Tax Increment Financing: A Primer

Tax increment financing (TIF) originated in the 1950s as an urban renewal strategy and has developed into one of the country’s most commonly used economic development tools. Today nearly every state authorizes some form of TIF, which is used to fund hundreds of projects each year.

When it opened in 2015, the 34th Street-Hudson Yards subway station attracted the interest of New Yorkers eager to see the first addition to New York’s subway system in more than 25 years. The opening also marked a different milestone: the first time New York City had used a form of TIF to pay for a major capital project. New York policymakers and advocates have since floated TIF as a tool to pay for a variety of proposed infrastructure projects, including the construction of the BQX streetcar line, the redevelopment of Penn Station, and the extension of the Seventh Avenue Line (Number 1) subway to Red Hook, Brooklyn.

Proponents present TIF as a flexible, self-financing tool to pay for infrastructure projects without raising taxes or diverting resources from other capital needs. But TIF is not without risks.

By definition TIF diverts property tax revenue from a local government’s general operating budget; when used improperly it can shift economic activity and tax revenue from one location to another without creating net new growth, circumvent debt limits, or shift operating spending off-budget. TIF projects can also increase the demand for city services, but such financing limits the ability of local governments and schools to fund those services with property tax revenue. Additionally, cost overruns or revenue shortfalls can jeopardize a TIF project’s financial feasibility and necessitate additional public subsidies.

This report provides an overview of TIF and a five-point checklist drawn from lessons learned from past projects to help identify potential TIF projects.

How TIF Works

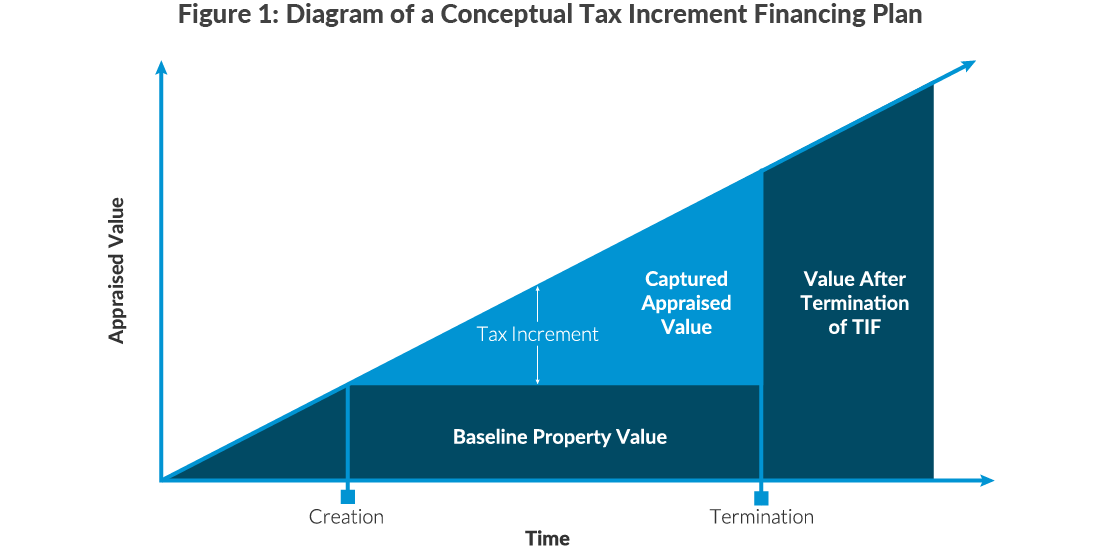

The concept behind TIF is that public investments in infrastructure and services will induce private development, which in turn will lead to higher property values, more employment, and additional tax revenue. Since this economic activity and revenue growth would not occur “but for” upfront investments made by the public sector, cities can capture the new property tax revenue to pay for the investments that sparked the growth. For localities authorized to assess other types of taxes, additional sales and income tax revenues generated by the new economic activity may offset some of the property tax revenue diverted to the TIF district.

TIF has developed into one of the country’s most commonly used economic development tools. As of 2015, 49 states and the District of Columbia allowed cities to use some form of TIF, and it has been used in recent years to finance many of the country’s largest development projects. New York City used a variation on TIF to fund the extension of the Flushing Line (Number 7) subway to the Hudson Yards district without state or federal assistance. The Chicago City Council approved a TIF district to fund the local share of a proposed subway extension.1 San Francisco and Denver created TIF districts to finance new central city transit stations that will anchor redevelopment districts.2 Other cities, including Atlanta and Baltimore, have used TIF to build new parks and infrastructure to induce development.3

Every state that allows for TIF has its own set of rules to govern how local governments can use TIF districts.4 These enabling laws vary, but the best-designed TIF programs follow the same general pattern from conception to termination:

1) A municipality identifies an area in need of redevelopment, or a developer approaches the city with a redevelopment plan that would not be viable without specific public improvements.

2) The municipality conducts what is commonly known as the “but for” analysis that addresses two questions: is the proposed TIF district ”blighted” or in need of redevelopment, and would the proposed development occur “but for” the TIF-funded capital improvements? If evidence of blight is found and the project satisfies the “but for” analysis, it can move past the initial planning stages.

3) The municipality begins work on a district improvement plan. The properties that will benefit from the investment are identified, and the total assessed value of properties within the potential TIF district is determined. This establishes the baseline value from which the incremental tax revenue is calculated. In most TIF districts, the baseline is frozen at this “year zero” amount; in others, it grows at a specified rate of inflation established by law or by negotiation with affected tax districts.5 This analysis allows the city to project the property tax revenue that the project will generate over time in order to develop a borrowing plan or a plan to reimburse a developer’s upfront infrastructure expenditures. The city then can begin to negotiate covenants with bond underwriters and agreements with real estate developers and relevant public agencies. A local development corporation (LDC) could also be created to oversee the capital improvement and financing plan.

4) After securing the necessary planning approvals, the local government (or the LDC) launches the TIF district. If necessary, bonds are issued and the proceeds used to fund the upfront infrastructure project costs and other expenditures. In other cases, a developer will pay for the improvements and get reimbursed in whole or in part by the proceeds from a TIF bond, or directly from incremental TIF revenue as it is collected.

5) The new investments begin to induce development, and total property values within the TIF district begins to rise. This growth in property value translates into an increase in the properties’ assessed value, which generates incremental property tax revenue above the baseline value, which then flows into a special TIF fund. If bonds were issued TIF revenue will be used to repay the bonds; otherwise, the incremental revenue will be used to fund expenditures on a pay-as-you-go basis or to reimburse developers for their upfront investments. The incremental tax revenue continues to flow into the TIF fund until the district expires. The maximum TIF district length varies by state, and many states allow for extensions of the initial length. The most common TIF district length is between 20 and 29 years, though some jurisdictions allow up to 50 years.6

6) After the district expires, properties within the TIF district fully return to the tax rolls and resume paying taxes to all of the applicable tax jurisdictions based on the full assessed value.

TIF Checklist: Factors to consider

In a political environment marked by diminished federal aid, stagnating state and local tax receipts, and restrictions on municipal spending and taxation, TIF is appealing because it allows local leaders to pursue economic development projects without the need to raise more local tax revenue or to rely on increased assistance from state or federal governments. In the rush to approve these projects, however, potential risks can be overlooked. The Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) reviewed studies of TIF projects across the country, including successful projects such as New York’s Hudson Yards and more problematic districts in cities such as Chicago.

Based on this research, CBC identified five questions that governments should ask before launching a redevelopment project to identify those in which TIF would be appropriate.

1. Does the project pass the “but for” test?

Most states require municipalities to answer a simple question before creating a TIF district: would the development and property value appreciation occur in the absence of the TIF-funded capital project? Projects that satisfy the “but for” test typically involve large capital expenditures that are too expensive, logistically complex, or otherwise unprofitable for the private sector to execute, such as brownfield remediation, land assembly, and the extension of basic infrastructure like roads, transit, or utilities needed to make further development possible.7

For example, before approving the Hudson Yards project, New York City officials conducted a planning study that found the project area’s land uses and buildings were underutilized relative to the rest of midtown Manhattan, and that the district could not be transformed into a high-density commercial district without the combination of a zoning change, the extension of the number 7 subway line, the construction of public open space, and an incentive program to attract development. Based on the study’s projections, these public investments and actions would create enough tax revenue to finance the project’s $3 billion cost.8

Another example, Atlantic Station, a TIF project in Atlanta, needed to build public utilities and remediate a contaminated 138-acre industrial property to allow for the creation of a new, mixed-use district.9

A common way that TIF projects can fall short on the “but for” test is when TIF revenue is used to subsidize private development or companies that do not need incentives to invest in specific areas. Chicago, for example, has been criticized for using TIF revenue to fund relocation subsidies that enticed major corporations to move to existing downtown office buildings without an analysis of whether those firms needed relocation incentives.10 Other cities have been criticized for using TIF to attract new development that likely would have occurred without incentives. A study of TIF districts in the St. Louis metropolitan area found that they are more likely to be used in higher-income suburban areas with strong commercial real estate markets than in disadvantaged neighborhoods. In St. Louis, the lack of a strong “but for” provision, combined with a highly fragmented political structure, led local governments to use TIF as a tool to attract development in order to boost their tax bases, even though many of those projects did not require the use of incentives.11

2. Will the investment generate new economic activity or simply shift it from elsewhere?

Cities often use TIF to incentivize businesses to move from one area of a city or region to another without resulting in an overall increase in economic activity. This most often occurs for retail and entertainment projects, for which there is a finite level of consumer demand within a region. While there is mixed evidence of the impact of office and industrial TIFs on employment, studies have shown that retail TIFs tend to shift consumer spending and retail jobs within municipalities without producing a net gain in economic activity.12

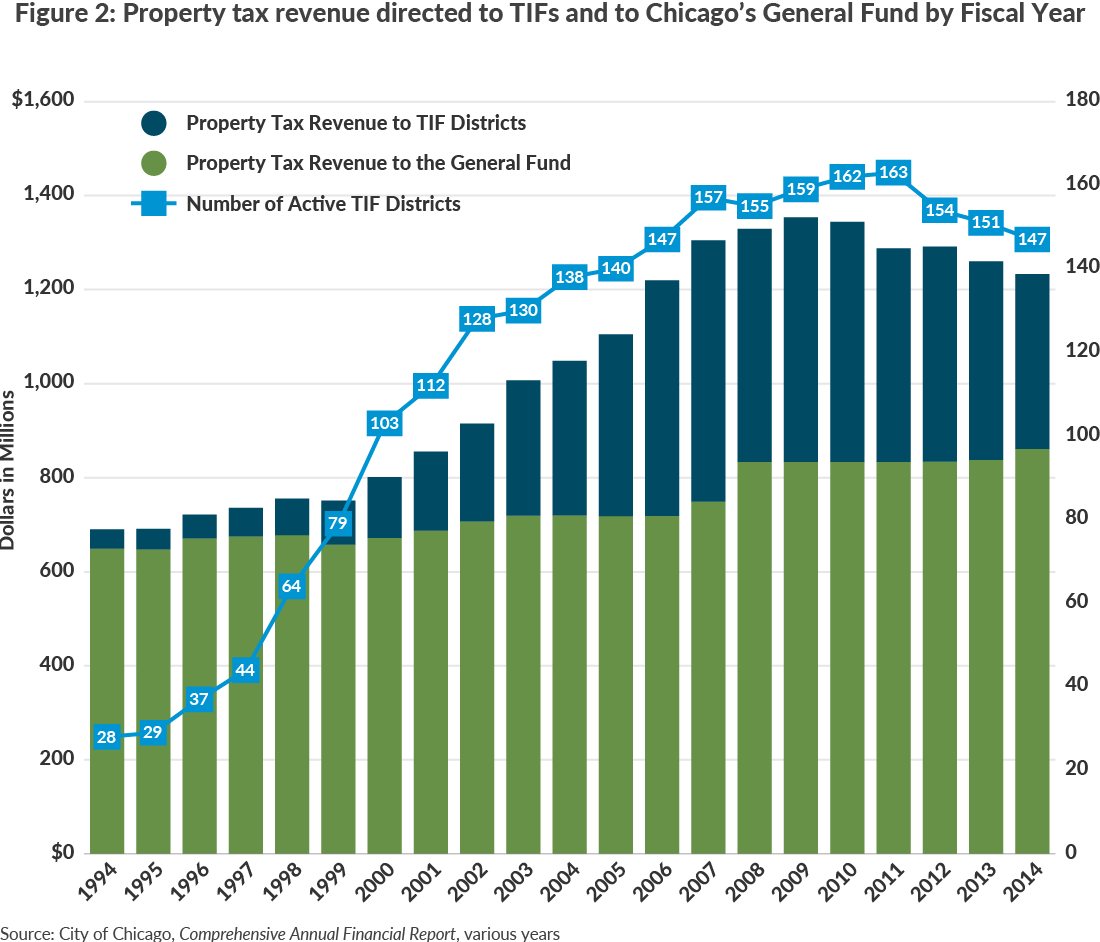

In cities like Chicago, where TIF districts cover a significant share of the city’s commercially zoned land, it has been found that the use of TIF has not stimulated job growth, business formation, or building permit activity after accounting for broader economic trends.13 Rather, Chicago frequently used TIF to shift economic activity within the city limits. This is similar to the experience in the St. Louis region, where local governments have used TIF to incent businesses to move to affluent neighborhoods from nearby jurisdictions in order to capture sales and property tax revenue rather than as a tool to reinvest in low-income neighborhoods.

Critics of Hudson Yards contend that most of the companies that have announced their intentions to move there will be relocating from elsewhere in the city, raising office vacancy rates in Midtown.14 The project’s supporters, however, argue that some of these companies would have left New York City or reduced their New York-based workforce if the City did not encourage the development of modern office space in Hudson Yards, and therefore, the project is vital to New York’s competitiveness as a global city.15

Another questionable use of TIF is where a district is too small and will not generate enough revenue to pay for projects that will increase property values. In Chicago a study found that over a 13-year period a majority of the city’s TIF districts raised and spent less than $10 million each. These small districts were often established to fund streetscape projects or to subsidize big-box retailers and failed to generate much property appreciation or new tax revenue in surrounding neighborhoods.16

3. Is the project’s expected return on investment strong enough to justify diverting revenue from other uses?

When a city creates a TIF district, its leaders make a decision to pledge future revenue to a current project instead of allowing it to be used to pay for other prospective needs.

Supporters contend TIF does not need to be evaluated in comparison to other capital needs because the investment will pay for itself out of new revenue.17 However it is not always clear whether a proposed TIF will generate enough additional benefits in the form of jobs, services, or sales and income taxes to justify the diversion.

Like most states, New York does not require TIF districts to return surplus revenue to the tax jurisdictions in which they are located. This means that the TIF district retains all of the incremental property tax revenue generated within its boundaries, and taxpayers from outside the TIF district contribute to the cost of providing city services within the TIF boundaries. Further, when districts are allowed to retain surplus revenue, the funds can be used as an off-budget source to pay for activities unrelated to the TIF’s original mission. Even if a TIF district’s development agreement includes a provision for sharing surplus revenue with the city, as is the case for Hudson Yards, taxpayers still could wind up subsidizing the cost of providing services to this area if the surplus does not materialize.

It is possible that a TIF funded project could create enough jobs or other benefits to make this expense worthwhile; the project’s total return on public investment should include an assessment of the net value after also taking into account the cost of providing public services in the TIF district. The Hudson Yards project, for example, generates net new income and sales tax revenue for the City and State and ground lease revenue for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) in addition to the development-related revenue sources pledged to the repayment of the Hudson Yards bonds. These revenue sources are offset by additional costs to provide city services like police, fire, and sanitation to the district’s workers and residents, as well as the cost of operating the extended 7 subway line.

In Chicago the value of property taxes diverted to TIF districts accounted for nearly all of the city’s property tax revenue growth during the 1990s and 2000s. Neighborhoods that fell outside of a TIF district, or in a less lucrative TIF zone, had to compete for a limited pool of revenue, while more affluent areas of the city were able to retain locally generated revenue for their own use. Additionally, because a portion of Chicago’s TIF revenue was diverted from other taxing jurisdictions, including Chicago Public Schools, high-income neighborhoods with high-revenue TIF districts were able to grow their tax base at the expense of the rest of the city and other public entities.18

Similarly, a study of California’s redevelopment districts found that few of the state’s TIF districts created enough economic growth to justify the diversion of taxes from other public needs. The incentive to capture revenue led many cities to designate areas as TIF districts even though they were not in need of redevelopment.19

4. Will the district generate sufficient revenue to repay debt service and other costs? If not, how will the shortfall be covered?

By design, TIF projects experience a lag between upfront capital investments and the collection of incremental property tax revenue. It takes time for new real estate projects to come online, and market conditions can shift. As part of the TIF process, cities should test their revenue projections against a range of economic scenarios, including the impact of possible cost overruns, revenue shortfalls, cost spillovers, and economic downturns.

To mitigate these risks, New York City agreed to guarantee the interest payments on up to $3 billion in bonds for the Hudson Yards project. Under the bond covenant, the City will make up the shortfall between revenue generated within the Hudson Yards district and the interest due on bonds in a given year. The City ultimately paid $359 million from its general fund to subsidize Hudson Yards’ interest payments after the Great Recession delayed the pace of office development. It also funded an additional $266 million in capital cost overruns and canceled one of two planned subway stations after the project went over budget.20 For Atlanta’s Atlantic Station, the project’s master developer agreed to fund the shortfall between tax revenue and debt service payments. This agreement also had the benefit of placing the risk of cost overruns onto the private sector, which greatly benefited the city after the budget increased from $120 million to $170 million due to changes in market conditions following the 2001 recession and higher-than-expected remediation costs.21

New York and Atlanta were both able to withstand delays and cost overruns because the upfront investments created enough value for developers to see the projects through to completion. These public investments sparked significant new commercial development, but it was only through careful public planning that the projects were able to surmount the risks inherent in development projects.

Cities in less affluent or desirable markets have a smaller margin for error. The Troy Downtown Development Authority in Michigan defaulted on $14 million in TIF debt issued to fund the construction of a community center and road improvements. During the Great Recession the assessed values of this TIF district’s largest commercial properties fell below their pre-TIF baseline levels, which left insufficient revenue to fund debt service payments.22 The City of Troy eventually bailed out the project by issuing new general obligation bonds to assume the interest and principal obligations from the defaulted TIF bonds.

5. Are general obligation bonds a better option?

TIF bonds are backed by as-yet-unrealized future property tax revenue streams, while general obligation bonds are backed by a municipality’s full faith and credit. This makes TIF bonds riskier and more costly than traditional municipal bonds. Without a pledge by a municipality to guarantee the TIF bonds, investors will demand higher interest rates to compensate for the additional risk. In the case of Hudson Yards, the City's decision to guarantee interest payments allowed the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation, a local development corporation created by the City, to borrow at rates comparable to what the City pays on its general obligation debt.

The complexity of TIF deals also leads to higher transaction costs; the fees for consultants, bond lawyers, accountants, financial advisors, and underwriters increase as a project grows more complex.

In some cases the benefits of using TIF outweigh the additional costs. The ability to self-finance the Hudson Yards project allowed New York City to bypass the traditional federal and MTA funding processes, which significantly accelerated the project’s construction timeline and funded the project at a time when the MTA was focusing its resources on East Side Access and the Second Avenue Subway.

Other projects could use TIF to finance the public half of a public-private partnership, with the goal of reducing the overall construction costs and transferring risk onto the private partner.

Conclusion

TIF can be a creative way to stretch a municipality’s capital dollars, but it is not a panacea for all infrastructure investments or economic development projects. The history of TIF shows that successful projects are the product of substantial due diligence, but that even well-designed plans can come at a cost to taxpayers. The five questions presented in this report should help inform the decision as to whether a TIF makes sense for a specific project. Answering these questions, coupled with strong transparency provisions, can help protect future taxpayers against the risks associated with TIF projects.

Appendix: The History of TIF Districts in New York State

New York State’s tax increment financing law, originally passed in 1984, authorizes municipalities to pledge their future property tax revenue to finance a broad list of redevelopment projects, including land acquisition, demolition, site preparation, and the construction of public infrastructure and open space. New York’s TIF law requires municipalities to demonstrate the existence of blight and that redevelopment would not be feasible “but for” the use of TIF.

To encourage its use, the Legislature also exempted TIF bonds from the formulas used to determine municipal debt limits.23 The law was amended in 2012 to make it easier for cities outside of New York City to dedicate school tax revenue to TIF projects, and again in 2016, to allow cities to create TIF districts to fund MTA projects.

Unlike most of the country, which has eagerly embraced TIF, New York’s cities have been reluctant to embrace the financing tool. Since its approval in 1984 only two municipalities, the Village of Elmsford, and the Town of Victor, created TIF districts through the enabling law.

An alternative version of TIF known as Pilot Increment Financing (PIF) has proven more popular among New York municipalities. PIF allows local governments to create TIF-like districts without the constraints of the TIF enabling law. PIF agreements are similar to TIF districts, but involve the use of payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) instead of the property tax levy. Local governments enter into PILOT agreements with the owners of specific redevelopment sites and agree to use a portion of the proceeds to fund capital improvements related to the development.24 Outstanding PIF debt in New York totaled $75.4 million in June 2017.25

New York City used a variant of PILOT increment financing to pay for the extension of the number 7 subway line to Hudson Yards. The transaction was not structured through the State’s TIF enabling law, in part because the City determined that it was necessary to offer tax abatements, which required the use of PILOT agreements, to attract new office development.

This policy brief is based on research completed by CBC Public Policy Fellow Flavia Leite. It was prepared by Sean Campion, Senior Research Associate. Carol Kellermann, President; Maria Doulis, Vice President; Timothy Sullivan, Director of Research; and Ana Champeny, Director of City Studies, provided editorial guidance. The report was edited by Laura Colacurcio and formatted for publication by Kevin Medina.

A draft of this policy brief was sent to New York City Economic Development Corporation and Office of Management and Budget officials, as well as other interested parties. We are grateful for their comments and suggestions.

Download Report

Tax Increment Financing: A PrimerFootnotes

- Fran Spielman, “City Council unanimously approves transit TIF,” Chicago Sun Times (November 30, 2016) http://chicago.suntimes.com/chicago-politics/city-council-unanimously-approves-transit-tif/; and Daniel Hertz, “The values of value capture,” City Observatory (December 7, 2016), http://cityobservatory.org/the-values-of-value-capture/.

- Matthew Dickens, Value Capture for Public Transportation Projects: Examples (American Public Transportation Association, August 2015), www.apta.com/resources/reportsandpublications/Documents/APTA-Value-Capture-2015.pdf.

- Atlanta BeltLine, “How the Atlanta BeltLine is Funded” (accessed December 4, 2017), https://beltline.org/about/the-atlanta-beltline-project/funding/; and Luke Broadwater “City Council approves $660 million bond deal for Port Covington project,” Baltimore Sun (September 19, 2016), www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/baltimore-city/politics/bs-md-ci-port-covington-council-20160919-story.html.

- Council of Development Finance Agencies, “TIF State-By-State Map” (accessed December 4, 2017), www.cdfa.net/cdfa/tifmap.nsf/index.html.

- The majority of TIF districts capture incremental property tax revenue, but some states grant cities the ability to capture incremental sales taxes, personal or income business taxes, or payments in lieu of taxes, and pledge them to back bonds. See: Council of Development Finance Agencies, Tax Increment Finance State-by-State Report: An Analysis of Trends in State TIF Statutes (2015), www.cdfa.net/cdfa/cdfaweb.nsf/ordredirect.html?open&id=201601-TIF-State-By-State.html.

- Council of Development Finance Agencies, Tax Increment Finance State-by-State Report: An Analysis of Trends in State TIF Statutes (2015), www.cdfa.net/cdfa/cdfaweb.nsf/ordredirect.html?open&id=201601-TIF-State-By-State.html.

- Rachel Weber and Laura Godderis, “Tax Increment Financing: Process and Planning Issues,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper (2007), datatoolkits.lincolninst.edu/subcenters/teaching-fiscal-dimensions-of-planning/materials/goddeeris-weber-financing.pdf.

- Cushman & Wakefield, Inc., “Hudson Yards Demand and Development Study,” (November 2006), nycbonds.org/HYIC/html/hyic_disclaimer.html.

- Rachel Weber and Laura Godderis, “Tax Increment Financing: Process and Planning Issues,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper (2007), datatoolkits.lincolninst.edu/subcenters/teaching-fiscal-dimensions-of-planning/materials/goddeeris-weber-financing.pdf.

- Ellyn Fortino and Margaret Smith, “Corporate Giants Received TIF Money, Records Show,” New York Times (February 26, 2011), www.nytimes.com/2011/02/27/us/27cnctif.html.

- Thomas Luce, “Reclaiming the Intent: Tax Increment Finance in the Kansas City and St. Louis Metropolitan Areas” (prepared for the Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy, April 2003), www.cdfa.net/cdfa/cdfaweb.nsf/ord/0c6101d0958806d1882579360063db3f/$file/lucetif%5B1%5D.pdf.

- Paul F. Byrne, “Does Tax Increment Financing Deliver on its Promise of Jobs? The Impact of Tax Increment Financing on Municipal Employment Growth,” Economic Development Quarterly (December 3, 2009), journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0891242409350887.

- T. William Lester, “Does Chicago’s Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Program Pass the ‘But-For’ Test? Job Creation and Economic Development Impacts Using Time-series Data,” Urban Studies (July 10, 2013), journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0042098013492228?journalCode=usja.

- At least 5 million square feet of office vacancies elsewhere in the city are due to tenants that relocated to Hudson Yards. See: Holly Dutton, “Midtown Loses 5.1M s/f in office deals to Hudson Yards,” Real Estate Weekly (August 16, 2017), http://rew-online.com/2017/08/16/colliers-midtown-relocation-hudson-yards/.

- Related Companies, “New Report Details Substantial Economic Impact of Hudson Yards Development” (press release, May 2, 2016), www.hudsonyardsnewyork.com/press-releases/new-report-details-substantial-economic-impact-of-hudson-yards-development/.

- City of Chicago, TIF Reform Panel, Findings and Recommendations for Reforming the Use of Tax Increment Financing in Chicago: Creating Greater Efficiency, Transparency and Accountability (August 23, 2011), www.cityofchicago.org/content/dam/city/depts/mayor/Press%20Room/Press%20Releases/2011/August/8.29.11TIFReport.pdf.

- Rohit Aggarwala, “Brooklyn-Queens streetcar could transform waterfront without gentrifying it,” Crain’s New York Business (August 6, 2017), www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20170806/OPINION/170809947/brooklyn-queens-streetcar-could-transform-waterfront-without-gentrifying-it-but-the-bqxs-funding-is-misunderstood.

- Robert Bruno and Alison Dickson Quesada, Tax Increment Financing and Chicago Public Schools: A New Approach to Comprehending a Complex Relationship (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Labor Education Program, December 2011), https://ler.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Bruno_Quesada_12152011.pdf.

- Michael Dardia, Subsidizing Redevelopment in California (Public Policy Institute of California, January 1998), www.ppic.org/content/pubs/report/R_298MDR.pdf.

- New York City Independent Budget Office, As Hudson Yards Refinances Old Debt: Need for Nearly $100 Million in Additional Funding Emerges as Costs Continue to Exceed Plan (June 2017), http://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/as-hudson-yards-refinances-old-debt-need-for-nearly-100-million-in-additional-funding-emerges-as-costs-continue-to-exceed-plan.pdf.

- Rachel Weber and Laura Godderis, “Tax Increment Financing: Process and Planning Issues,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper (2007), datatoolkits.lincolninst.edu/subcenters/teaching-fiscal-dimensions-of-planning/materials/goddeeris-weber-financing.pdf.

- Chad Halcolm, “Troy’s DDA may default on $14 million in bond debt,” Crain’s Detroit Business (September, 7 2012), www.crainsdetroit.com/article/20120907/FREE/120909934/troys-dda-may-default-on-14-million-in-bond-debt.

- General Municipal Law, Sec. 970-o (1984).

- Diane Church, “The use of PILOT increment financing (PIF) to offset project costs,” New York Real Estate Journal (January 27, 2009), http://nyrej.com/the-use-of-pilot-increment-financing-pif-to-offset-project-costs.

- New York State Authorities Budget Office, Annual Report on Public Authorities in New York State (July 1, 2017), www.abo.ny.gov/reports/annualreports/ABO2017AnnualReport.pdf.