How Much Did New York’s 2010 Early Retirement Incentive Save?

In June 2010 the New York State budget was two months past due; Governor David Paterson’s calls for state employee furloughs and salary freezes had been rebuffed by labor union leaders; and a no-layoff pledge for state workers, agreed to in exchange for pension reforms for new hires, was in effect through the end of the calendar year. The Governor sought $250 million in labor savings but had few options to meet this target.

Thus, on June 2, 2010, Governor Paterson authorized the Early Retirement Incentive (ERI) program for state employees; employees of local governments opting to participate also were eligible.[1] Early retirement programs are favored by labor unions because they avoid the adverse personal impacts of layoffs or other compensation givebacks and because they are voluntary and add to the income of those choosing to participate. Employers agree to these programs expecting that taking high-paid workers off the payroll will yield substantial savings in the short run and that those savings will be only partly offset by the additional future pension fund contributions required to finance the incentives. Although New York has offered such programs in the past, little is known about their actual cost effectiveness.

Based on recently available data, the CBC estimates that over two years the ERI saved New York State $249 million and New York’s local governments $402 million. The combined $681 million savings is the net of gross savings from two-year payroll reductions of $1.4 billion minus pension benefit costs of $755 million. The savings are diminished to the extent early retirees are replaced by new hires. Moreover, the savings come at the cost of losing 9,311 experienced workers, potentially lowering the level of services.

While substantial, the ERI net savings are less than would have been saved if the Governor had been able to achieve the same headcount reduction through layoffs. Those layoffs would have saved New York State and its local governments an additional $136 million, or a total of $817 million, in the same time period.

Background: The 2010 Early Retirement Incentive

To qualify for pension benefits, most New York State and local government employees, excluding police and fire department employees, must have at least five years of service and be at least age 55. The amount of benefits is a function of average pay during the highest-paid three consecutive years of work and the number of years of service. Workers with less than 30 years of service who retire between ages 55 and 62 incur a reduction in benefits.[2]

The ERI offered workers a lower minimum retirement age and/or higher benefits under two options. The first option, known as Part A, gave workers an additional month of credit toward benefits for each year worked up to 36 months. It also allowed employees with 10 years of service to retire as early as age 50 with standard benefit reductions. With certain exemptions, employees were eligible for Part A if their employer either targeted the position for permanent elimination or committed to a 50 percent salary reduction for any replacements over two years. Under the second option, Part B, workers age 55 and above with 25 years of service could retire without penalty. Employers could deny Part B requests from employees in critical public safety or health positions. Members of the Police and Fire Retirement System were excluded from the ERI entirely. Local government employers had the option to participate or not. The City of New York did not participate, except for the City University of New York. Workers had to decide whether to opt for the ERI within a few months of its authorization.

The enhanced pension benefits were significant. The Empire Center calculated that the annual pension for a 62 year-old worker with 25 years of service and a final average salary of $60,000 would increase 8.3 percent, from $30,000 to $32,496.[3] A similar worker with 31 years of service would see his or her pension rise 6.3 percent, from $36,900 to $39,222.

The ERI legislation stipulated that the State and other participating government employers had to pay for the “pension benefit costs” resulting from the incentive. These payments equal the actuarial present value of the new retirement benefits over the retirees’ lifetimes. The state and other participating employers have five years beginning in state fiscal year 2012 to pay the appropriate retirement fund. Those who use the full five years will be charged interest. The authorizing legislation did not disclose the interest rate, but the State Comptroller recently set the rate at 7.5 percent, the pension funds’ assumed rate of return. State legislation authorized Westchester County to finance the payment on its own rather than pay the 7.5 percent interest rate. The County, which enjoys top credit ratings, believes borrowing will lower its interest costs by $3.5 million.[4]

At Least $755 Million in Added Retirement Costs

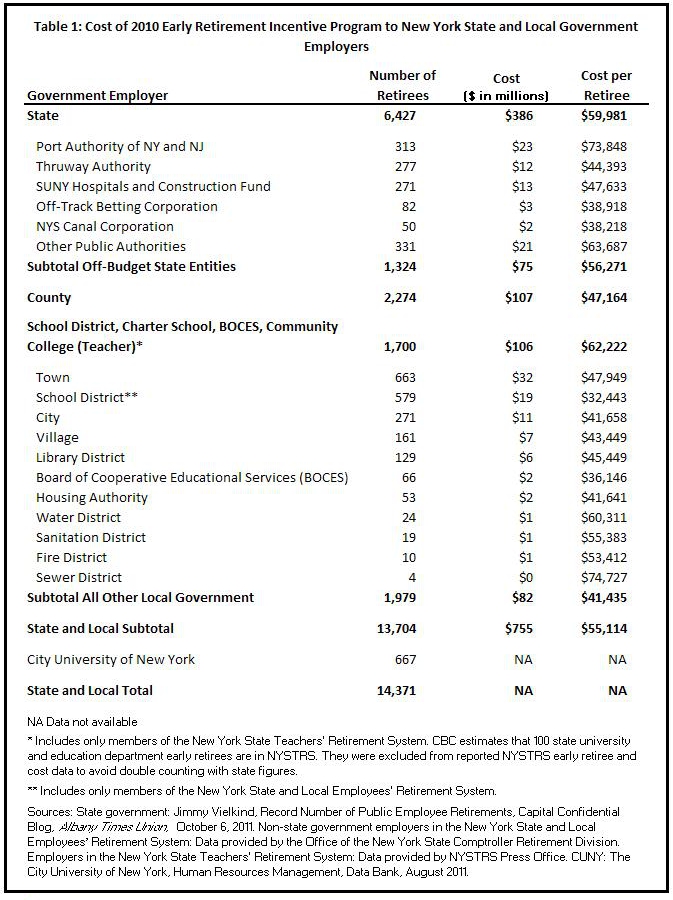

An estimated 14,371 New York State and local employees said yes to the ERI. The state government had 6,427 workers enroll, including 3,370 from the Executive branch, 2,941 from the Judiciary, the State University of New York, the State Comptroller’s Office and the Attorney General’s Office, and 116 from the State Insurance Fund.[5] (See Table 1.) The State Division of Budget recently reported that the total state cost with interest will be $385.5 million.[6] This figure is divided among the New York State and Local Employees’ Retirement System (ERS), the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System (NYSTRS), and state university employee 401k accounts.

An additional 1,324 members of the ERS from public authorities and other off-budget state entities took the ERI, including 313 from the Port Authority and 277 from the Thruway Authority.[7] These entities collectively owe $75 million for the added retirement benefits, with the Port Authority accounting for $23 million. Twenty-three county governments had 2,274 workers take the incentive, at a cost of $107 million.

Local government employers also owe about $106 million for 1,700 NYSTRS members who took the ERI.[8] Another 1,979 ERS members retired from other local governments, including cities, towns, villages, school districts, library districts, sanitation districts, water districts, fire districts, housing authorities and Boards of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES) at a cost of $82 million.

The City University of New York, whose members are in New York City retirement funds and TIAA-CREF, had 667 employees take the incentive.[9] Data was not available for the cost to CUNY.

The Savings

The bulk of the savings from the ERI is the reduction in direct payroll; additional savings come from employer payroll taxes for Medicare and Social Security. Most employers do not save on health insurance because retirees are generally eligible for the same plan until they qualify for Medicare. For state workers, the employer share of health insurance actually grows in retirement because unused sick leave credits offset the retiree share.

The savings estimates presented below are assumed to accrue over two years. This is the period over which early retirees’ positions are assumed to remain unfilled and the assumed average period for which they accelerated the timing of their retirement.

The key to calculating the payroll savings from the ERI is determining how many workers would have retired in the absence of an incentive. From fiscal years 2005 through 2009, an average of 3.0 percent of active members in the New York State and Local Employees’ Retirement System (ERS) retired.[10] If 3.0 percent had retired in fiscal year 2011, 16,019 state and local employees would have retired. According to the State Comptroller, 23,638 members of ERS retired in that fiscal year, 7,619 more than expected.[11] These are the induced early retirees. This compares to the 11,214 members of ERS who took the incentive.[12] Consequently, 67.9 percent of the ERI participants were presumably induced to retire by the ERI. If the same rate is applied to the 1,800 members of the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System (NYSTRS) and the estimated 690 members of SUNY’s defined contribution plan who opted for the ERI, an additional 1,692 retirees were induced for a total of 9,311.

In fiscal year 2011, new ERS retirees, aged 50 to 59 with 25 to 29 service years, reported a final average salary of about $67,360 and new NYSTRS retirees with 20 to 35 service years reported a final average salary of about $83,130.[13] Thus, in the first full year, the incentive saved $654 million in salaries. Including payroll taxes, the savings was $704 million. Assuming a 4 percent salary increase in the next year, the incentive saves $732 million in the second full year. Thus the two-year savings of $1.4 billion outweigh the cost of increased pension contributions of $755 million, for induced and non-induced ERI takers, by $681 million.

Alternatively, 7,761 state and local layoffs would have been necessary to achieve the same two-year savings as inducing 9,311 workers to retire.[14] If fully 9,311 state and local public employees were let go, government employers would have saved $817 million over two years, $136 million more than the ERI saved. As compared to the ERI, layoffs would have added to unemployment and had negative implications for employee morale. Additionally, significant layoffs may raise employer unemployment insurance taxes required to pay for unemployment benefits.

The net savings of the ERI are likely overstated because some early retirees have been replaced by new hires. The cost of a new hire includes wages, Medicare and Social Security payroll taxes, and healthcare insurance. Assuming a starting salary of $35,000, replacing 10 percent of the retirees reduces the two-year net savings from $681 million to $599 million. If half of the retirees are replaced, the savings falls to $272 million, and if 83 percent are replaced, the savings fall to zero. Although New York’s state and local government workforces have contracted by 1.8 percent since the ERI was enacted, public employers have offset some employee attrition with new hires.[15] A representative of the state court system reported that half of the ERI participants from the Judiciary had been replaced as of February 2011.[16]

Conclusions

The 2010 early retirement incentive in New York provided budgetary savings in exchange for a significant headcount reduction. At the time it was the only option available for labor savings. The next time an early retirement incentive is proposed, more options should be explored.

In particular, reforms to fringe benefits may have saved even more and would have prevented headcount reduction. If school districts outside New York City, which account for one-third of non-New York City state and local public sector workers, simply aligned their health insurance premium sharing plan with New York State government, they could have saved $220 million.[17] Eliminating New York State government’s rare practice of reimbursing Medicare Part B premiums would have saved $120 million,[18] and increasing health insurance premium sharing for retirees to 50 percent would have saved $315 million.[19]

Footnotes

- Chapter 105 of the Laws of 2010. Bill number A11144/S7909. Available at http://assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?default_fld=&bn=A11144&term=2009&Summary=Y.

- Members of the New York State and Local Employees’ Retirement System hired on or after January 1, 2010 must be 62 years of age with 10 years of service to retire. Members of the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System hired on or after January 1, 2010 must be age 57 with 30 years of service or age 62 with 10 years of service to retire.

- Lise Beng-Jensen, Early Retirement for State Workers: Money Saver or Costly Sweetener? Empire Center for New York State Policy, May 11, 2010. Available at http://www.empirecenter.org/pb/2010/05/ppwprint6051110.cfm.

- Press Release from Senator Andrea Stewart-Cousins, Senator Stewart-Cousins and Assemblyman Pretlow Pass Legislation to Save Money for Westchester Taxpayers, June 24, 2011. http://www.nysenate.gov/press-release/senator-stewart-cousins-and-assemblyman-pretlow-pass-legislation-save-money-westcheste

- Jimmy Vielkind, Record Number of Public Employee Retirements, Capital Confidential Blog, Albany Times Union, October 6, 2011.

- Freeman Klopott, New York Faces Pension Cost Bulge from Paterson’s Budget-Paring Incentives, Bloomberg News, October 24, 2011.

- Data for non-state government employers in the New York State and Local Employees’ Retirement System provided by the Office of the New York State Comptroller Retirement Division.

- Data provided by the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System Press Office. NYSTRS reported total cost of $112 million for 1,800 early retirees. Their spokesperson noted that “The counts and costs are not final at this time as member information is still in the process of being reviewed and validated.” CBC excluded an estimated 100 retirees from state universities and the State Department of Education to avoid double counting with state employee data. In fiscal year 2010, state budget documents report total SUNY headcount at 42,029, of which 3,087 are members of NYSTRS. These 3,087 were 1.6 percent of the state workforce in fiscal year 2010. Thus, CBC estimates that 1.6 percent of the 6,427 reported early retirees, or 100 retirees, are in NYSTRS. They were excluded from the NYSTRS data to avoid double counting with state data. A small number of State Education Department employees are also in the NYSTRS but could not be estimated. New York State Division of Budget, 2010-11 Enacted Budget Financial Plan, August 20, 2010, p. T-90. New York State Teachers’ Retirement System, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 2010, p. 112.

- The City University of New York, Human Resources Management, Data Bank, August 2011.

- Based on the number of new service retirements and the number of active members at the end of the prior fiscal year. Fiscal year 2010 was excluded due to the 2009 retiree buy-out program. Office of the New York State Comptroller, New York State and Local Retirement System Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Fiscal Years 2005 through 2009.

- Office of the New York State Comptroller, Annual Report to the Comptroller on Actuarial Assumptions, July 2011.

- To isolate ERS members, an estimated 100 members of the NYSTRS and 690 members of SUNY’s defined contribution Optional Retirement Plan were excluded. In fiscal year 2010, state budget documents report total SUNY headcount at 42,029, of which 3,087 are members of the NYSTRS and 21,000 are participants of the 401k-style Optional Retirement Plan. The former is 1.6 percent of the total state workforce and the latter is 10.7 percent. CBC estimates that 1.6 percent of the 6,427 early retirees are NYSTRS members, or 100, and 10.7 percent, or 690, are ORP members. New York State Division of Budget, 2010-11 Enacted Budget Financial Plan, August 20, 2010, p. T-90. New York State Teachers’ Retirement System, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 2010, p. 112. E.J. McMahon, Will Cuomo Truly Fix Pensions, New York Post, May 18, 2011. Available at http://www.nypost.com/p/news/opinion/opedcolumnists/will_cuomo_fix_be_radical_enough_MpJsDf50Gs89GdVeeutouK.

- Office of the New York State Comptroller, New York State and Local Retirement System Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2010, p. 133. New York State Teachers’ Retirement System, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 2010, p. 96.

- Calculation based on $35,000 salary for new hire in first year, 7.65 percent employer payroll tax, and $5,425 employer contribution to health insurance.

- New York State Department of Labor, Current Employment Statistics. Accessed September 14, 2011 and available at http://labor.ny.gov/stats/lscesmaj.shtm.

- Rick Karlin, Court Budget Stands Alone, Albany Times Union, February 10, 2011.

- Selma Mustovic and Elizabeth Lynam, School Districts Should Achieve Substantial Savings Following State Practices for Employee Health Insurance Premiums, Citizens Budget Commission, February 2, 2011.

- Maria Doulis, Simple but Significant: Savings from the Elimination of the Medicare Part B Reimbursement, Citizens Budget Commission, December 20, 2010.

- Elizabeth Lynam and Tammy Pels, Labor Costs in New York State: How to Save $1.2 Billion, Citizens Budget Commission, March 30, 2010.