Setting the Right Ceiling

Rethinking the City’s Debt Limits and Capital Process

SUMMARY

New York City has requested that the State raise the City’s debt limit—the maximum amount of the long-term debt the City can have outstanding—by $18.5 billion. The Governor has proposed instead to increase capacity by $12 billion. To ensure the City’s debt remains affordable while providing capacity to pursue critical capital projects, the Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) recommends the City and State proposals be rejected in favor of a two-factor approach: adoption of a lower limit indexed to the City’s economic capacity and the addition of a new limit to annual debt service to ensure other operating priorities are not squeezed out.

INTRODUCTION

Governments often issue long-term debt to finance capital projects. Since the immediate fiscal impact is only a fraction of the ultimate costs, jurisdictions typically set limits to ensure their long-term debt is affordable. These limits may set a maximum amount of outstanding debt, a maximum amount of debt service costs, or a combination of both factors, relative to an economic measure of the jurisdiction’s ability to repay the debt.

New York City is no exception. Its outstanding long-term debt, which finances its capital investments, is limited by both the New York State Constitution and State law. Debt of the New York City Transitional Finance Authority (TFA) is subject to the City’s Constitutional debt limit, except an additional $13.5 billion is allowed by State law (TFA Statutory limit).

At the City’s behest, Governor Kathy Hochul's Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Budget includes a proposal to increase New York City's debt limit. The City requested an $18.5 billion increase to the TFA Statutory limit, lifting it to $32 billion. The City asserts an increase is necessary to accommodate both currently planned and future capital commitments amid a narrowing debt capacity. Modifying the City’s request, the State Executive Budget proposed to increase the TFA Statutory limit $6 billion in each of the next two years—a cumulative $12 billion increase in debt capacity.

CBC recommends four criteria guide policymakers in setting the City’s debt limit:

- Ensure reasonable long-term affordability of outstanding debt;

- Require annual debt service payments remain affordable;

- Provide necessary capacity to fund important capital investments; and

- Incentivize capital investment discipline, including project prioritization and cost effectiveness.

Analyzing the proposed increase, CBC finds:

- Total personal income is the right capacity measure for the TFA Statutory limit, as it is the economic base used to generate revenue to repay the debt;

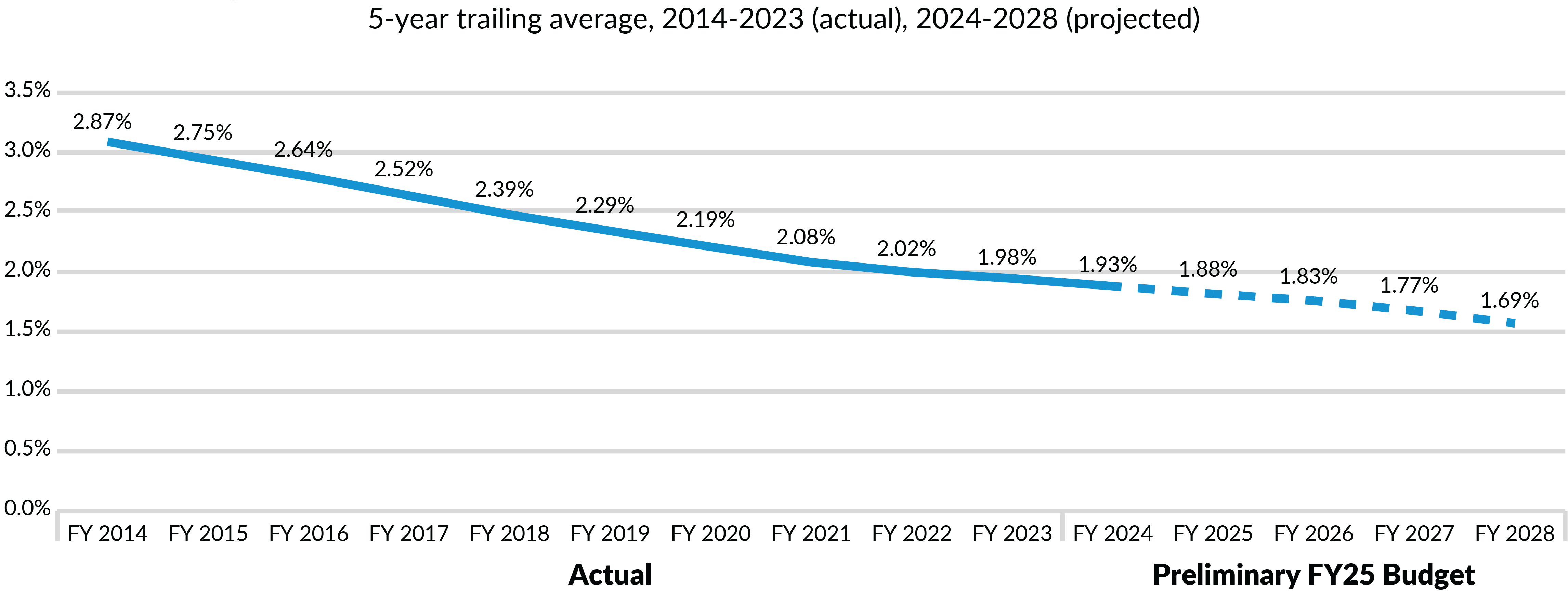

- The TFA Statutory limit has fallen from 3.3 percent of total personal income, when the cap was last raised, to 1.9 percent this year due to increasing personal income;

- Indexing the TFA Statutory limit to personal income would allow it to steadily increase, while providing predictability to facilitate comprehensive capital planning;

- The City’s request for an $18.5 billion addition to its debt capacity would raise the debt limit to 4.5 percent of personal income, higher than it has been in the past; and

- Even the Governor’s more modest proposal would bring the TFA Statutory limit to 3.5 percent, above recent levels.

To ensure the City’s debt remains affordable while providing capacity to pursue critical capital projects, CBC recommends the City and State reject the City and State Executive Budget proposals and instead:

- Index the TFA Statutory limit to 2.5 percent of total personal income, to ensure the City’s debt capacity grows with its underlying economic capacity;

- This will increase the TFA Statutory limit from $13.5 billion in fiscal year 2023 to $23.8 billion in fiscal year 2033;

- Formalize the City’s long-standing practice of keeping annual debt service costs below 15 percent of tax revenue, to protect its operating budget and credit ratings;

- Continuously and comprehensively improve how the City makes capital investments, including prioritizing projects, reducing costs, and streamlining project delivery; and

- Amend the Constitutional debt limit to be more holistic; it would be preferable to have one limit based on an appropriate economic metric that covers all City debt repaid with tax revenues.

BACKGROUND

To maintain an affordable level of outstanding debt, the New York State Constitution limits New York City’s outstanding debt. The debt limit—equal to 10 percent of the average full valuation of taxable real property in the prior five years—is meant align the City's debt burden with its ability to raise funds to repay it.1 According to the City’s most recent Annual Comprehensive Financial Report, the City held $96.9 billion in outstanding debt against a debt limit of $127.5 billion, leaving 24 percent, or about $30 billion, of remaining borrowing power.2

Additionally, State law permits the City to issue up to $13.5 billion in TFA bonds (TFA Statutory limit).3 The TFA was created by State statute in 1997 to allow the City to incur additional debt that was exempt from the Constitutional debt limit, initially up to $7.5 billion.4 The City pledges personal income tax (PIT) and sales tax revenue to repay TFA debt, referred to as Future Tax Secured (FTS) bonds.

The TFA Statutory limit has been increased multiple times, reaching $13.5 billion in 2006.5 In 2010, to permit the City to leverage the favorable, lower-interest market conditions for TFA, the State authorized the City to issue TFA debt above the TFA Statutory limit. Incremental debt above the Statutory limit, however, was subject to the Constitutional debt limit.6 At the end of fiscal year 2023, there was $45.6 billion of outstanding TFA debt: $13.5 subject to the TFA Statutory limit and the remaining $32.1 was subject to the Constitutional debt limit.7

The TFA was initially created in 1997 as a provisional vehicle for the City to issue a small amount of debt amid then-urgent concerns about an impending debt limit breach. Nearly 30 years later, the “transitional” TFA is likely permanent. It allows the City to tap revenue streams other than the property tax to support debt and is also very well-received in the municipal bond market.

New York City issues long-term bonds through other vehicles that are not subject to the Constitutional or TFA Statutory debt limits. Municipal Water Finance Authority bonds, TFA Building Aid Revenue bonds, and conduit debt are exempt and not covered in this report.

Additionally, the City has a policy to keep annual debt services payments, which are a component of the operating budget, below 15 percent of tax revenue to ensure that debt service costs do not unduly pressure the operating budget and crowd out other expenses.8 While this is a component of the debt management policy agreed to by the City Comptroller and the Mayor’s office, it is not formally codified and there are no enforcement mechanisms or consequences for breaching the cap.

PROPOSALS TO INCREASE THE TFA STATUTORY LIMIT

The City has requested to increase the TFA’s debt limit, stating concern that the available borrowing capacity will not be sufficient for planned and future capital projects. The current Capital Commitment Plan (CCP) can be accommodated within the existing limit. However, the CCP released in January 2024 did not include about $17 billion the City now says it plans to spend between fiscal years 2025 to 2031 on three major capital projects—the School Construction Authority’s 5-year capital plan, the construction of four new borough-based jails, and repairs to the City-owned portion of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Including these projects could push indebtedness beyond the debt limit around fiscal year 2028.9

The City has requested an $18.5 billion increase in the TFA Statutory limit, plus subsequent indexing of the limit to the annual percent increase in personal income tax (PIT) and pass-through entity tax (PTET) revenues.10 Gov. Hochul’s Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Budget proposed to increase the TFA Statutory limit by $12 billion over two years, without subsequent indexing, for a new Statutory limit of $25.5 billion by fiscal year 2026.11 Both the Assembly and Senate included the Governor’s proposal in their one-house budgets; the Senate included language that would require a portion of the increase to support debt for the City University of New York.12

FRAMEWORK FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEBT LIMIT

The debt limit should not merely be a function of the capital plan; debt affordability is more complex than ensuring there is adequate capacity for the current set of projects. Prior increases in the TFA Statutory limit have largely been set based on the additional capacity to fund planned projects, without also requiring a close examination of the capital plan.

Criteria to Balance Affordability and Need

Instead of periodically increasing the City's debt limit by arbitrarily determined, lump sum additions to the TFA Statutory limit, the City and State should pursue a more holistic approach that:

- Ensures reasonable long-term affordability of outstanding debt;

- Requires annual debt service payments remain affordable;

- Provides necessary capacity to fund important capital investments; and

- Incentivizes capital investment discipline, including project prioritization and cost effectiveness.

Since outstanding debt affects both the City’s long-term fiscal capacity and its annual budget, a comprehensive approach to the City’s debt limit would encompass both the amount of outstanding debt and the annual debt service cost. Outstanding debt should be measured relative to appropriate measures of the City’s economic capacity to carry and repay that debt, as the Constitutional debt limit now does. The Constitutional debt limit measures debt against the full value of taxable property, which undergirds the property tax. Annual debt service costs should be measured relative to the annual revenues used for repayment. This ensures that debt service is relatively affordable and does not squeeze out other operating budget priorities.

However, these should be balanced with the City’s need to have sufficient resources to maintain public infrastructure and invest in priority capital projects. The debt limit should be neither too tight as to inhibit important capital investment, nor too loose to allow for unnecessary or inefficient spending. The City should be able to invest in critical capital projects while being incentivized to prioritize projects, lower costs, and shorten project timelines.

INDEXING FOR SUSTAINABILITY

Indexing the TFA Statutory limit to total personal income in the City would strengthen its integrity and remove it from periodic political negotiations. Setting the TFA Statutory limit as an appropriate percent of the rolling five-year average of total personal income would smooth annual spikes or dips, while basing borrowing capacity on the underlying economic resource that generates the revenue used to repay TFA FTS debt.

Since PIT revenue is the primary source for repaying TFA FTS bonds, total personal income is the right economic measure to determine capacity, and therefore affordability. Indexing maintains affordability while ensuring debt capacity does not erode over time. The formula is also conceptually consistent with the rationale behind the Constitutional debt limit; both would limit debt based on measures of economic capacity, overall property values for the Constitutional debt limit and total personal income for the TFA Statutory limit.

Personal income is preferable to personal income tax revenue, as proposed by the City. Tax collections are a function of both the underlying economic base and public policy, the tax rate. Increases in personal income tax rates should not increase borrowing capacity because the underlying economic base—personal income—would not have increased.

Furthermore, to smooth out year-over-year fluctuations that could generate unpredictable spikes in additional borrowing capacity, the debt limit should be based on a rolling, five-year average.

History can guide how much TFA FTS debt outside the Constitutional limit the City can afford. Since 2010, the TFA Statutory limit has been $13.5 billion. The TFA Statutory limit, relative to five-year trailing averages of the City's total personal income, ranged from 3.3 percent in 2010 to 1.9 percent in 2024, with a 15-year average of 2.5 percent. (See Figure 1.) Based on OMB’s economic forecast, the current limit of $13.5 billion would be 1.7 percent of total personal income by 2028.

The City’s proposal to raise the TFA Statutory limit by $18.5 billion would increase the limit to 4.5 percent of the five-year rolling average of total personal income in fiscal year 2025, higher than past levels. The Governor’s smaller increase would still push the TFA Statutory limit higher than historical levels—3.5 percent of the five-year average in fiscal year 2026, when the full increase would take effect.

Figure 1: Current TFA Statutory Limit as Percent of Total Personal Income

City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2025 Preliminary Budget: Financial Plan Detail (January 16, 2024), https://www.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/tech1-24.pdf; Office of the New York City Comptroller, Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2023 (October 26, 2023), and fiscal year 2010 to fiscal year 2022 editions, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/annual-comprehensive-financial-reports/.

RECOMMENDATIONS

A holistic approach to debt affordability for the City should limit both the amount of outstanding debt and annual debt service payments. This two-pronged approach would ensure that the City can afford the debt, both annually and in the long run. Given that New York City, unlike many other cities, has diverse revenue stream sources in addition to its property values, it is reasonable to index part of the debt limit to personal income. Indexing also ensures that debt capacity align with the City’s underlying economic resources and generally grows to allow investment. This facilitates the capital planning process by eliminating one-off, negotiated increases that are hard to predict and not analytically grounded. Lastly, an amendment to the State Constitution to cover both GO and TFA FTS debt under one holistic debt limit using an appropriate economic measure would ensure that the full range of economic resources available to the City are considered when determining an affordable amount of outstanding debt.

Index TFA Statutory Limit at 2.5 Percent of Personal Income

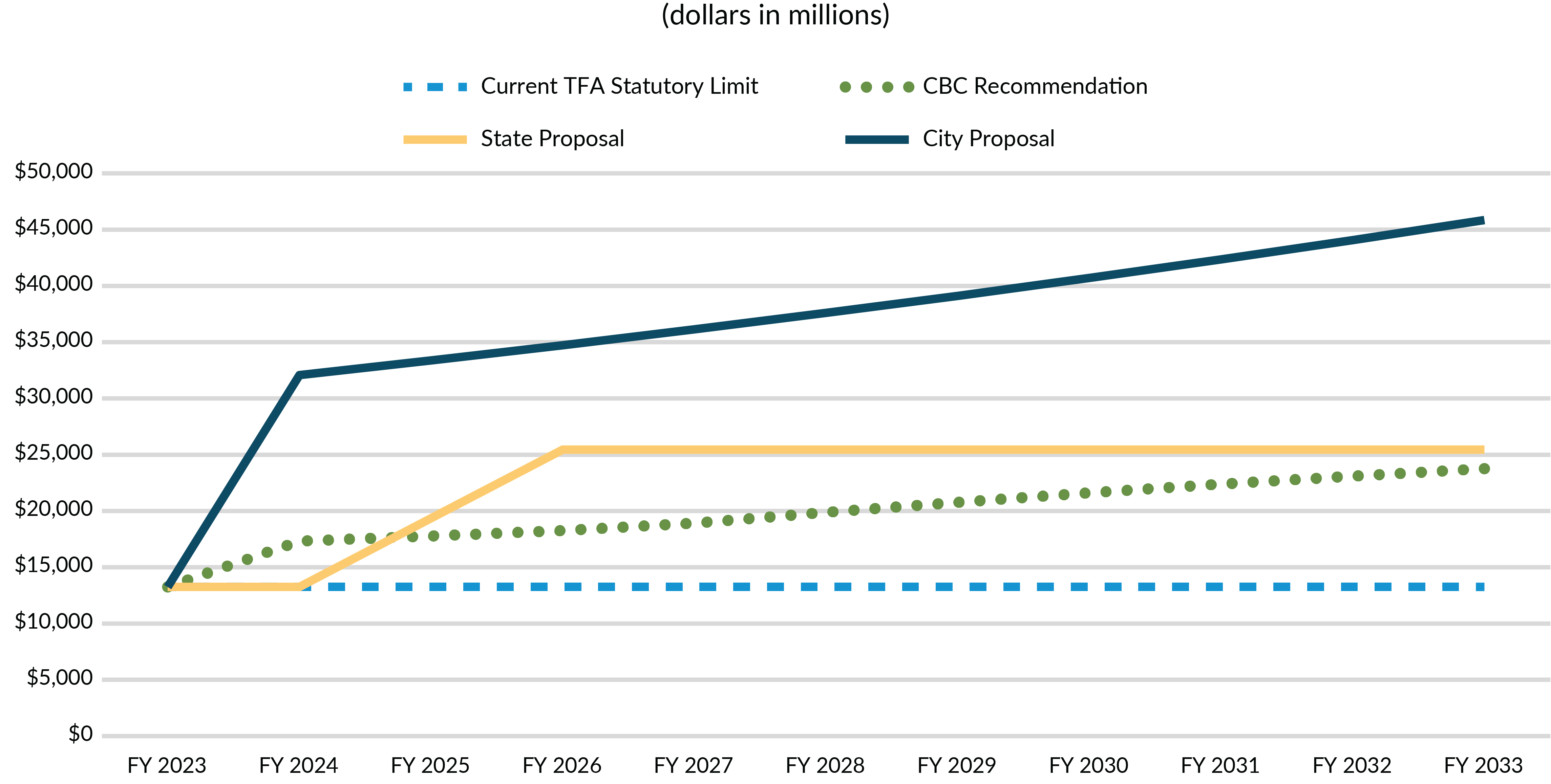

Based on history and the City’s need to both prioritize projects and contain costs, CBC recommends a TFA Statutory limit of 2.5 percent of total personal income. This would expand the City’s borrowing capacity immediately and subsequently allow capacity to grow gradually with personal income rather than expand abruptly with the two-year, $12 billion increase proposed by the Governor.

Indexing to 2.5 percent would add $4 billion in TFA FTS debt capacity by July 1, 2024. (See Figure 2.) By fiscal year 2030, when OMB projects the City to come closest to its debt limit, the City would have roughly $8.2 billion in additional debt capacity. Assuming a conservative annual growth rate for total personal income of 2.75 percent after fiscal year 2029, the TFA Statutory limit would reach $23.8 billion by fiscal year 2033, just $1.7 billion shy of the Governor’s current proposal. Stronger growth in personal income—a historical likelihood—would raise the TFA limit even higher.

This increase would allow the City to pursue its current capital plan without pushing up against its debt limit. However, if debt were incurred to fund the $17 billion in additional projects the City has identified but not yet incorporated into its plan, the City could breach the limit in fiscal year 2030 by $300 million.13 This may well mean that a higher index level should be considered. However, that determination is challenging given the lack of information or structured review of the plan.

Since indexing provides predictable increases, it can facilitate capital planning that is more thoughtful, disciplined, and prioritized; the right index increases the limit to an affordable level and creates the incentive to prioritize projects and reduce capital costs. If, following a comprehensive review of the capital plan, additional debt capacity provided by indexation is inadequate to deliver needed capital projects, the indexation level can be reevaluated and adjusted.

Figure 2: Projection of New TFA Statutory Capacity under Different Proposals, with Existing Limit

CBC Recommendation is to index TFA Statutory limit at 2.5 percent of personal income. State Proposal is to increase the TFA Statutory limit by $6 billion in FY 2025 and $6 billion in FY 2026. The City Proposal is to increase the TFA Statutory limit by $18.5 billion in fiscal year 2024, followed by indexing the limit to annual increase in personal income tax revenue, if any. Figure assumes personal income tax grows at 4 percent annually.

City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2025 Preliminary Budget: Financial Plan Detail (January 16, 2024); Office of the New York City Comptroller, Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2023 (October 26, 2023); and New York State Executive Budget FY 2025, Public Protection and General Government, Article VII Legislation, Part V (January 16, 2024).

Formalize Debt Service Limit at 15 Percent of Tax Revenue

The City’s guidelines and guardrails on debt service affordably are inadequate. The half-page section in the Debt Management Policy states: “The primary metric the City uses to determine debt affordability is that annual debt service as a percent of tax revenues should be no more than 15 percent.”14 While this 15-percent benchmark is acknowledged positively by rating agencies, it is only found in this policy negotiated by the Mayor and the City Comptroller.15 Given the importance of this target, it should be more formally adopted, with required actions should the City exceed the limit clearly identified.

Conduct a Comprehensive Capital Plan Review, Prioritize Projects, and Seek to Reduce Costs

The current City-funded capital plan is $152.2 billion ($156.8 billion overall) over 10 years and contains hundreds of capital projects, some of which have been included in the plan for years. The ability to pay for all these projects does not mean they are appropriate, necessary, or will be well managed. The City should review each capital project to determine if it is necessary and scoped and priced properly. Outdated estimates should be updated. Unnecessary projects should be dropped. The remaining capital projects should then be prioritized.

The City convened a Capital Process Reform Task Force in 2022 to review how procedures and applicable laws drive up the cost of capital projects.16 The Task Force issued recommendations, some of which have been implemented and others which are in progress. The City should continue to make procedural improvements within its power and lobby Albany for the necessary legislative and regulatory changes that would make capital planning and project delivery more efficient and effective.

Amend the Constitutional Debt Limit to Cover All Debt Repaid with Tax Revenues

The City’s TFA FTS debt and GO debt—collectively the primary financing mechanisms for the City's capital plan—are both effectively tax-secured obligations on the City that are repaid with the same City tax revenues, despite being secured by different tax revenue streams for finance and rating purposes. Currently, there are two separate limits that constrain the amount of outstanding GO and TFA FTS debt.

Therefore, the State should consider amending the Constitutional debt limit that applies to all tax-secured City-issued debt (this would not affect the debt limit of other municipalities in New York State). To consolidate TFA FTS and general obligation debt under a single debt limit, it would be necessary to identify the appropriate economic capacity metric—it could be a higher percent of the City's full valuation of real property, or it could be an alternative or blended metric that more appropriately measures the breadth of the City’s economy and diverse tax revenue sources. A holistic limit on all debt repaid with City tax revenues would further enhance the Constitutional limit's integrity and predictability.

CONCLUSION: ALIGNING DEBT, AFFORDABILITY, AND REVENUE

A substantial debt-capacity expansion not grounded in fiscal analysis and lacking key controls could threaten long-term debt affordability, the City’s high bond ratings, the ability to do effective capital planning, and other operating budget priorities.

The State should base the TFA Statutory limit on metrics that meaningfully relate to the debt’s source of repayment—in this case, total personal income in the City. The historical practice of granting arbitrary increases to TFA Statutory capacity on an ad-hoc, lump-sum basis is not fiscally sound. Rather, indexing the limit to the funds that are the revenue base for repayment would ensure a more enduring and responsive level of affordability.

Furthermore, any additions to TFA Statutory limit should be accompanied by a firmer codification or institutionalization of the 15-percent debt service affordability measure. The Office of the New York City Comptroller concurred in its fiscal year 2025 Preliminary Budget report, stating that the Governor’s “reasonable” increase to TFA capacity “should be accompanied by a City policy that ensures that debt service remains below the long-standing threshold of 15 percent of tax revenues.”17

However, even if the City can afford to take on more debt, it should do so judiciously, with an eye on the impact on future generations of New Yorkers. Public funds today and in the future should be used for necessary capital investments that are delivered cost effectively and tangibly improve the City’s infrastructure or quality of services. Projects in the current capital plan should be regularly assessed and prioritized, eliminating those that are not needed. Furthermore, the City should continue to seek procedural and legislative reforms to reduce capital costs.18

Finally, the City’s capital process remains a particularly dysfunctional and opaque corner of municipal operations, lacking several key hallmarks of good government: prioritization or clear rationale in project conception and planning; transparency to facilitate monitoring or accountability; and demonstrated efforts to contain costs or expedite project delivery. Additionally, the capital budget needs a clear prioritization of projects and the level and pace of capital commitments that is practical, attainable, and enforceable.19 Numerous monitors and oversight bodies have long advocated for the City to review its capital process comprehensively and holistically with an eye for prioritization and pragmatism, an issue that only grows in urgency with an impending increase in the City’s borrowing power.20

Footnotes

- New York State Constitution, Article VIII – Local Finances, Section 4 – Limitations on local indebtedness.

- City of New York, “Annual Comprehensive Financial Report of the Comptroller for the Fiscal Years Ended June 30, 2023 and 2022,” October 26, 2023 https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/ACFR-2023.pdf.

- New York State, Chapter 411 of the Laws of 2006.

- New York State, Chapter 16 of the Laws of 1997.

- New York State, Chapter 411 of the Laws of 2006.

- New York State, Chapter 182 of the Laws of 2009.

- This excludes Building Aid Revenue Bonds (BARBS), which are repaid with State building aid, and NYC Recovery Bonds, issued after the September 11 attacks, which were authorized under separate State law. The $32.1 billion is included in the $96.9 billion total debt subject the Constitutional debt limit. Office of the Comptroller of the City of New York, “Annual Report on Capital Debt and Obligations Fiscal Year 2024,” December 1, 2023 https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/annual-report-on-capital-debt-and-obligations.

- City of New York, “Debt Management Policy: New York City General Obligation and New York City Transitional Finance Authority,” September 1, 2022 https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/NYC-Debt-Policy-9.1.2022.pdf.

- Office of the Comptroller of the City of New York, “How Much Is Enough? Evaluating the Need to Increase the City’s Debt Capacity,” March 14, 2024 https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/How-Much-Is-Enough-Evaluating-the-Need-to-Increase-the-Citys-Debt-Capacity.pdf.

- The City’s proposal would only adjust the Statutory TFA limit upward in PIT and PTET revenues increase; if revenues decrease, the Statutory TFA limit would not change. Office of the New York State Comptroller, “Review of the Financial Plan of the City of New York,” Report 19-2024, February 2024 https://www.osc.ny.gov/files/reports/osdc/pdf/report-19-2024.pdf.

- New York State, “Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Budget: Public Protection and General Government, Article VII Legislation,” Part V.

- New York State Senate Budget, “Public Protection and General Government,” Part V, January 17, 2024.

- Based on the City Comptroller’s analysis of projected borrowing with an additional $17 billion in capital spending and CBC’s projected limit if the TFA Statutory limit was indexed to 2.5 percent of personal income, using the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget economic forecast. Office of the Comptroller of the City of New York, “How Much Is Enough? Evaluating the Need to Increase the City’s Debt Capacity,” March 14, 2024 https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/How-Much-Is-Enough-Evaluating-the-Need-to-Increase-the-Citys-Debt-Capacity.pdf; and City of New York, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, Preliminary Fiscal Year 2025 Budget: Financial Plan Detail (January 16, 2024), https://www.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/tech1-24.pdf.

- City of New York, “Debt Management Policy: New York City General Obligation and New York City Transitional Finance Authority,” September 1, 2022 https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/NYC-Debt-Policy-9.1.2022.pdf.

- For example, the manageability of the City’s relatively large debt burden is attributed to “compliance with a policy to maintain debt service costs below 15% of tax revenues, while another rating agencies credits “the city’s long-time target of maintaining debt service at less than 15% of tax revenue” for its AAA rating of TFA bonds. See: Fitch Ratings, New York City General Obligation, February 23, 2024; S&P Global Ratings, Transitional Finance Authority Future Tax-Secured Bonds, February 2, 2024.

- City of New York, “New York City Capital Process Reform Task Force: 2022 Year-end Report,” December 2022 https://www.nyc.gov/assets/home/downloads/pdf/press-releases/2023/CP_ReformTaskForce.pdf.

- Office of the Comptroller of the City of New York, “Comments on New York City’s Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2025 and Financial Plan for Fiscal Years 2024 – 2028,” March 4, 2024 https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/comments-on-new-york-citys-preliminary-budget-for-fiscal-year-2025-and-financial-plan-for-fiscal-years-2024-2028/.

- City of New York, “New York City Capital Process Reform Task Force: 2022 Year-end Report,” December 2022 https://www.nyc.gov/assets/home/downloads/pdf/press-releases/2023/CP_ReformTaskForce.pdf.

- Citizens Budget Commission, “Rightsizing and Right Timing New York City’s Capital Plan,” March 14, 2018 https://cbcny.org/research/rightsizing-and-right-timing-new-york-citys-capital-plan.

- Financial Control Board, “Staff Report: FY 2024 January Modification and Financial Plan,” March 6, 2024 https://fcb.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2024/03/fcb-staff-report-fy-2024-january-modification-and-financial-plan.pdf.