Why Spend to Save?

Early Retirement Incentives Save Less than Attrition

As Mayor Bill de Blasio continues to seek $1 billion in recurring savings from municipal labor unions, yesterday his Administration indicated support for a targeted early retirement incentive (ERI) that would provide additional pension benefits to certain New York City employees in exchange for their departing city service.1 While an ERI can induce employees to leave city employment quickly, it is a more costly workforce reduction strategy than attrition or layoffs. In light of the City’s fiscal stress and the availability of other options to balance the budget, the City should reduce its workforce through attrition and not pursue the ERI.

Last year, the State Legislature introduced an ERI bill (A.11089/S.9041) for certain City employees. Using this proposal as an illustration, the Citizens Budget Commission estimates it would cost the City approximately $110,000 per participant over five years, which would offset 19 percent of the City’s savings from not having to pay the separated employee’s salary and benefits.2 Furthermore, nearly one-third of the ERI incentive payments would likely go to employees already planning to retire—an unneeded expense.

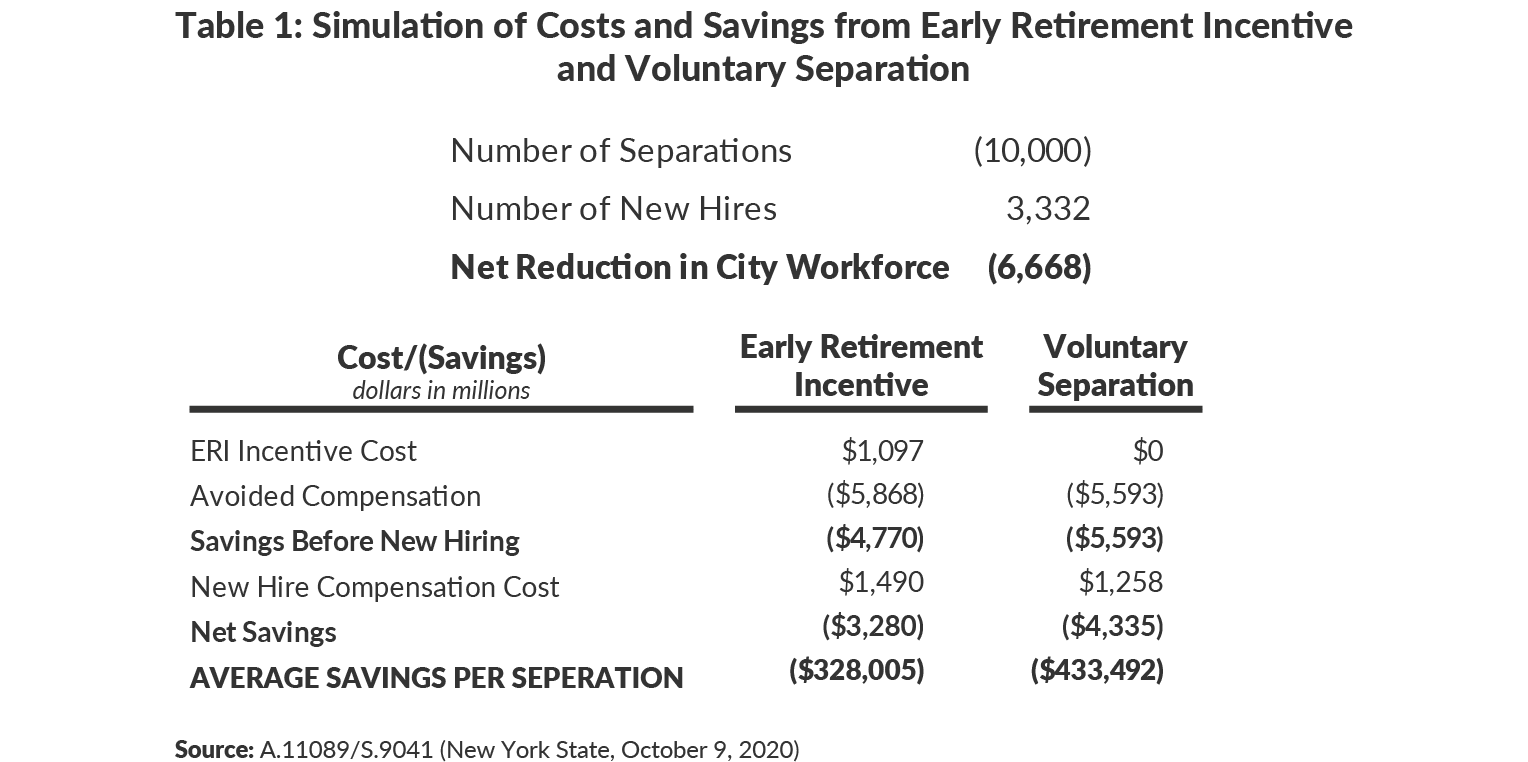

Finally, ERI savings will be significantly diminished if the City chooses to replace some of the positions. For example, if 10,000 employees take the ERI and the City follows its current practice for its partial hiring freeze―hiring 1 new employee for every 3 vacancies―the ERI could cost $1.1 billion and the City’s net savings could be $3.3 billion over 5 years. In contrast, if the 10,000 employees voluntarily left city employment and one-third of the vacancies filled, the net savings over five years could be 32 percent higher, or $4.3 billion.

Analysis

A.11089/S.9041 would permit the City to offer an ERI to employees in three New York City pension funds—the New York City Employee Retirement System (NYCERS), the New York City Teachers Retirement System (TRS), and the New York City Board of Education Retirement System (BERS).3 Eligible titles would be decided based on potential for layoff, while ensuring that reductions do not result in unacceptable reduction in the provisions of services, health and safety, or the City’s ability to raise revenue. The City’s decisions about eligibility would affect the potential savings.

The incentive has two parts:

- Part A: Provides an additional service credit to eligible members equal to one-twelfth of a year for each year of pensionable service, for a maximum of 36 months. To be eligible employees must be:

- Eligible for a service retirement,

- 50 years of age with 10 years of service, and not in a plan that permits retirement at half-pay at with 25 years of service without regard to age, or

- In a plan that permits retirement at half-pay with 25 years of service without regard to age, if the employee would reach 25 years with the additional credits.

- Part B: Eliminates the early retirement reduction factor for qualifying members at least 55 years of age with 25 years of service.

The New York City Actuary, which prepared a fiscal estimate for the bill, estimates that 75,610 employees are eligible, and that the City would need to make an additional average pension contribution of $92,400 per retiree under Part A and $128,800 per retiree under Part B over five years, with no payment due in the first year. These estimates are used to compare savings for 10,000 employees leaving City service with and without an ERI, based on assumptions delineated below.4 There are three key findings:

1. Gross ERI savings would be 14 percent less than through attrition. Over five years, the ERI would save $4.8 billion compared to $5.6 billion otherwise. While the ERI’s gross savings would be $5.9 billion, that savings would be reduced by the ERI-increased pension costs of $1.1 billion. (See Table 1.)

2. Approximately $350 million of the ERI costs are likely to be an unneeded expense. CBC evaluation of a prior State ERI offered in the wake of the “Great Recession” found about 32 percent of retirements would have happened without the ERI.5 Applying this ratio to estimated retirements indicates this ERI will provide $351 million in benefits to those who are likely to retire without them.

3. Savings would be further reduced by refilling some of the vacant positions. If the City maintains the current hiring freeze in which 1 of every 3 vacant positions is filled, the compensation cost for the new employees would be $1.5 billion, reducing the net savings to $3.3 billion, or about $328,000 per retiree over five years. In contrast, the same pattern of new hiring to fill positions vacated through normal attrition (a mix of retirements and other separations) would produce $1.3 billion in new compensation costs, and net savings of $4.3 billion, or about $433,492 per separation over five years. In other words, per-person savings through attrition would be 32 percent greater than savings through an ERI.

Assumptions

- There are 10,000 retirees under ERI, evenly split between Part A and Part B. Retirees are distributed across the three pension plans in proportion to the eligible population.

- There are 10,000 voluntary separations; 3,200 or 32 percent retire, while the rest resign or are terminated.

- One-sixth of the separations are assumed to be filled in year one and one-sixth are assumed filled in year two.

- The cost of the ERI, based on the Actuary’s fiscal note, is $109,746 per retiree. The additional cost is amortized over four years, in years two to five.

- The retiree’s average salary, based on the Actuary’s fiscal note, is $90,200. New employees replacing retirees are hired at 70 percent of this salary in year one, and 72 percent in year two.

- The average salary for a voluntary separation is assumed to be $70,000. New employees replacing voluntary separations are hired at 70 percent of this salary in year one, and 72 percent in year two.

- All salaries increase 2 percent annually.

- Fringe savings for retirees are 25 percent of salary; retirees continue to be eligible for health insurance. Fringe savings for other separations are 50 percent of salary. Fringe costs for new hires are 50 percent of compensation.

- The analysis did not consider other costs the City may incur upon an employee’s retirement or resignation, such as accrued vacation payments.

Footnotes

- Testimony of Steve Banks, City of New York, Office of Labor Relations, First Deputy Commissioner and General Counsel, before the New York City Council Committee on Civil Service and Labor (January 27, 2021).

- The average cost assumes that half of the elections are under Part A, which has a four-year cost of $92,400, and half are under Part B, which has a four-year cost of $128,800. Retirees may continue to receive health insurance and welfare fund benefits from the City, but other fringe benefits would end. See: A.11089/S.9041 (New York State, October 9, 2020), https://assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?default_fld=%0D%0A&leg_video=&bn=A11089&term=2019&Summary=Y&Text=Y.

- A.11089/S.9041 (New York State, October 9, 2020), https://assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?default_fld=%0D%0A&leg_video=&bn=A11089&term=2019&Summary=Y&Text=Y.

- CBC did not estimate the potential saving associated with layoffs because headcount reduction through attrition minimizes the negative impact on employees, and the de Blasio Administration has agreed to no layoffs with several of the City’s unions already.

- Tammy Gamerman, “How Much Did New York’s 2010 Early Retirement Incentive Save?” Citizens Budget Commission Blog (October 25, 2011), https://cbcny.org/research/how-much-did-new-yorks-2010-early-retirement-incentive-save.