Sound Strategy, Sound Future

Recommended Approach for the City’s Preliminary FY 2020 Budget

Mayor Bill de Blasio will release the New York City Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2020 next week. A thriving economy has allowed the City to increase spending significantly—by $20 billion since fiscal year 2014—and expand the City’s workforce 12 percent to a record 332,000 full-time equivalent employees.1 Spending, particularly for new initiatives, has been balanced insufficiently with saving for a rainy day; budget reserves stand at $1.375 billion in fiscal year 2019. In addition, public authorities providing important housing, transit, and health services to New York City residents continue to be on shaky fiscal ground.

The Preliminary Budget presents an opportunity for the City to undertake the necessary course correction with a four-part strategy:

- Contain spending growth;

- Build reserves;

- Adapt the capital plan to a resource constrained environment; and

- Strengthen finances of public authorities.

This blog describes the key elements of this strategy and what to look for in the Preliminary Budget to assess whether the City is preparing adequately for more fiscally challenging times.

Contain Spending Growth

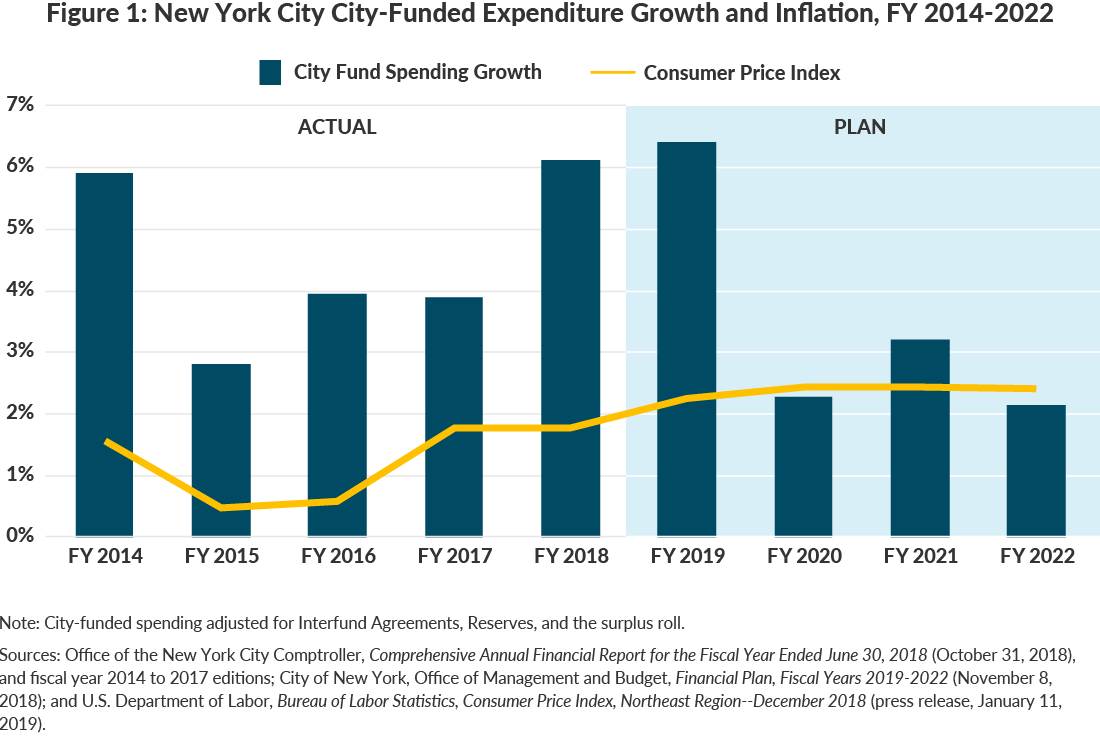

1. Limit spending growth to inflation: City-funded spending grew 6.1 percent in fiscal year 2018, more than three times the rate of inflation, and is projected to increase 6.4 percent in fiscal year 2019. An increase equal to inflation would limit the City-funded spending increases to 2.5 percent in fiscal year 2020.2 Achieving this will require restraint in hiring and a vigorous Citywide Savings Program.

2. Better management of personnel: Since half of the City’s expenditures are for personnel costs, reining in headcount growth is essential to bringing spending growth in line with inflation. From fiscal year 2014 to 2018, city government grew by 28,320 positions and is projected to grow by an additional 6,970 positions in the current year. No additional headcount should be authorized; improved productivity of existing personnel should accommodate new needs and initiatives. The City should also focus on managing personnel costs for current staff: Overtime spending continues at record levels, nearly $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2018, and should be reduced.

3. More rigorous savings program focused on efficiency: The Citywide Savings Programs (CSPs) include few savings from enhancing the productivity and efficiency of government operations. The Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) estimates efficiency measures comprise 14 percent of the cumulative savings since May 2015, the first CSP of the de Blasio Administration. Savings totaling 83 percent result from routine and important actions that the City takes as part of managing its finances—refunding debt service, updating spending estimates, and shifting expenditures to the State or federal government when appropriate.3 The CSP should generate recurring operational savings to fund fully any new or expanded programs and should be equal to at least 1 percent of City-funded spending, which would generate about $700 million per year, significantly exceeding previous efficiency savings efforts that have not exceeded 0.2 percent of City-funded spending.

Key Questions

- Does the proposed budget in fiscal year 2020 grow beyond the rate of inflation?

- Is the projected headcount in fiscal year 2020 greater than fiscal year 2019 and the previous fiscal year 2020 plan?

- Will the Citywide Savings Program feature a greater level or share of savings generated from efficiency measures?

- How much funding has been added for new initiatives such as NYC Care, NYC Ferry, and 3K; is it accompanied by additional headcount; and is it offset by efficiency savings?

Build reserves

When spending growth is contained, surplus revenues should be directed to build reserves needed to weather a recession, or reduce long-term liabilities.

1. Increase budget reserves: While the economy continues to grow, there are signs of softening; job growth is slowing, and the residential real estate market is sluggish. The City is not adequately prepared to weather a recession. The General Reserve and Capital Stabilization Reserve stand at $1.375 billion in fiscal year 2019. A recession, similar in scope to the previous three, could result in a revenue shortfall up to $16 billion, measured against the four-year financial plan.4 Spending should be reduced and budget reserves increased.

2. Make a deposit to the Retiree Health Benefits Trust (RHBT): The de Blasio Administration deserves credit for its commitment to increasing the trust’s size to a record $4.8 billion; however, annual deposits to the RHBT are typically made at the end of the year and were just $100 million in each of the last two fiscal years. The City should plan for annual deposits at higher levels in each year of the financial plan. The long-term unfunded liability for retiree health insurance and other postemployment benefits, not including pensions, is nearly $100 billion and represents a threat to the City’s long-term fiscal health.5

3. Reduce long-term liabilities: The City’s aggregate long-term liabilities reached $257 billion at the end of fiscal year 2018; surplus revenues can also be directed to paying off outstanding bonded debt, which totaled $111.0 billion at the end of fiscal year 2018.6

Key Questions

- Have reserves in fiscal years 2020 through 2022 been increased?

- Is the City planning to make annual deposits in the RHBT at higher levels?

- Are surplus revenues being used to retire long-term debt?

Adapt the Ten-Year Capital Strategy to a resource constrained environment

1. Slim down the bloated capital plan: The City releases a preliminary version of its long-term capital planning document, the Ten-Year Capital Strategy, with the January financial plan in every odd year. The two strategies released under Mayor de Blasio reached record sizes, $83.8 billion and $95.8 billion.7 The scope of the ten-year strategy has been unrealistic, including far more capital investment than the City could manage to undertake, and making it difficult to discern the capital priorities of City agencies. The City should focus on priority projects and reduce the funding level in the upcoming Ten-Year Capital Strategy.

2. Invest in critical infrastructure: Capital investment should be focused on projects that repair and improve the assets upon which businesses and residents rely—roads, bridges, the water and sewer system, and public facilities such as schools—and bring them to a state of good repair (SGR). New initiatives should only be included in the capital plan if they can be justified by a clear return on investment.

Key Questions

- What is the total Ten-Year Preliminary Capital Strategy?

- Are most of the City’s ten-year commitments for SGR? How much is devoted to expansion and purchase of new assets?

- How much additional debt will implementation of the capital strategy require?

Strengthen finances at public authorities

The financial health of three authorities—the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), NYC Health + Hospitals (H+H), and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA)—remains challenging. Despite considerable increases in City support, substantial needs persist.

1. Support implementation of NYCHA 2.0: City operating support for NYCHA has increased significantly; subsidies grew from $62.4 million in fiscal year 2014 to $178.9 million in fiscal year 2018, and nearly $100 million in annual payments from NYCHA to the City have been forgiven.8 While this has helped stabilize the authority’s operating budget, NYCHA nevertheless has $32 billion in capital needs over the next five years.9 The City unveiled NYCHA 2.0 in December, which provides a solid blueprint for NYCHA’s turnaround, and identifies possible sources for $24 billion in capital funding over 10 years. However, resources and actions on the part of federal, State, and City government, and the involvement of labor unions, are essential to the plan’s success. In addition, NYCHA should be incorporated fully into the City’s affordable housing plan, which would direct additional capital funds to the authority.

2. Rightsize the H+H subsidy: When announcing NYC Care, a plan to provide care coordination to uninsured New Yorkers at H+H, the City touted the authority’s financial turnaround, citing that it closed fiscal year 2018 with $747 million cash on hand ($137.7 million more than the prior year). H+H’s financial health ultimately depends on implementation of a substantial plan to close out-year budget gaps that reach $1.8 billion. Part of H+H’s progress has come from increased levels of City support, which are expected to reach $1.8 billion this year, a 30 percent increase over fiscal year 2014.10 The City should support H+H’s aggressive turnaround plan while ensuring it is implemented in a fiscally sustainable and responsible manner, with spending increases offset by efficiency savings and new revenues.

3. Support needed fare hikes and congestion pricing: The MTA’s fiscal outlook has worsened and substantial capital needs remain. The planned biennial fare increases and proposed congestion pricing plan are essential to provide recurring revenue to the MTA.

Key Questions

- What does the City plan to spend, in operating and capital dollars, to support NYCHA, H+H, and the MTA?

- Is the City increasing support of NYCHA and H+H by paying the cost of recent labor settlements?

Conclusion

The City has enjoyed the benefits of a sustained economic recovery that is approaching ten years, which allowed it to increase spending and headcount dramatically. Fiscal prudence calls on the City to prepare for a future economic downtown by containing spending growth, increasing reserves, focusing the capital plan, and stabilizing the public authorities.

Footnotes

- CBC adjusts spending figures to exclude Interfund Agreements, reserves, and for the surplus roll. CBC staff analysis of data from Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018 (October 31, 2018), and fiscal year 2014 edition, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/comprehensive-annual-financial-reports; City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, November 2018 Financial Plan: Full-Time and Full-Time Equivalent Staffing Levels (November 8, 2018), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/nov18-stafflevels.pdf, and email to Citizens Budget Commission staff (August 10, 2018).

- Fiscal year inflation projection is based on average across two calendar years. Office of Management and Budget forecast as reported by City of New York, Independent Budget Office, Still Rolling On: Slower Economic Growth Ahead, But Tax Revenue Will Continue to Rise (December 2018), https://ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/still-rolling-on-slower-economicg-growth-ahead-but-tax-revenue-will-continue-to-rise-december-2018.pdf.

- The remaining 3 percent are revenue actions. CBC staff analysis of data from City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, November 2018 Financial Plan: Citywide Savings Program (November 8, 2018), and financial plans from Fiscal Year 2016 Executive Budget to Fiscal Year April 2018 Executive Budget, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/omb/publications/budget-reports.page?report=Citywide%20Savings%20Prog.

- Michael Dardia and Rachel Bardin, “How Much to Bank on? When it Comes to Revenue Forecasting, Better Safe Than Sorry” Citizens Budget Commission Blog (April 12, 2015), https://cbcny.org/research/how-much-bank-when-it-comes-revenue-forecasting-better-safe-sorry.

- Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018 (October 31, 2018), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/CAFR2018.pdf.

- Includes General Obligation, Transitional Finance Authority other than Building Aid Revenue Bonds, Municipal Water Finance Authority, Sales Tax Asset Receivable Corporation, Tobacco Settlement Asset Securitization Corporation, and conduit debt. Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018 (October 31, 2018), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/CAFR2018.pdf, and Fiscal Year 2019 Annual Report on Capital Debt and Obligations (December 3, 2018), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Fiscal-Year-2019-Annual-Report-on-Capital-Debt-and-Obligations.pdf

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2018 Executive Ten-Year Capital Strategy (April 2017), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/typ4-17.pdf, and Fiscal Year 2016 Executive Ten-Year Capital Strategy (May 2015), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/typ5_15.pdf.

- Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018 (October 31, 2018), and fiscal year 2014 edition, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/comprehensive-annual-financial-reports/; and Sean Campion, Room to Breathe: Federal and City Actions Help NYCHA Close Operating Gaps, But More Progress Needed on Implementing NextGenNYCHA (Citizens Budget Commission, July 19, 2017), https://cbcny.org/research/room-breathe.

- The City, federal prosecutors, and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development announced on January 31, 2019 that a federal monitor will be appointed to oversee NYCHA and the City will be expected to contribute $2.2 billion over 10 years to NYCHA's capital plan. See: U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Attorney’s Office, Southern District of New York, Manhattan U.S. Attorney Announces Settlement with NYCHA and NYC to Fundamentally Reform NYCHA Through the Appointment of a Federal Monitor and the Payment by NYC Of $1.2 Billion of Additional Capital Money Over the Next Five Years (press release, June 11, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/manhattan-us-attorney-announces-settlement-nycha-and-nyc-fundamentally-reform-nycha; United States District Court, Southern District of New York, Opinion and Order, 18cv5213 (November 14, 2018), http://www.nysd.uscourts.gov/cases/show.php?db=special&id=670; and Jillian Jorgensen and others, "Federal government to impose monitor and shake up top brass at NYCHA, sources say," NY Daily News (January 31, 2019), https://www.nydailynews.com/news/politics/ny-pol-nycha-hud-deblasio-carson-federal-monitor-20190131-story.html.

- Net City subsidy reflects City payments to H+H, supplemental Medicaid Funds, and forgiving certain H+H payments to the City for costs such as medical malpractice, employee fringe costs, and debt service. Does not reflect City payments to H+H for direct services, such as correction health. New York City Independent Budget Office, City Subsidies Grow, Federal Cuts Delayed but Fiscal Challenges Remain for NYC’s Public Hospitals (March 2018),https://ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/city-subsidies%20-grow-federal-cuts-delayed-but-fiscal-challenges-remain-for-nycs-public-hospitals-march-2018.pdf; and City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2019 Adopted Budget: Supporting Schedule (June 18, 2018),https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/ss6-18.pdf.