); the second would continue a cap on payments stemming from nursing home rate appeals and seek to streamline that process by negotiating settlements ($20 million in annual savings). A broader proposal to overhaul the method by which nursing home payments are set in order to provide greater incentives for efficiency was not included in the package, although previously enacted payment reforms that take effect on July 1 have been retained. Also dropped were proposals to change hospital payment practices to limit subsides for graduate medical education.

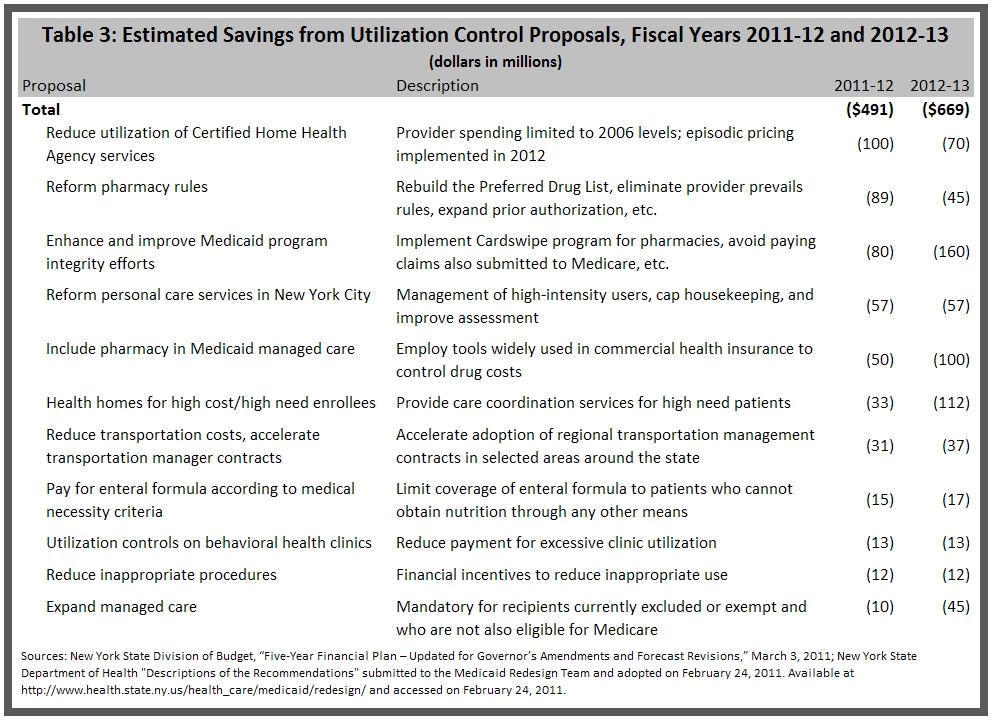

Controls on Excessive Utilization

Measures to control excessive utilization of Medicaid services account for 17 percent of the estimated savings in the next fiscal year. Controls on long-term care services are a much needed component of the package.

Long-term care costs topped $12 billion in 2008, or roughly a quarter of all Medicaid spending in the state, and they have experienced alarming growth.[4] Two proposals focus on reducing that utilization. (See Table 3.) The first would save $100 million in fiscal year 2011-12 by limiting payments to Certified Home Health Agencies (CHHA), which provide short- and long-term nursing and personal care. Per recipient costs in the CHHA program increased 76 percent from 2003 to 2008, reflecting a 56 percent increase in unit costs and an 11 percent decline in the number of recipients.[5] The proposal would cap payments to CHHAs based on 2006 costs and eventually reform the payment model for those agencies. Also, over the next two years the state would move many recipients from those agencies into the Managed Long Term Care program.[6]

The second proposal would limit spending on personal care, a service where spending increased nearly 40 percent from 2003 to 2008. Use of personal care, which includes housekeeping, meal preparation, bathing and toileting, would be restricted in New York City where much of the growth in the program has occurred. High intensity users of the service would be more closely managed, housekeeping would be capped at eight hours a week and assessments of recipients would be improved. Those restrictions would save an estimated $57 million annually.[7]

The package also includes proposals to control utilization by expanding managed care enrollment and by providing better care coordination for high needs individuals. Specific initiatives to control prescription drug use and to limit transportation costs also represent significant savings that still protect patients’ quality of care.

Eligibility Limits

Three proposals in the package affect eligibility. Complicated income and asset restrictions in New York allow individuals to become “medically-needy” and eligible for Medicaid. Though these provisions apply to anyone seeking Medicaid benefits, they commonly affect applicants seeking long-term care services because those costs are so high.

Under one proposal, the Medicaid Inspector General would assume responsibility for all estate recovery actions, saving an estimated $39 million in fiscal year 2011-12 and $52 million each year thereafter.[8] Responsibility for asset recovery currently lies with the counties. Since money recovered is given to the state, the counties have little incentive to use their limited resources on recovering those funds. In a survey of national Medicaid recovery efforts, New York ranked 32nd in recovery of nursing home spending; New York recovered only $30 million or 0.5 percent of the total spent on nursing home care.[9] An improved recovery process would save money and discourage those with significant assets from relying on Medicaid to pay for their care.

A second proposal would apply a 60-month “look back” period when determining eligibility for home-based long term care benefits. Currently, a “look back” period to identify asset transfers that may affect financial eligibility applies only when enrollees apply for home-based care after leaving a nursing home. This change would apply the look-back to all home-based entry points and likely increase recoveries for home care services, though the Department of Health has not yet provided a savings score for this proposal.[10]

The third eligibility proposal is to eliminate “spousal refusal.” New York now allows Medicaid coverage for an individual whose legally responsible adult (a spouse or guardian) simply refuses to support them. Although available data is limited, the Department of Health indicates spousal refusal is a common practice in obtaining home care. The Department estimates the proposal will save $28 million in the first year and $56 million annually thereafter; the savings estimate assumes that 45 percent of home care recipients are married and that 75 percent of those spouses refuse to make assets and income available for care.[11]

New Revenues

About 16 percent of the “savings” in the package comes in the form of new revenues to support the Medicaid program. This includes $370 million in unspecified actions in the Health Care Reform Act account. This is a special purpose account with dedicated revenues of various sorts that supports health care programs. Presumably funds in these dedicated accounts will be transferred to offset what otherwise might have been charged to the General Fund for Medicaid. Two other revenue measures are a surcharge imposed on office-based surgery and radiology to yield $58 million and $99 million in the next two fiscal years,[12] and an initiative to increase federal funding for certain school based health care programs by $50 million and $100 million in the next two fiscal years.[13]

Other Actions

More than $1 billion of the $2.85 billion in savings in the package, or 39 percent, come from actions that do not fit within one of the categories above. In some cases, there are serious questions about how these initiatives will be implemented.

One key element of this group is the innovative proposal to implement a program-wide spending cap that would limit annual program expenditures to the 10-year growth rate of the medical segment of the Consumer Price Index (roughly 4 percent). The legislation would require the State Health Commissioner to monitor program spending through monthly and quarterly reports. If the health care industry cannot achieve savings to meet the cap requirements, the Commissioner would be empowered to limit rate increases, impose utilization controls and take other actions to do so.[14]

This initiative promises to transform the way the Medicaid budget is developed. Limiting growth in a program known for frequent double-digit increases could be a meaningful starting point for bringing stakeholders together to close the budget gaps projected for the next few years. The cap promises to force providers to participate in finding spending reductions, rather than oppose them.

However, significant questions remain about how this new budget process would be implemented. The legislation indicates that expenditures would be monitored through monthly and quarterly reports, but how would the state ensure that the limits are enforced in a timely manner?

The spending cap appears to apply only to Medicaid spending administered by the Department of Health, and not to the nearly $6 billion in spending administered by the Office of Mental Health, the Office for Persons with Developmental Disabilities, the Office for Alcohol and Substance Abuse Services, and the Office of Children and Family Services. Exempting these programs can limit the cap’s effectiveness. These offices manage programs with costs rising nearly on pace with long term care. For example, costs for individualized programs providing community rehabilitation services run by the Office for Persons with Developmental Disabilities increased 34 percent from 2003 to 2008, while enrollment in those programs grew 29 percent.[15]

A proposed reform to medical malpractice rules also falls into this category. This reform is the single largest savings item for the first year of the package at $209 million.[16] The initiative would cap non-economic damages available in medical malpractice suits at $250,000. The legislation would also establish an indemnity fund to pay for future medical costs for neurologically impaired infants. The proposal would also require hospitals to participate in initiatives to increase the quality of obstetrical care. While reforming medical malpractice makes good sense, it is unclear whether this specific cap on non-economic damages is appropriate or whether the indemnity fund is the correct mechanism to reduce costs related to obstetrical care. For the short-term these malpractice reforms may be a justifiable way to achieve savings, but a longer term look at options for malpractice reform may ultimately be more beneficial.

Finally, the Medicaid Redesign Team was able to meet the $2.85 billion savings target thanks to a reduction in the baseline estimate of enrollment and service use by the Division of Budget. The $475 million in savings derived from the re-estimate is nearly 17 percent of the total savings.

Conclusion

Both in the collaborative process that was followed and in the quality of many reforms adopted, the Medicaid Redesign Team and Governor Cuomo’s administration have taken substantial steps toward reforming the State’s Medicaid program. The package developed includes targeted actions that promise to improve the efficiency and quality of care supported by Medicaid. In addition, the innovative approach of a cap on overall spending growth has potential to improve dramatically the dynamic of budgeting for Medicaid. The effective savings measures should be implemented speedily, and the new cap should be tested carefully in the coming year. But some cautionary notes also should be sounded. The added revenues will push up the cost of care, and future efforts should be pursued to reverse the new assessments. The malpractice proposal may prove acceptable and viable in the near term, but other reforms may be needed in the long-term. Finally, future savings in line with the goal of the innovative cap strategy will require broad changes in the way providers are paid and even greater efforts to limit excessive utilization through managed care and other new controls. Medicaid redesign is a story that will be continued.

Footnotes

- New York State Division of Budget, “Five-Year Financial Plan – Updated for Governor’s Amendments and Forecast Revisions,” March 3, 2011. State spending is adjusted to include federal funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

- New York State Office of the Comptroller, “Summary of Annual State Spending and Receipts.” Available at http://www.osc.state.ny.us/finance/index.htm and accessed on March 1, 2011. Year-to-year reductions occurred in 1996, 1997 and 2008.

- Rates from report prepared for the American Health Care Association. Eljay, LLC. “A Report on Shortfalls in Medicaid Funding for Nursing Home Care,” November, 2009. The study does not include rate information for 11 states: Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Delaware, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Mexico, West Virginia.

- The Lewin Group, “Analysis of the New York State Medicaid Program and Identification of Potential Cost-Containment Opportunities,”p. 9, prepared for The Citizens Budget Commission, October 22, 2010.

- Ibid. 9.

- Medicaid Redesign Team, “Proposals Approved by the NYC Medicaid Redesign Team,” Feb. 24, 2011, Proposal #5, http://www.health.state.ny.us/health_care/medicaid/redesign/.

- Medicaid Redesign Team, “Proposals Approved by the NYC Medicaid Redesign Team,” Feb. 24, 2011, Proposal #4652, http://www.health.state.ny.us/health_care/medicaid/redesign/.

- Medicaid Redesign Team, “Proposals Approved by the NYC Medicaid Redesign Team,” Feb. 24, 2011, Proposal #102, http://www.health.state.ny.us/health_care/medicaid/redesign/.

- Congressional Research Service, “Medicaid Coverage for LTC: Eligibility, Asset Transfers, and Estate Recovery,” 2008. Analysis of CMS, Form 64 data published by B. Burwell. Estate Recovery Amounts: state-reported data from CMS Third Party Liability data, Probate amounts, 2004TPLCollections.xls http://www.cms.hhs.gov/ThirdPartyLiability/.

- Medicaid Redesign Team, “Proposals Approved by the NYC Medicaid Redesign Team,” Feb. 24, 2011, Proposal #1,116, http://www.health.state.ny.us/health_care/medicaid/redesign/.

- Medicaid Redesign Team, “Proposals Approved by the NYC Medicaid Redesign Team,” Feb. 24, 2011, Proposal #18, http://www.health.state.ny.us/health_care/medicaid/redesign/.

- Medicaid Redesign Team, “Proposals Approved by the NYC Medicaid Redesign Team,” Feb. 24, 2011, Proposal #264, http://www.health.state.ny.us/health_care/medicaid/redesign/.

- Medicaid Redesign Team, “Proposals Approved by the NYC Medicaid Redesign Team,” Feb. 24, 2011, Proposal #13, http://www.health.state.ny.us/health_care/medicaid/redesign/.

- New York State Division of Budget, 2011-12 Article VII Bills Amendments, HMH New Part H, March 3, 2011. Available at http://publications.budget.state.ny.us/eBudget1112/1112_30DayAmendments.html.

- CBC analysis of data provided by The Lewin Group, “Analysis of the New York State Medicaid Program and Identification of Potential Cost-Containment Opportunities,” prepared for The Citizens Budget Commission, October 22, 2010.

- Medicaid Redesign Team, “Proposals Approved by the NYC Medicaid Redesign Team,” Feb. 24, 2011, Proposal #131, http://www.health.state.ny.us/health_care/medicaid/redesign.