What’s Different About Next Year’s City Budget

Last week, Mayor Michael Bloomberg presented New York City’s Financial Plan for the next four years, beginning with the current fiscal year 2012 (which ends June 30) through fiscal year 2016. The plan contains an important signal about the changing fiscal context in which the Mayor and the City Council must balance the budget.

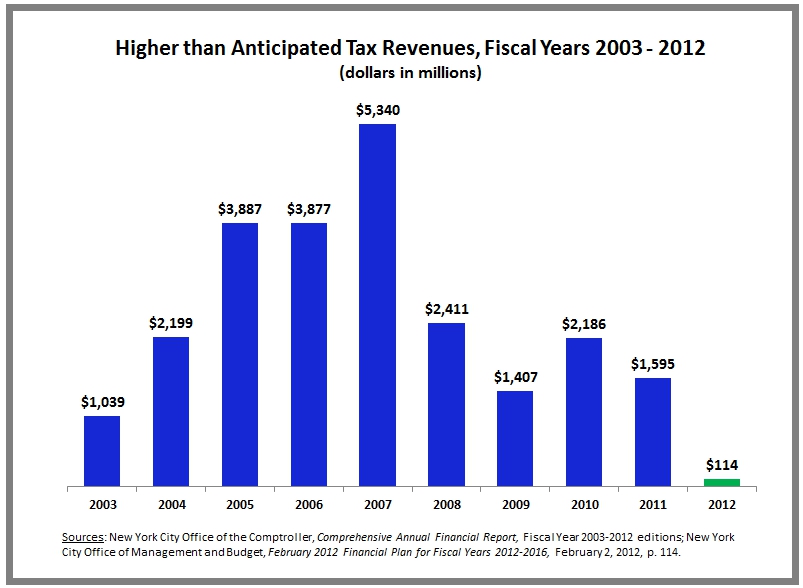

For the past decade, the City has benefited from tax revenues that were consistently and significantly larger than anticipated. In every fiscal year from 2003 to 2011, actual tax revenues were at least $1 billion above the sum originally budgeted.

As the economy surged in the mid-2000s, powered by a strong real estate market and Wall Street earnings, unanticipated tax revenues grew, reaching a high of $5.3 billion in fiscal year 2007. Even in recession years like 2009, conservative economic forecasting resulted in over $1 billion in additional tax revenues. These “surplus” taxes have been essential to balancing the budget and providing for additional spending and reserves to be drawn upon in subsequent years.

What’s different about this year? The latest budget update shows fiscal year 2012 tax collections are running only $114 million above the initially budgeted sum – a less than 0.3 percent increase on total tax revenues of $42.2 billion. For the first time in a decade, tax revenues are not exceeding expectations; they are just on target.

While the fiscal year is only half done, it is unlikely that the City will end the current fiscal year with unanticipated revenues of the magnitude to which its leaders have become accustomed. A look back at prior years’ plans indicates that outsized tax collections are usually apparent by mid-year. This time last year, the February 2011 plan indicated $1.1 billion in additional tax revenues for fiscal year 2011, and the year ended with $1.6 billion in higher than initially anticipated tax revenues. Similarly, the January 2010 plan recognized $1.7 billion in additional taxes for fiscal year 2010, and the City closed out the year with $2.2 billion in initially unanticipated higher tax collections.

Indeed, this year the City’s revenue forecast may actually be optimistic rather than conservative. Wall Street profits are running $7 billion below what was assumed when the budget was adopted; this has already resulted in a downward revision in personal income and business tax receipts, and presents a risk to revenues for the remainder of the year.

Without the extra tax revenues, the City is requiring agencies to make another round of cuts and find additional savings for this year and next. It is drawing down on its current year reserves, and relying on one-shot resources –$1 billion in revenues from the sale of taxi medallions as part of the outer borough taxi plan and $1 billion from the retiree health insurance trust fund – to balance the fiscal year 2013 budget. These non-recurring resources may get the City over the hump, but they are temporary solutions. If large unanticipated tax revenues are no longer a recurring part of the annual budget process, then the Mayor and the City Council will be obliged to consider fundamental changes in the City’s budget.

By Maria Doulis