NYS Budget Outlook

Brighter Economy Has Not Closed Gaps; Focus Should Be Spending Restraint, with More Sunshine on Basic Breakouts

Executive Summary

The New York State Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Budget came amid an improving economic outlook. However, the resulting rising tax receipts are not enough to eliminate the New York State’s annual or structural budget gaps.

The Citizens Budget Commission’s (CBC’s) analysis of the Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Budget proposed by Governor Kathy Hochul finds that:

- Higher projected State tax receipts due to improved economic conditions help reduce budget gaps;

- Underspending, cash management/pre-payments, and proposed savings reduce near-term budget gaps more than improved receipts;

- Fiscal year 2025 is balanced, but the out-year gaps of $5.0 billion to $9.9 billion are significant and unlikely to disappear by virtue of greater than projected economic growth;

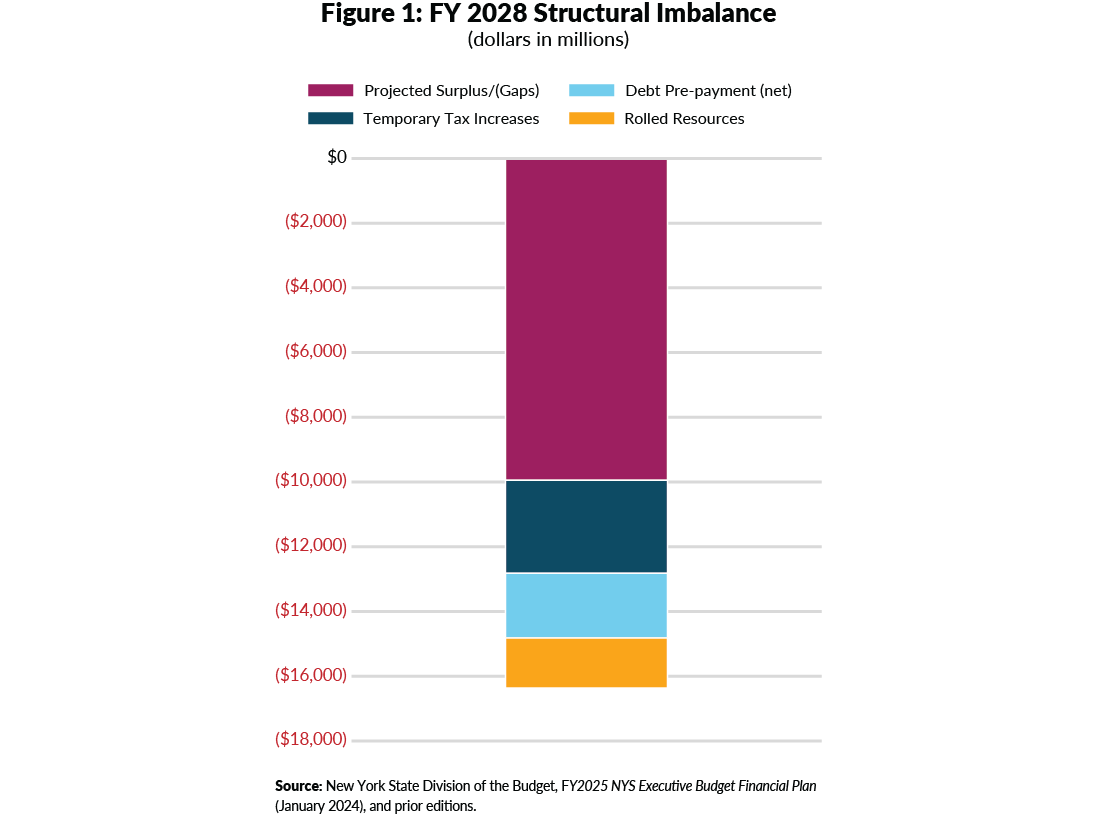

- The State’s structural budget imbalance exceeds $16.4 billion in fiscal year 2028, once the use of nonrecurring resources is taken into account;

- Even after savings proposed in the Executive Budget, Medicaid and school aid spending would continue to grow at rates that are not sustainable;

- State spending may well exceed the Executive Budget proposal, if Medicaid and school aid grow faster than the projected, due either to policy or health care cost and Medicaid enrollment trends;

- Further spending restraint remains necessary to close out-year budget gaps and achieve structural balance in the State’s financial plan; and

- The State has done little recently to meaningfully improve its budget and financial management processes, despite persistent shortcomings.

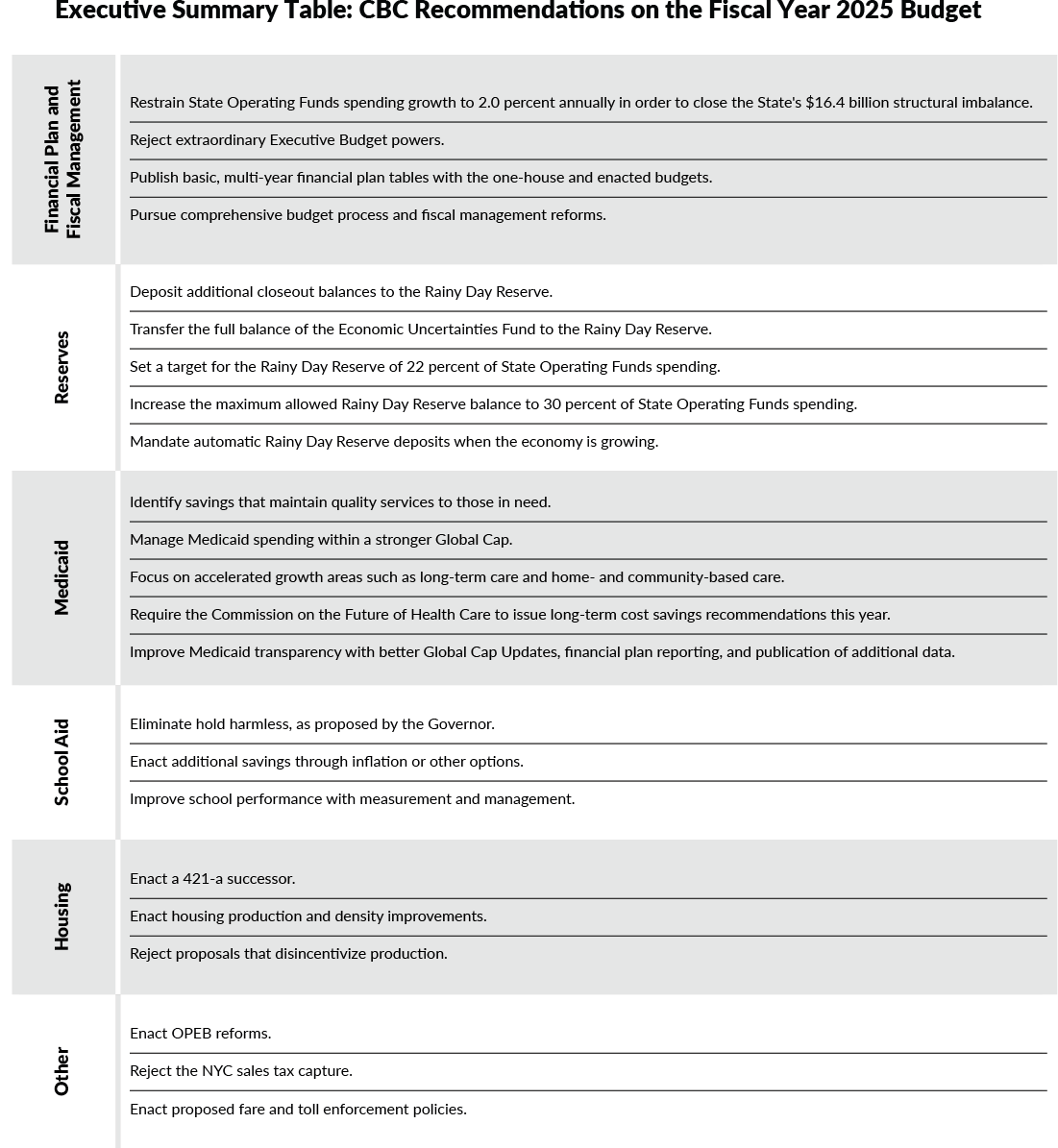

CBC recommends the State:

- Restrain spending growth, ideally to 2.0 percent annually, which would close projected gaps, stave off a fiscal reckoning, and achieve structural balance by fiscal year 2028;

- Does not increase taxes, since our nation-leading taxes and spending should be sufficient, and higher taxes risk competitiveness for residents and businesses;

- Deposit the additional fiscal year 2024 closeout surplus to the Rainy Day Reserve and make further structural improvements to reserves;

- Publish basic financial plan tables with one-house and enacted budgets;

- Rein in Medicaid spending growth by targeting savings in high-growth areas such as home- and community-based care, and by prioritizing enrollees with high needs and services with high impact benefits;

- Limit school aid spending growth by adopting the Governor’s proposal to eliminate hold harmless provisions, and target resources to districts and students with rising needs; and

- Enact policies that boost housing production and reject those that disincentivize new housing.

As both houses finalize one-house budget proposals and the Legislature and Executive negotiate the enacted budget, New York State leaders should prioritize long-term fiscal stability. Eliminating the structural imbalance will stabilize the State’s fiscal house and ability to consistently serve New Yorkers’ needs, maximize the benefit of public resources, and increase the State’s economic competitiveness.

Introduction

Governor Kathy Hochul’s Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Budget came as the economy continued to exceed expectations. A forecasted 2023 recession did not happen, improving the State’s tax receipts outlook and helping narrow budget gaps.

While the State’s outlook is improving, significant challenges remain: Projected budget gaps of up to $9.9 billion, a structural gap of $16.4 billion, and unsustainable spending growth in key programs require a significant, immediate response.

The Executive Budget took initial steps to re-align spending and revenues by proposing significant new savings, especially in the largest and fastest growing areas of the State budget: Medicaid and school aid. Unsustainable spending growth in those programs widens out-year budget gaps and crowds out other areas of spending.

Financial Plan Analysis and Findings

Tax Receipts

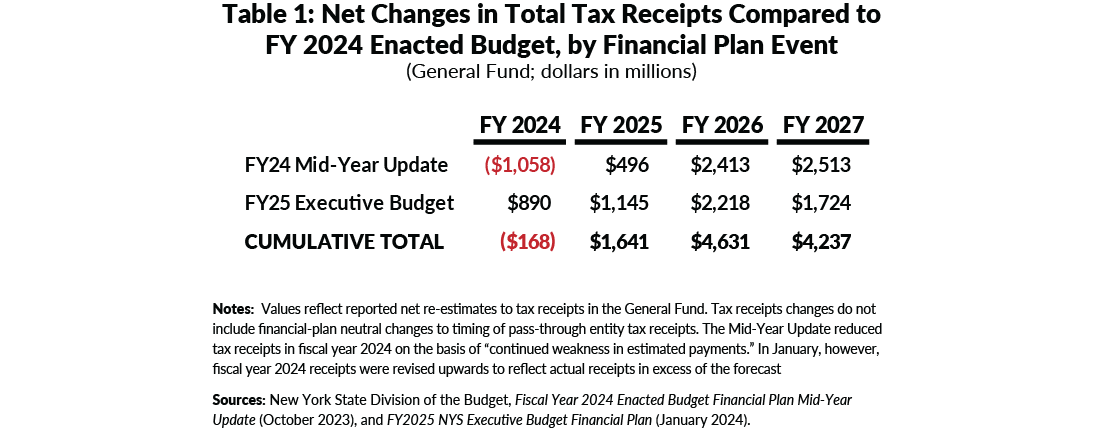

The State’s fiscal picture has changed significantly over the past two years, much of it due to shifting projections of tax receipts. Whereas in May of 2022 the financial plan included an unprecedented level of budget balance—showing no gaps in the budget year and all out-years—tax receipts were then repeatedly revised downward and budget gaps resurfaced, reaching nearly $14 billion annually by fiscal year 2026.1

However, the expected recession did not materialize in 2023. State economic indicators for total personal income, wage income, and employment growth all exceeded expectations, and inflation moderated as expected. The improving economic landscape strengthened the tax receipts forecast. In October 2023 and in January 2024, the State Division of the Budget (DOB) began to increase the tax receipts forecast in the out-years, including cumulative increases of $1.6 billion in fiscal year 2025, which helped close that year’s General Fund budget gap. (See Table 1.)

Fiscal Year 2024 Closeout

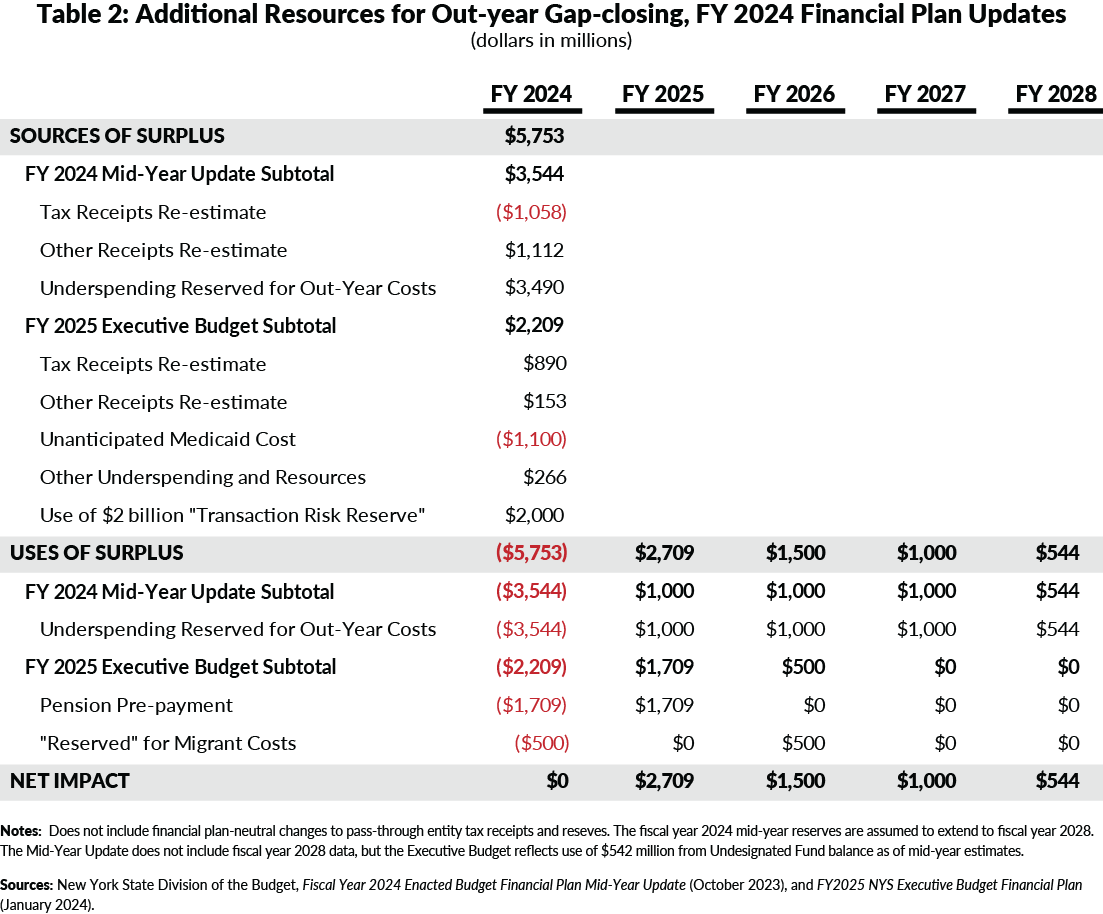

Despite the improved economic outlook and out-year tax receipts forecast, fiscal year 2024 tax receipts are still slightly lower, by $168 million, than the enacted forecast.2 Still, the State will close the year with additional funds—a surplus — available due to underspending and use of its Transaction Risk Reserve, which the Executive proposes to use to close gaps in the coming year and out-years.

As of the Executive Budget, $5.8 billion of current year resources are used to reduce out-year gaps. These resources are available primarily from underspending throughout the year and use of the Transaction Risk Reserve, an informal reserve to accommodate unexpected costs during the year. The Mid-Year Update in October 2023 reduced projected spending by $3.5 billion in fiscal year 2024, which was used to reduce out-year budget gaps.3 The fiscal year 2024 surplus of $2.2 billion, identified in the Executive Budget in January 2024, is proposed to be used to pre-pay pension costs and fund costs for migrant services in future years. (See Table 2.)

The State’s Revenue Consensus Report, wherein lawmakers agree on whether additional tax receipts are likely for closeout and the coming fiscal year, suggests that $1.4 billion in additional receipts are likely by year-end and through the coming fiscal year, raising the closeout surplus further.4 If additional receipts or lower spending is identified during the remaining closeout of fiscal year 2024, more resources may be available to reduce out-year gaps or deposit to the Rainy Day Reserve.

Fiscal Year 2025 and Out-Year Impacts

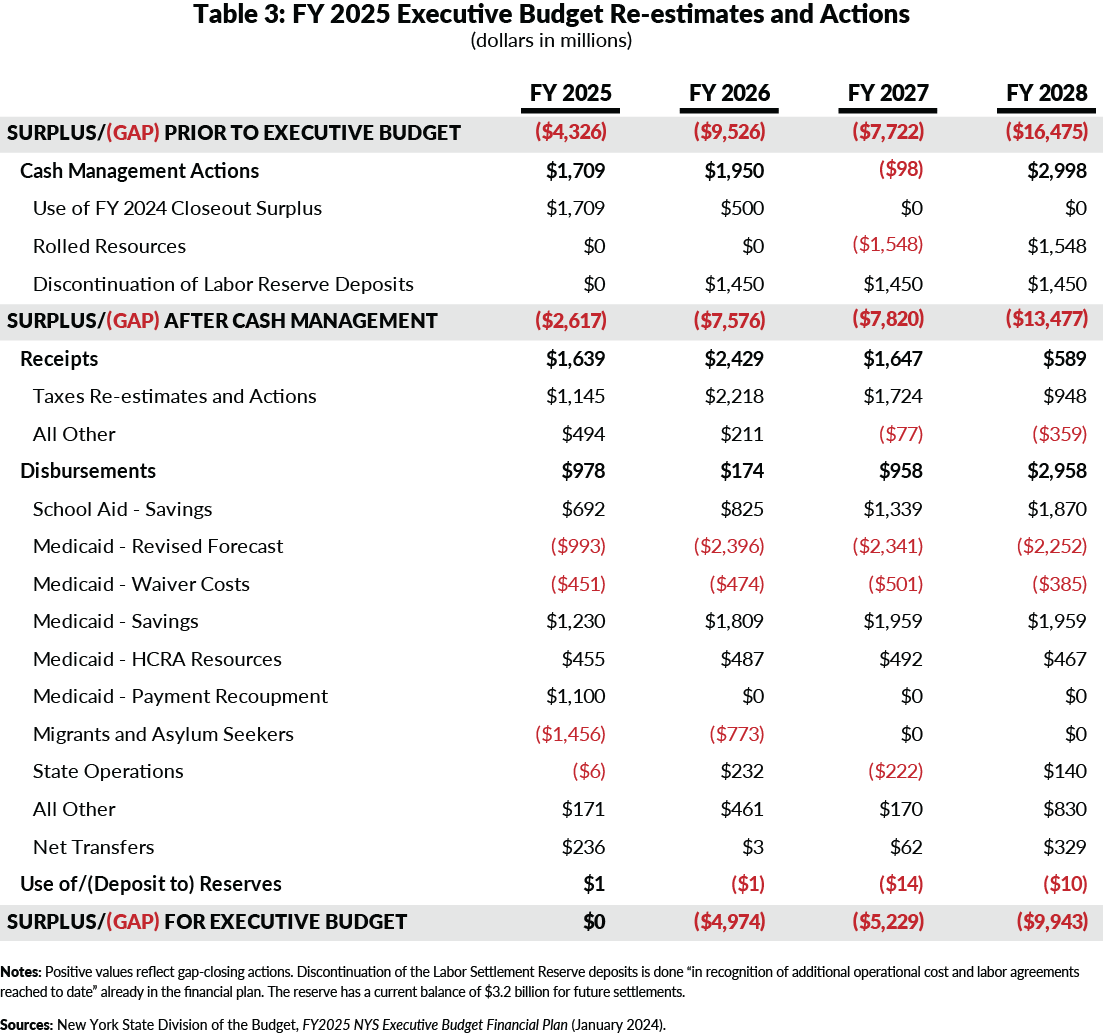

Prior to the Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Budget, the fiscal year 2025 gap was projected at $4.3 billion, and out-year gaps grew to as much as $16.8 billion in fiscal year 2028, the last year of the financial plan. After several key actions the Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2025 is balanced in the General Fund, as is required by law. However, projected out-year gaps, while smaller, persist—ranging from $5.0 billion in fiscal year 2026 to $9.9 billion in fiscal year 2028. (See Table 3.) Those key actions to balance the General Fund are:

-

Cash management actions: The Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Budget Financial Plan identified $2.2 billion in additional resources from fiscal year 2024 to be used to pre-pay costs in the next two years. Additionally, the Executive Budget discontinued out-year pre-funding for the Labor Settlement Reserve, reducing out-year gaps by $1.5 billion annually.5 Finally, $1.5 billion in available unspent funds was rolled from fiscal year 2027 to be used in fiscal year 2028.6 Through these actions, budget gaps are significantly reduced over the life of the financial plan before any other forecast changes or policy actions;

-

Tax receipts re-estimates: The Executive budget did not include significant broad-based tax increases but raised the tax receipts forecast significantly.

-

School aid savings: Three major policy proposals in the Executive Budget would moderate the rate of spending growth in school aid, providing recurring savings over the financial plan; (See below for additional detail and analysis.)

-

Medicaid forecast revision and savings: The Executive Budget significantly raised the Medicaid spending forecast—by nearly $3 billion annually in the out-years—due to enrollment trends, accelerating utilization of certain services, and the nonfederal costs of the recently approved federal redesign waiver. In response, the Executive proposed savings initiatives that would offset a majority of the higher spending; and (See below for additional detail and analysis.)

-

Migrant and asylum seeker services and supports: Total State spending on support and services would rise to $4.3 billion over a three-year period, including $2.4 billion added in the Executive Budget. About half of the spending is direct support for New York City. The remainder goes to covering rental costs of shelter sites, National Guard costs, legal services, health care, and other expenses.

Structural Imbalance

While the projected gaps of $5.0 to $9.9 billion are concerning, the State’s structural imbalance is much larger. The State continues to benefit from significant non-recurring resources to narrow current year and out-year gaps. Temporary tax surcharges in corporate taxes will expire after 2026 and in personal incomes taxes after 2027. The State also rolled $1.5 billion in available funds from fiscal year 2027 to fiscal year 2028 (described above) to help narrow the fiscal year 2028 gap. Finally, the State has already made debt service pre-payments of $2 billion in fiscal year 2028, using the fiscal year 2023 closeout surplus.7 Taken together, the $9.9 billion gap would be at least $6.4 billion greater if not for the use of these non-recurring resources. In other words, the structural imbalance—the gap between recurring resources and recurring spending—is $16.4 billion. (See Figure 1.)

Spending Growth

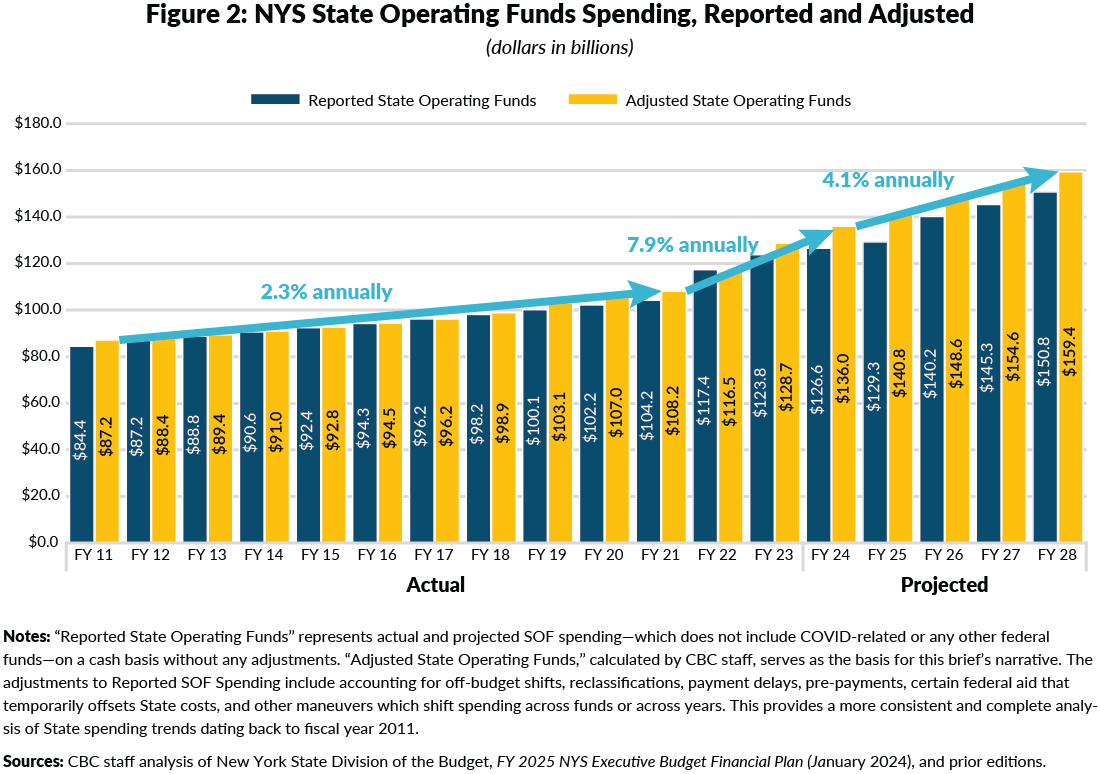

The Executive Budget included significant savings proposals, primarily in Medicaid and school aid. However, spending growth remained at an elevated level.8 Over the past three fiscal years, State Operating Funds (SOF) spending (after adjustments for payment timing, pre-payments, off-budget shifts, federal aid offsets, and other maneuvers) grew at an average annual rate of 7.9 percent. Over the life of the financial plan, SOF spending is set to grow at a rate of 4.1 percent annually. (See Figure 2.) Without the Governor’s savings proposals, SOF spending would grow 4.9 percent annually, a rate well beyond projected tax receipts growth and underlying economic indicators, such as personal income.

Based on current forecasts, significant spending restraint beyond the Executive Budget proposals will be needed to close projected budget gaps and the structural imbalance. If SOF spending were held to 2.0 percent annually over the life of the financial plan, the structural imbalance would be erased by fiscal year 2028, while allowing temporary tax increases to expire.9

Fiscal Management and Budget Process

Strong fiscal management policies and budget processes are key to making the best policy decisions. The Executive Budget proposed to grant considerable, fiscally risky power to the Executive. Many of these provisions are repeated from prior years, and most of them stem from the desire at the onset of the COVID pandemic for cash management flexibility. Today they instead create fiscal risk.10 These provisions include:

- Universal appropriation transfer and interchange authority within the State Operations bill;

- Permanent authority to issue up to $4 billion in short-term revenue anticipation notes;

- A $1 billion transfer from the General Fund to the “Health Care Transformation Account;"

- Provisions within individual appropriations that remove competitive bidding requirements and the Comptroller’s oversight;

- A "Special Emergency Appropriation" of $2 billion; and

- Limitations on the scope of Comptroller review of certain bond transactions.

Few changes have been made to the budget process over the past 15 years, despite ample opportunities for improvement. On the positive side, the Executive, Legislature, and Comptroller completed the Quick Start budgeting process for the third consecutive year, and oversight authority was largely restored to the Comptroller through legislation last year. Still, improvements to transparency, accountability, oversight, and fiscal management have not been made. Good-government groups outlined six simple actions to take immediately to improve the budget process, most of which have been ignored.11

Financial Plan and Fiscal Management Recommendations

- Restrain SOF spending growth, ideally to 2.0 percent annually: Limiting SOF spending growth to 2.0 percent annually would close the $9.9 billion projected budget gap, allow temporary tax increases to expire, and accommodate the exhaustion of non-recurring resources;

- Reject extraordinary Executive budget powers: Extraordinary Executive budget powers only serve to create fiscal risk, and they reduce accountability and oversight in the budget process. All of these should be omitted from the Fiscal Year 2025 Enacted Budget;

- Publish basic financial plan tables with the one-house and enacted budgets: New Yorkers deserve basic transparency in the spending plans put forward by the Executive and Legislature. One-house budget proposals should be accompanied by basic financial plan tables that allow spending plans to be compared with the Executive Budget. At the time of the enacted budget agreement, that same set of tables should be published to foster understanding of the budget agreement. Without such tables, the public and press are left to wonder whether legislators are advancing a budget without this basic information or choosing to withhold it from public view; and

- Pursue comprehensive budget process and fiscal management reforms: The Legislature and Executive should take additional, simple steps immediately to improve the budget process, including fully funding oversight agencies, avoiding the use of messages of necessity, and including fiscal impact statements with non-budget bills.12 To inform larger, long-term budget process reforms, the Legislature should hold a hearing this year to solicit additional options for budget reform.

Reserves

The State’s recent progress, spearheaded by Governor Hochul, in bolstering its principal reserves—both in size and structure—is its most significant fiscal management achievement in many years. Paltry reserves of $2 billion in 2020 have grown to $20 billion today. However, those reserves are not as large or protected as they should be.

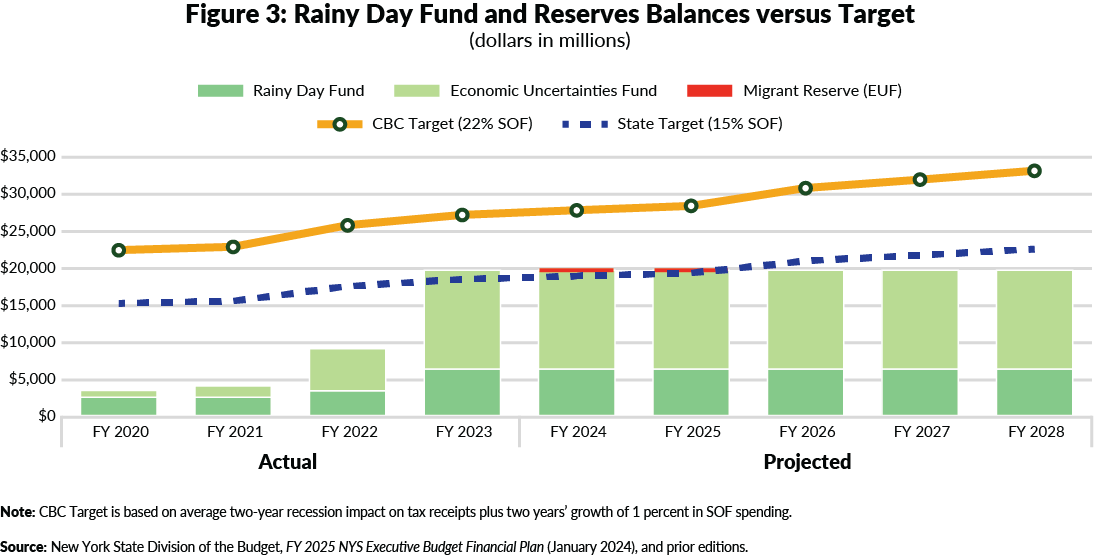

Today, principal reserves stand at $20 billion (including $500 million intended for migrant costs in fiscal year 2026), in line with the Executive’s target of 15 percent of SOF spending. However, CBC estimates that approximately $28 billion would be needed to meet the target standard: the ability to withstand two years’ recessionary receipts losses plus the ability to finance two years’ growth of 1 percent in SOF spending. (See Figure 3.)

Furthermore, more than two-thirds ($14 billion) of the total principal reserves balance is maintained in the Economic Uncertainties Fund (EUF)—a non-statutory fund with no restrictions on its deposits, balance, withdrawals, or replenishments. The vast majority of the State’s reserves can be drawn down under any circumstances at any time, putting the State’s rainy day savings at unnecessary risk. Conversely, the Rainy Day Reserve (RDR) and Tax Stabilization Reserve (TSR) are statutorily protected funds with secured balances that can be used only under specific circumstances.13

Reserves Recommendations

-

Deposit additional closeout balances to the RDR: If additional receipts are realized during the closeout of fiscal year 2024, the balance should be deposited to the Rainy Day Reserve;

-

Transfer the full balance of the EUF to the RDR: The State has sufficient capacity to immediately transfer the full balance of the EUF to the RDR. This would protect the reserved funds for use only in a catastrophe or economic downturn;

-

Set a target for the RDR to 22 percent of SOF spending: The State’s current goal of 15 percent is sound, but does not reflect the volatility of the State’s resources. A target of 22 percent (approximately $28 billion currently) is needed to cover two years’ receipts losses and spending growth;

-

Increase the maximum allowed RDR balance to 30 percent of SOF spending: Under current law, the balance of the RDR is capped at 25 percent of General Fund spending. However, the basis of the RDR balance cap would be more appropriately tied to SOF rather than the General Fund because it is a more comprehensive measure of State spending. Further, the cap should be raised to allow at least 22 percent SOF in reserves; and

-

Mandate automatic RDR deposits when the economy is growing: The main reason that State’s reserves were minimal prior to COVID is that the State chose not to make deposits. Sound fiscal management dictates that the State make deposits while the economy is growing so that it can use the balance when the economy is struggling. If the State mandates deposits in an expanding economy, the balance would be built when times are good.

Medicaid

Medicaid is by far the largest program in the State budget, comprising roughly one-third of spending. The program is undergoing a period of transition: Federal enhanced funding, enrollment changes, and maintenance of effort requirements in place from the onset of COVID have expired; the State recently received waiver approval to reinvest $6 billion in federal funds for system reforms; and the Governor’s Commission on the Future of Health Care (CFHC) is now working to provide by the end of 2024 a first round of reform recommendations.

However, the State’s immediate challenges come with rapidly rising costs. The Executive Budget updated the Medicaid spending forecast to account for elevated enrollment and utilization patterns. There are more Medicaid enrollees, and they are using more and costlier services than previously projected. Enrollment forecasts were increased based on actual enrollment data, and the State is now anticipating that Medicaid enrollment in 2024 will be approximately 600,000 higher than pre-pandemic levels. Elevated enrollment is not wholly unexpected. Actual enrollment is higher than the State’s projection that 1.3 million enrollees would leave Medicaid following the expiration of federal pandemic-related rules covering continuous enrollment.14 Outside of enrollment, the Executive Budget cites minimum wage increases, long-term care services, and payments to financially distressed hospitals as cost drivers.15

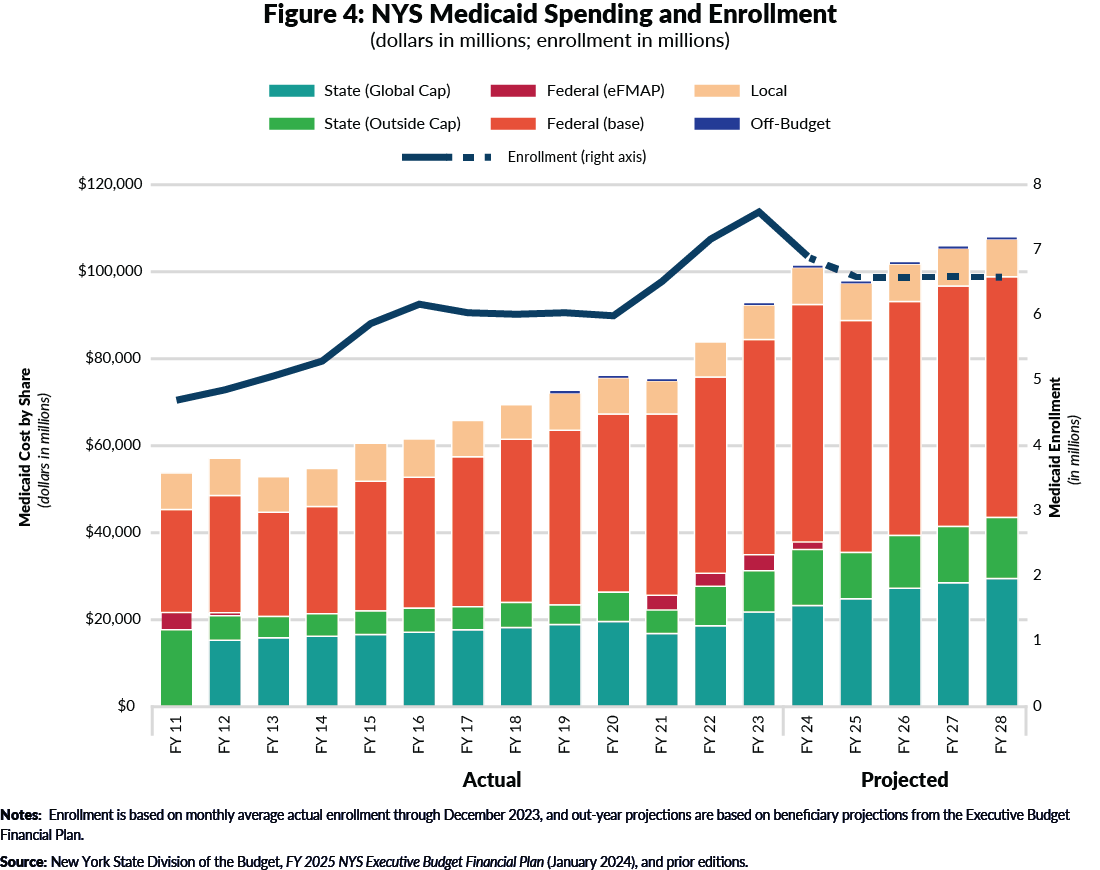

Without savings, Medicaid costs would far exceed the State’s Global Cap on Medicaid spending and exacerbate budget gaps.16 The Executive Budget proposed a comprehensive savings plan to offset most of the rising costs. Major policy changes to restrain spending growth include wage policy changes for the consumer-directed personal assistance program (CDPAP), across-the-board reductions to managed care rates on health plans, and many other actions impacting all categories of service. Even with the savings plan, the State share cost of Medicaid is slated to grow at 7.0 percent annually from fiscal year 2025 to fiscal year 2028. Including local, State, and federal funds, Medicaid spending will exceed $100 billion this year, and will push far beyond that benchmark in the out-years. (See Figure 4.)

Medicaid Recommendations

- Identify savings that maintain quality services to those in need: The State cannot sustain spending growth of 7 percent annually in its largest program. If the Governor’s savings proposals are rejected, the State will exceed the Global Cap spending limit and growth will be even greater than 7 percent;

- Manage Medicaid spending within a stronger Global Cap: The Medicaid Global Cap is neither global nor a cap. It is not global because approximately one-third of State Medicaid spending is not subject to the Cap because spending is outside of the Department of Health or otherwise exempt. It is not a cap because the State has used payment lags and delays to adhere to targeted spending levels.17 To be effective, the Global Cap should apply to all State share costs, and prevent uses of fiscal gimmickry to comply.

- Focus on accelerated growth areas such as long-term care and home- and community-based care: Savings should focus on areas of unsustainable cost growth, including in certain long-term care services such as CDPAP. The Budget Director recently stated that CDPAP costs have grown 1,200 percent in the past decade;18

- Require Commission to issue long-term cost savings recommendations this year: The Governor’s CFHC includes national and state experts in health policy and planning. Its expertise and independence could allow it to provide significant, innovative recommendations to improve the health care system and public health policy. However, it has no statutory mandate, or defined scope of work. The Commission’s stated first priority is to deliver a set of actionable recommendations that can drive improvement and savings in next year’s budget.19 The Governor and Legislature should ensure that those recommendations are delivered and be prepared to use them in next year’s budget; and

- Improve Medicaid data reporting to inform further savings: The size and rise of the State’s Medicaid program, unfortunately, has not come with more transparency. CBC outlined a plan to improve Medicaid data reporting during the Medicaid Redesign Team’s public forums in 2020.20 Four simple improvements should be made to bolster Medicaid data transparency, which can then be used by the civic community to recommend further program improvements:

- Amend required Global Cap Updates to be Medicaid Updates: State law requires the Department of Health to publish quarterly updates on Medicaid “Global Cap Report” spending, outlining projections for spending within Global Cap limits and other supporting information. The scope of these reports, however, is too limited. Data should be added to the spending of federal and local funds, in addition to the State share. Data should also include all State agencies. Total spending, utilization, and unit costs should be disaggregated by category of service. Spending detail from supplemental payments should also be included.21 Enrollment type and cost data should also be added (such as in the “Medicaid Statistics” page which was abandoned after 2013);22

- Publish Medicaid Updates in a timelier fashion: The Global Cap Reports are required to be published in a “timely” fashion. Unfortunately, current practice is for the reports to be released at least several months after the reporting period. For example, the report covering January to March 2023 was posted in August 2023, and zero reports have been posted for the current fiscal year, which is three-quarters complete. Global Cap reports used to be required monthly, but State law was changed to make them quarterly, apparently to reduce the administrative burden of preparation.23 Yet releases still suffer from extensive delays;

- Restore prior Medicaid presentation in the financial plan: For several years, the State financial plan section covering Medicaid included a comprehensive, multi-year table summarizing Medicaid spending. That table has been omitted from the financial plan and replaced with a more disjointed presentation that also omits key information. For example, the total local share is no longer published for out-years; and

- Publish the data and work of the CFHC: The recently convened CFHC is expected to provide research and policy ideas on health care overall, not just Medicaid. Still, its work will be “evidence-based” and presumably rely on extensive data.24 To the extent that the CFHC utilizes new data for its work, this supporting information should also be published.

School Aid

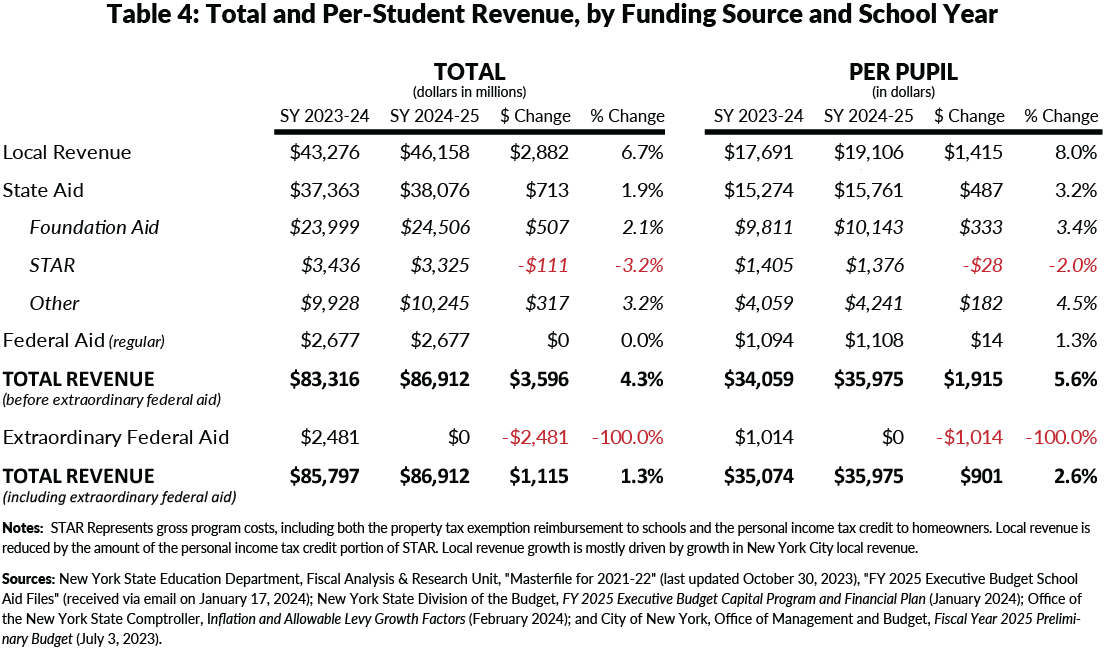

In the Executive Budget, school aid continues to grow in the out years. From school year 2020-21 to school year 2023-24, State school aid increased by $6.4 billion, or 26.1 percent. Going forward, from school year 2023-24 to school year 2027-28, State school aid would grow $4.0 billion further (10.7 percent). By any measure, State school aid has grown massively, and it would continue to grow steadily going forward.

Out-year growth in State school aid is more moderate in the Executive Budget proposal relative to current law, with multiple proposed adjustments to the State’s school aid formulas, specifically the Foundation Aid formula, which would reduce the rate of year-to-year growth. The key changes are:

- Phase Out of Hold Harmless: The Executive Budget proposed phasing out the hold harmless provision over two years. Under current law, hold harmless prevents year-to-year decreases in Foundation Aid in districts with declining enrollment or higher wealth and has been in place since 2007. The hold harmless provision is not fiscally sustainable;

- Change the Annual Inflation Factor: The Executive Budget proposed changing the annual inflationary growth factor in Foundation Aid from a single-year value to a 10-year average (excluding the highest and lowest years). This would reduce the inflation factor for the upcoming school year from 4.1 percent to 2.4 percent; and

- Modify the State Sharing Ratio: The State Sharing Ratio approximates a district’s reliance on State school aid. Wealthier districts tend to have a lower value, and districts with fewer local resources tend to have a higher value. Under current law, the State Sharing Ratio for all districts is capped at 0.90. The Executive Budget raised this cap to 0.91 in the 2024-25 school year. This results in some higher-need districts (63) receiving slightly more aid than they otherwise would have.

Taken together, the actions provide $413 million in State savings in school year 2024-25. Under the proposal, 337 districts would receive a year-to-year decrease in Foundation Aid. Importantly, the districts receiving year-to-year reductions tend to be wealthier districts. For example, 53 of the 68 wealthiest districts in New York would receive a reduction.25 Of the 337 districts receiving less funding, 101 are “self-funding” districts that fully fund a sound basic education without any State aid.

The adjustments made in the Executive Budget begin to address two issues in the State school aid spending. First, the State doesn’t sufficiently target aid; it directs substantial funds to high-wealth, low-need districts that can and do generate significant local funding. For example, among districts outside of New York City, the top 10 percent of districts by wealth generate more funding per student from local resources alone than average funding per student from all sources in all other districts. Second, the rate of growth in State school aid is not sustainable. Like Medicaid, State school aid has been growing at a rate far greater than other areas of the budget and more than tax receipts and tax base to support it. Prior to the Executive Budget, State school aid was set to grow 4.4 percent annually.26

It is important to keep in mind several facts about State school aid proposed in the Executive Budget:

- State aid has grown 26 percent over the past three years;

- State aid will increase every year going forward, by an average of 2.6 percent annually;

- State aid will grow 1.9 percent next year;

- State aid per student will increase 3.2 percent next year because enrollment is decreasing;

- Elimination of hold harmless will help the State direct additional resources to places and districts where needs and enrollment are growing; and

- Even with these improvements, the State will send $2.4 billion to 145 districts that fully fund a sound basic education before receiving any State aid.

School Aid Recommendations

- Eliminate hold harmless: CBC has advocated to eliminate the hold harmless provision for many years. The bottom line is: Hold harmless prevents aid from flowing to where needs are high and growing. A two-year phase-out is reasonable and will help the State better target its resources while providing recurring savings to help narrow budget gaps.

- Enact additional savings through inflation or other options: The inflationary factor adjustments yield savings, but other options would provide savings that are more targeted based on district need, including changing the allocation of expense-based aids to needs-based or the elimination of the School Tax Relief (STAR) program. Both expense-based aids and STAR are poorly targeted. STAR’s benefits are tilted more toward high-wealth districts; on average, STAR costs $1,885 per student in districts of above average wealth compared to $1,355 per student in districts of below average wealth.

- Improve school performance with measurement and management: The State’s spending on schools and education far exceeds that of any other state, and approaches double the national average on a per-student basis. New York is not posting nation-leading academic performance.27 Closer performance measurement and management should help increase academic achievement for all students and districts; the State should also assess whether $11.4 billion in federal aid passed directly to districts helped lessen pandemic impacts.28

Housing

The lack of housing production and affordability in New York State—especially in and around New York City—is at a crisis level and has been for many years, especially in downstate regions.29

Last year, the Governor’s Housing Compact proposal would have made New York a national leader in boosting production and affordability of housing of all types. Unfortunately, the proposal was rejected by the Legislature.

This year, the Governor’s housing proposals are far more targeted but still significant. The proposals are largely non-fiscal, geographically limited to New York City, and in line with those requested by New York City Mayor Eric Adams. These include proposals to:

- Raise floor area ratio (FAR) cap: This proposal would allow the City of New York to increase the FAR cap through a zoning resolution. It would also allow New York State Empire State Development to use general project plans for higher density within New York City;

- Facilitate office-to-residential conversions: New York State Department of Homes and Community Renewal would be authorized to establish a tax credit program through December 2031. The affordability thresholds are set by law, with at least 20 percent of units affordable at 80 percent of area median income and 5 percent of units at 40 percent of area median income.

- Legalize basement apartments: Changes are proposed to the multiple dwellings law to allow for legal conversions of basements and cellars to apartments;

- Extend 421-a deadline: This proposal extends the eligibility deadline for 421-a benefits to projects already in the pipeline in June 2022, with benefits extended through June 2031; and

- Replace 421-a with 485-x: The new proposed replacement of 421-a is dubbed “Affordable Neighborhoods for New Yorkers Tax Incentive Program.” The proposed statute outlines the terms of tax incentives, including 40-year exemptions for income-restricted homeownership projects and 35-year exemptions for rentals. The specifics on affordability and wage requirements are deferred to agreements to be made by other parties. New York City Department of Housing Preservation & Development would set affordability thresholds through regulation, and construction wage requirements would be established by a memorandum of understanding between a real estate trade group and construction unions.

In addition to the New York City-focused policies, the Executive Budget also proposes a capital program to develop housing and other amenities on State-owned properties. The Executive Budget appropriates $250 million initially (with expectations of future appropriations to grow to $500 million) to support a goal of developing 15,000 housing units on State-owned property across the State.30 The Executive specifically identifies three sites on Long Island, but additional sites across the State are expected to be utilized.

Housing Recommendations

- Enact a 421-a successor: Tax incentives are necessary to make affordable rental housing development in New York City financially feasible. Data continue to reflect that housing production—which was already too low with 421-a— has slowed to a crawl.31 Rising costs, high taxes, and stiff regulations continue to limit production, but a sound 421-a successor would help boost production of all types of housing;32

- Enact housing production and density improvements: Proposals to raise the FAR cap, support office-to-residential conversions, and legalize basement apartments would also help boost production and affordability; and

- Reject proposals that disincentivize production: Of equal importance to opening the flow of new housing production is to avoid proposals that would add counterproductive burdens to housing production and affordability. Additional onerous requirements and wasteful uses of public resources would exacerbate the housing crisis.

Additional Executive Budget Proposals and Recommendations

Retiree Health Benefit Cost Reform

The Executive proposes eliminating reimbursement for retiree and dependents’ Medicare Part B premium Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount (IRMAA) costs, an additional charge to recipients with qualifying incomes in excess of $103,000 annually.33 The elimination would provide savings of $24 million in the first full year of implementation.34

IRMAA is just one small piece of the total cost of financing retiree health care or other postemployment benefits (OPEB). The current OPEB liability totals $67 billion.35 The liability is significant and essentially unfunded. Unfunded OPEB liabilities present both a fiscal risk and a fiscal unfairness: Current taxpayers are financing OPEB costs for retirees who worked years ago, and future taxpayers will be paying OPEB costs for retirees who are working today. Ideally, OPEB costs should be funded as the obligation is incurred. That means setting aside funding to pay for OPEB costs while the employee is earning the benefit. However, the State only recently established a reserve to begin setting aside funding for OPEB costs.

It is fiscally prudent for the State to begin reducing its OPEB costs and liabilities. Elimination of IRMAA reimbursement has been proposed multiple times before, generally in concert with other reforms. Specifically, prior versions of the IRMAA elimination were paired with proposals to freeze Medicaid Part B premium reimbursement and to establish a tiered cost-sharing system for future retirees.36

Sales Tax Capture for Distressed Provider Assistance Account

As part of the Fiscal Year 2021 Enacted Budget, New York State began intercepting $250 million annually from sales tax receipts of local governments—$200 million from New York City and $50 million from all other counties. Two years later, the capture from counties was discontinued, and the amount from New York City was reduced to $150 million. The collected funds were set aside in the Distressed Provider Assistance Account, and funds are intended to be distributed to health care providers with acute financial needs.37 This year’s Executive Budget proposes extending the intercept for New York City an additional three years, through fiscal year 2028.

Fare and Toll Enforcement

The Executive Budget includes a three-part plan to increase enforcement of fares on Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) systems, tolls on State road and bridge authorities, and fees from the forthcoming congestion pricing system:

- MTA fare enforcement:

- Increases penalties for violations and failure to appear for summons;

- Allows for warning on first-time offense and waiving of fines for those enrolling in Fair Fares; and

- For second-time evaders, allows the MTA to distribute fare cards equal to half the paid fine amount; - Toll enforcement:

- Disallows sale of devices obscuring plates;

- Imposes a fine of $100 to $500 for intentionally obscuring plates at toll-collection point;

- Raises minimum fine for obscured plates to $250 and allows law enforcement to confiscate obscuring devices; and

- Prevents registration renewals on vehicles with suspensions for failure to pay tolls; and - Congestion pricing fraud enforcement:

- Sets various penalties for fraudulently obtaining and using credits, exemptions, or discounts.

Farebox and toll revenues are a key revenue source for all the State’s transportation authorities. Reliable collections of these user fees support operation and maintenance of the systems and make them reliable for riders today and into the future. Evasion and scofflaw activity diminish the financial condition of those systems and undermines the basic fairness and public support of important tolling programs.

Recommendations

- Enact OPEB reforms: The IRMAA cost elimination should be enacted to provide recurring savings. Furthermore, the budget should also include prior proposals to freeze Medicare Part B premiums and create a tiered cost-sharing system for future retirees, which would significantly reduce annual costs and the growing unfunded OPEB liability;

- Reject the NYC sales tax capture: The State should not foist its costs onto local governments, and the continuation of the sales tax capture unreasonably harms the City’s budget; and

- Enact proposed fare and toll enforcement policies: The State’s transportation authorities all rely on user fees—fares and tolls—to sustain their operations and pay for capital projects. Enforcement mechanisms to protect that critical revenue base are fair and fiscally necessary.

Conclusion

New York State’s fiscal challenges are real and significant, but also manageable. Continued strength in the economy has improved the tax receipts outlook for the State, but improving tax receipts are not and will not be the entire solution to closing out-year gaps. Restraining spending growth to 2.0 percent annually over the next four years would close the projected gaps and the structural gap and allow temporary tax increases to sunset. Failing to implement savings—especially in Medicaid and school aid—means unsustainable spending growth and much harder fiscal decisions in the near future.

Footnotes

- Gaps peaked in the Fiscal Year 2024 Enacted Budget Financial Plan. In July 2022, receipts were revised downward “in recognition of a weaker economic outlook for both the US and State.” Then in January 2023, they were revised downward again on expectation of an imminent “mild recession.” Finally, receipts were brought down further in June 2023 based on “weakness” in actual personal income tax collections. New York State Division of the Budget, First Quarterly Update to the FY 2023 Enacted Budget Financial Plan (July 2022), p. 8, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy23/en/fy23en-fp-q1.pdf, Fiscal Year 2024 New York State Executive Budget Financial Plan (February 2023), p. 13, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy24/ex/fp/fy24fp-ex.pdf, Fiscal Year 2024 Enacted Budget Financial Plan (June2023), p 10, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy24/en/fy24en-fp.pdf.

- See Table 1. These values do not include changes to miscellaneous receipts and deposits of the pass-through entity tax.

- New York State Division of the Budget, Fiscal Year 2024 Enacted Budget Financial Plan Mid-Year Update (October 2023), pp. t-3 to t-6, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy24/en/fy24en-fp-myu.pdf.

- New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2025 Economic and Revenue Consensus Report (March 1, 2024), www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/supporting/forecast/fy25/fy25-consensus-report-memo.pdf.

- The Labor Settlement Reserve is an informal reserve fund maintained to accommodate additional costs from new contracts. Because the State has recently agreed to multi-year contracts with its largest unions, those costs are accommodated in the financial plan and additional deposits are discontinued. New York State Division of the Budget, FY2025 NYS Executive Budget Financial Plan (January 2024), pp. 27 and 61, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy25/ex/fp/fy25fp-ex.pdf.

- In the Mid-Year Update, the financial plan reflected use of $1.5 billion from undesignated fund balance for gap-closing in fiscal year 2027. In the Executive Budget, the use of that balance is shifted from fiscal year 2027 to fiscal year 2028.

- New York State Division of the Budget, Fiscal Year 2024 Enacted Budget Financial Plan (June2023), p 15, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy24/en/fy24en-fp.pdf.

- Patrick Orecki, Excelsior! New York State Spending Growth Continues (Citizens Budget Commission, February 22, 2024), https://cbcny.org/research/excelsior.

- The 2.0 percent annual growth benchmark is based on assuming consistent SOF spending growth to $156.2 billion into fiscal year 2029, then reduced by $16.4 billion to account for the structural imbalance.

- Citizens Budget Commission and others, letter to Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins and Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie (February 20, 2024), https://cbcny.org/advocacy/watchdog-groups-urge-legislators-omit-extraordinary-budget-powers-one-house-proposals.

- Citizens Budget Commission and others, letter to Governor Kathy Hochul, Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, and Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie (January 19, 2023), https://cbcny.org/advocacy/groups-urge-leadership-implement-reforms-states-budget-and-fiscal-management-processes; and Patrick Orecki, New York State Budget Process Reform—Little Progress (Citizens Budget Commission, June 21, 2023), https://cbcny.org/research/new-york-state-budget-process-reform-little-progress.

- Messages of necessity are issued by the Governor to allow lawmakers to immediately vote on a bill, eliminating the three-day bill aging process and preventing public review before voting.

- Patrick Orecki, Making Hay While the Sun Shines (Citizens Budget Commission, June 28, 2023), https://cbcny.org/research/making-hay-while-sun-shines.

- New York State Department of Health, New York Public Health Emergency and Continuous Coverage Unwind Plan (February 16, 2023), p. 6, https://info.nystateofhealth.ny.gov/sites/default/files/NYSDOH%20Presentation%20-%20PHE%20and%20Continuous%20Coverage%20Unwind%20Plan%202-16-23.pdf; and New York State Comptroller, “Unwinding” Continuous Enrollment in Medicaid Presents Coverage and Financial Risks (January 4, 2024), www.osc.ny.gov/files/reports/pdf/medicaid-unwinding-financial-plan-risk.pdf.

- New York State Division of the Budget, FY2025 NYS Executive Budget Financial Plan (January 2024), p. 109, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy25/ex/fp/fy25fp-ex.pdf.

- The Global Cap limits allowable State share spending growth in Medicaid to a forecasted rate of expenditures growth calculated by the federal government, generally 5 to 6 percent annually. New York State Division of the Budget, FY2025 NYS Executive Budget Financial Plan (January 2024), p. 110, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy25/ex/fp/fy25fp-ex.pdf.

- Andrew Rein and David Friedfel, “Truth in (Financial Plan) Reporting” Citizens Budget Commission (November 5, 2019), https://cbcny.org/research/truth-financial-plan-reporting.

- Amanda D’Ambrosio, “Hochul eyes $6B CDPA program in efforts to cut Medicaid spending” Crain’s New York Business (February 16, 2024), www.crainsnewyork.com/health-pulse/kathy-hochul-looks-6b-cdpa-program-her-efforts-cut-medicaid-spending.

- New York State Governor Kathy Hochul, “New York State Commission on the Future of Health Care” (accessed February 28, 2024), www.governor.ny.gov/new-york-state-commission-future-health-care/new-york-state-commission-future-health-care.

- Public Comment of Andrew Rein, President, Citizens Budget Commission, before the Medicaid Redesign Team, Public Comment Submitted to the Medicaid Redesign Team II (March 2, 2020), https://cbcny.org/advocacy/public-comment-submitted-medicaid-redesign-team-ii.

- Public Comment of Andrew Rein, President, Citizens Budget Commission, before the Medicaid Redesign Team, Public Comment Submitted to the Medicaid Redesign Team II (March 2, 2020), https://cbcny.org/advocacy/public-comment-submitted-medicaid-redesign-team-ii.

- New York State Department of Health, “Medicaid Statistics” (updated November 2013), www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/statistics/.

- See Section 2 of Part A of Chapter 57 of the Laws of 2021.

- New York State Governor Kathy Hochul, “Governor Hochul Announces Launch of New Commission on the Future of Health Care” (Press Release, November 2, 2023), www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-launch-new-commission-future-health-care.

- These 68 districts reflect the top decile of wealthiest districts. Wealth deciles are based on the average of a district’s free and reduced-price lunch share and census poverty share, divided by the district’s combined wealth ratio as determined by New York State Education Department. The resulting figure is then indexed to the state average to determine a needs index.

- New York State Division of the Budget, Fiscal Year 2024 Enacted Budget Financial Plan Mid-Year Update (October 2023), p. 83, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy24/en/fy24en-fp-myu.pdf.

- Stevan Marcus, The Learning Ledger (Citizens Budget Commission, September 6, 2023), https://cbcny.org/research/learning-ledger.

- Testimony of Patrick Orecki, Director of State Studies, Citizens Budget Commission, submitted to the New York State Senate Committees on Education, New York City Education, and Budget and Revenue, Testimony on New School Aid Spending and Performance (October 5, 2021), https://cbcny.org/advocacy/testimony-new-school-aid-spending-and-performance.

- Sean Campion, Strategies to Boost Housing Production in the New York City Metropolitan Area (Citizens Budget Commission, August 26, 2020), https://cbcny.org/research/strategies-boost-housing-production-new-york-city-metropolitan-area.

- New York State Governor Kathy Hochul, “Governor Hochul Announces Next Phase in Long-Term Housing Strategy Will Focus on Increasing Housing Supply in New York City” (Press Release, January 9, 2024), www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-next-phase-long-term-housing-strategy-will-focus-increasing-housing.

- Real Estate Board of New York, Foundation Permit Report - January 2024 (February 20, 2024), www.rebny.com/reports/foundation-permit-report-january-2024/.

- Sean Campion, Amend It, Don’t End It (Citizens Budget Commission, March 15, 2022), https://cbcny.org/research/amend-it-dont-end-it.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “2024 Medicare Parts A & B Premiums and Deductibles” (October 12, 2023), www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/2024-medicare-parts-b-premiums-and-deductibles.

- New York State Division of the Budget, Public Protection and General Government Article VII Legislation Memorandum in Support (January 2024), p. 22, www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy25/ex/artvii/ppgg-memo.pdf.

- New York State Comptroller, State of New York Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2023 (September 2023), p. 168, www.osc.ny.gov/files/reports/finance/pdf/annual-comprehensive-financial-report-2023.pdf.

- Patrick Orecki, Budget Proposals with a Big Long-Term Payoff (Citizens Budget Commission, March 16, 2017), https://cbcny.org/research/budget-proposals-big-long-term-payoff.

- New York State Comptroller, “Distressed Provider Assistance Account” (accessed February 20, 2024), www.osc.ny.gov/local-government/data/distressed-provider-assistance-account.