A PEG by Any Other Name Would Smell as Sweet

Shakespeare’s immortal lines and City budget jargon rarely have much in common, but Mayor Bill de Blasio’s reluctance to include a Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG) in his financial plans calls to mind Juliet’s reflections on what it means to be a Montague. The Mayor voices heartfelt interest in finding ways to save money, but he does not want to call it a PEG or put such a name in his plan, at least in part because of its identification with prior administrations. Rather than follow Shakespeare’s tragedy, the Mayor would be better off giving the beloved a new name and presenting a financial plan that includes significant savings from new efficiencies in service delivery.

The Legacy of PEGs

PEGs trace their origins to the start of the City’s financial planning process during the 1975 fiscal crisis and were used by the four previous mayors, both Republicans and Democrats. Large deficits and apparently unlimited borrowing needs led to the City’s loss of access to credit markets in 1975. In response the State created the Municipal Assistance Corporation to borrow on behalf of the City and convert its short-term debt to long-term bonds, and it created an Emergency Financial Control Board that required the Mayor to prepare a three-year financial plan to identify borrowing needs and scale back deficits. This plan failed to achieve a balanced budget; in 1978 “Emergency” was removed from the Control Board’s name, and it became a more permanent oversight agency. One of its requirements was a rolling four-year financial plan that brought revenues and expenditures into balance at the end of the first four years and subsequently maintained that balance.

Mayor Ed Koch achieved a balanced budget one year ahead of schedule in fiscal year 1981, and the challenge then became how to maintain that balance. The planning process revealed that baseline projections based on current policies and trends indicated potential deficits, dubbed “gaps,” in future years, and Koch met the challenge by identifying steps to close those gaps in an element of the financial plan called the Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG). From 1982 to 2013 every financial plan included a PEG.

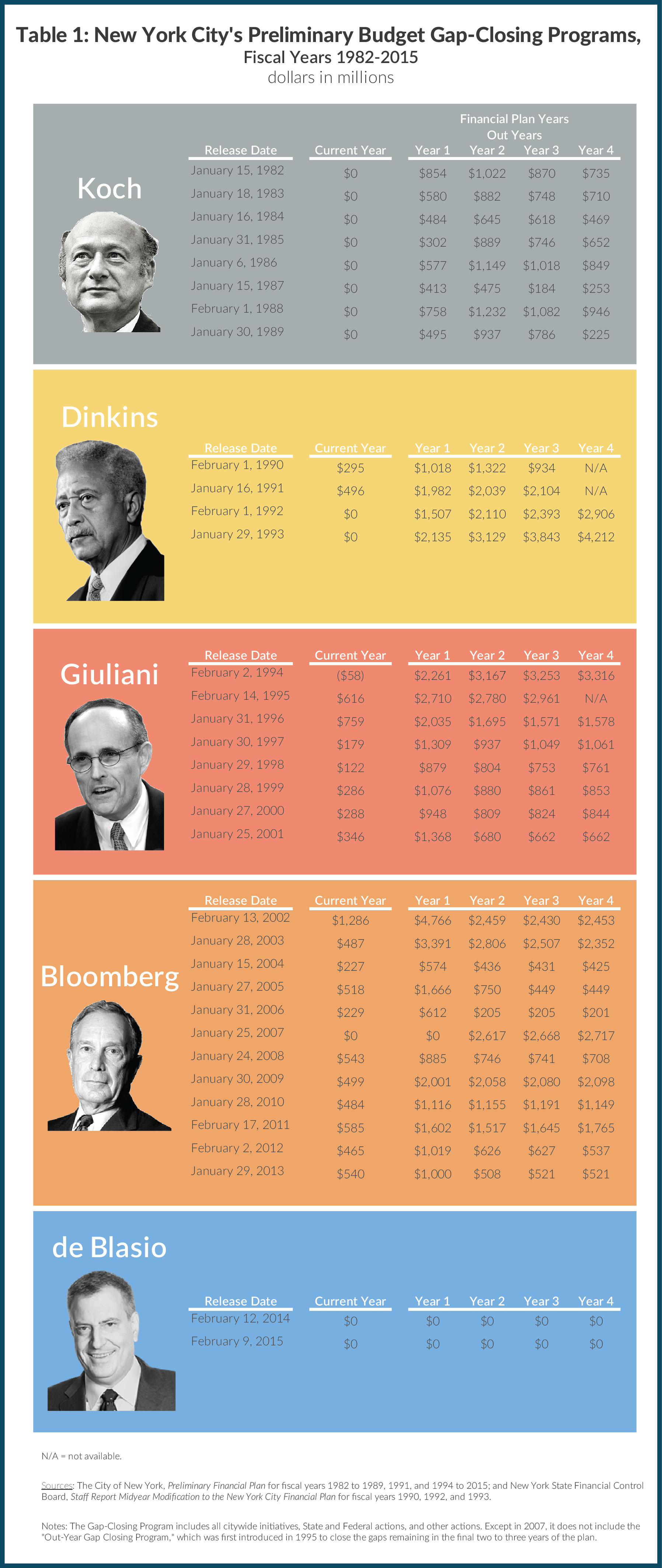

The City’s fiscal year begins on July 1, and the planning cycle begins with a preliminary financial plan and budget in the preceding January (or sometimes early February). The preliminary plan spans the current fiscal year and the next four years. The plans typically reveal substantial baseline gaps in the future years, and Mayors have included PEGs, along with other policy changes to show how the gaps can be closed or reduced. PEGs contributed to balancing the next year’s budget and showed the implication of those measures for future years’ budgets; in some plans additional measures to close the gaps in subsequent years were also identified and included in the PEG. Table 1 shows the annual amounts of the PEGs in each preliminary financial plan from January 15, 1982 to January 29, 2013.

A way to gauge the scale of PEGs is to consider the amount in the first of the four out years, identified as “Year 1” in Table 1. In the Koch Administration these PEG amounts varied from an initial $854 million to a low of $302 million, with the stock market crash in October 1987 leading to an increased PEG in February 1988. Mayor Dinkins faced a sharp recession and had PEGs in Year 1 of at least $1.0 billion and reached $2.1 billion in his last year. Mayor Giuliani inherited a difficult situation and the Year 1 PEGs in his first three preliminary budgets each exceeded $2.0 billion. As the economy improved and expenditures were contained, Giuliani’s Year 1 PEGs declined, but the recession in 2001 required a nearly $1.4 billion PEG.

The recession and the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks led to an unprecedented $4.8 billion PEG in Year 1 of Mayor Bloomberg’s first financial plan. Steady improvements in the economy lowered subsequent PEGs, and in the January 2007 plan soaring tax revenues led to a projected balanced budget for fiscal year 2008; no PEG was needed in Year 1, but Bloomberg included a PEG to address subsequent years’ gaps. Starting in 2008 the Great Recession required large new PEGs and Bloomberg’s last preliminary financial plan included a $1.0 billion PEG in Year 1. Implementation of the PEG led to Mayor de Blasio inheriting a balanced budget for fiscal years 2014 and 2015. According to the Comptroller’s Office, PEGs implemented from fiscal years 2008 to 2013 were responsible for more than $6.5 billion in savings in fiscal year 2014.1

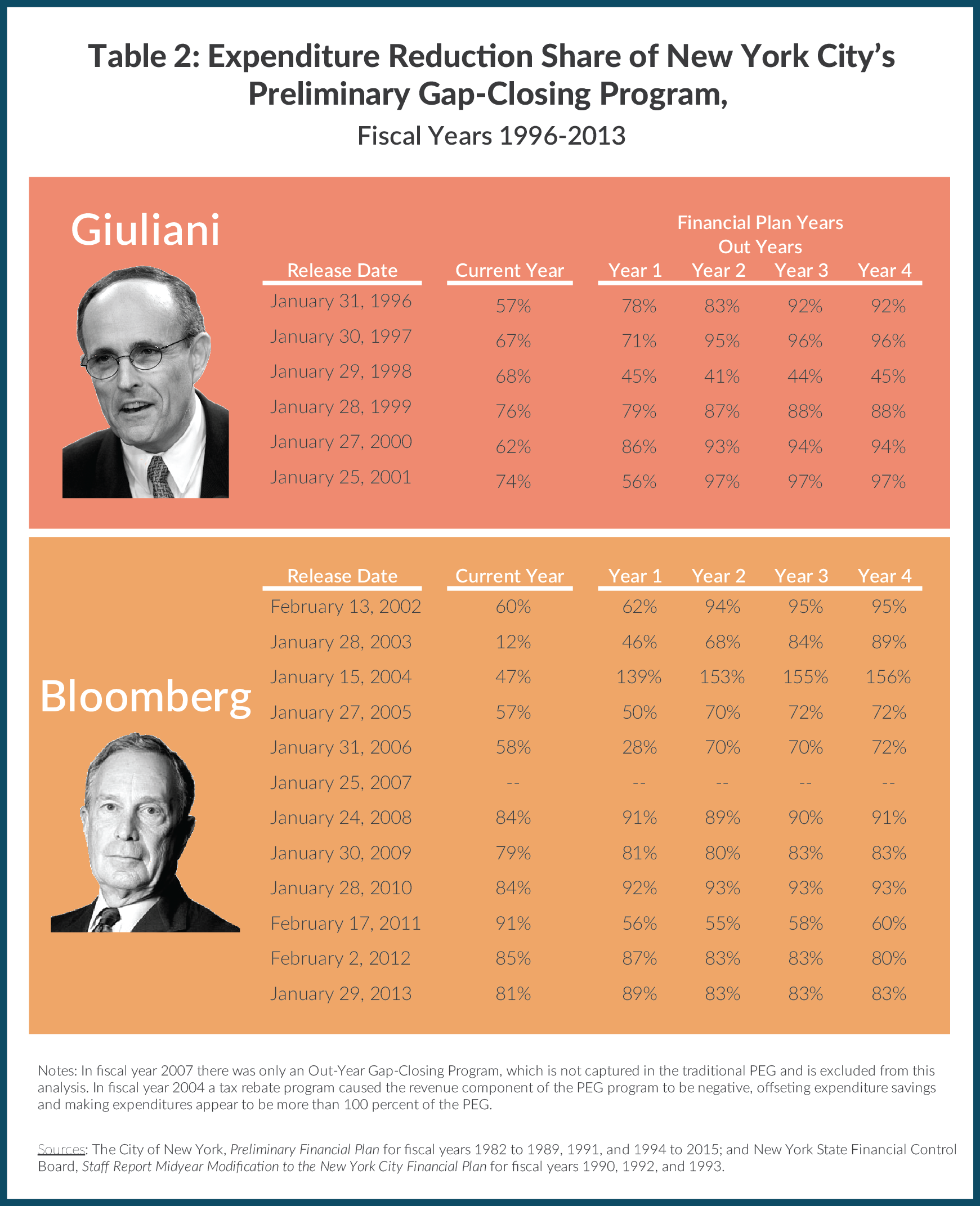

The PEGs designed by previous mayors have not relied exclusively on expenditure cuts. PEGs have included advocacy for new aid from the state and federal governments as well as City actions to increase revenues and reduce expenditures. Beginning in 1996 the financial plans adopted a format that identified all Citywide actions, agency actions, and State and federal actions in each PEG and further divided them between expenditure reductions and revenue enhancements. Table 2 shows the expenditure share of the total PEG for each year in the financial plan. In the Giuliani period the share in year one ranged from 45 percent to 86 percent. In the Bloomberg Administration the share was initially 60 percent, but was only 12 percent in January 2003 when tax increases were dominant. Beginning in January 2008 Bloomberg’s reliance on expenditure reduction increased. It is possible that the relatively heavy reliance on expenditure cuts in the later part of the Bloomberg Administration colored some officials' perceptions of PEGs and identified them with service cuts, making them less appealing to a new mayor elected on a platform of expanded government activity.

Time for a Renamed PEG

Mayor de Blasio is in a strong fiscal position. His February 2015 preliminary financial plan keeps the fiscal year 2015 budget balanced and achieves balance in fiscal year 2016 without a need for a PEG. Expectations of continued economic growth point to a positive revenue outlook, and multi-year collective bargaining agreements with most of the workforce that include modest pay raises help contain expenditure growth. Nonetheless, the financial plan identifies gaps exceeding $1.0 billion in fiscal year 2017 and approaching $2.1 billion in fiscal year 2019; an economic slowdown or recession would worsen the situation.2 Mayor de Blasio should begin planning for how to close these gaps and cope with any unexpected adverse conditions as well as new needs that may emerge. In addition, even in the absence of budget gaps, good management should include a continuous search for ways to achieve savings by making service delivery more efficient.

It need not be called a PEG, but the case for having a part of the financial plan include ways to improve the fiscal picture on both the revenue and expenditure sides of the ledger is strong. Mayor de Blasio’s next financial plan should be creative both in naming his strategy to reflect a progressive spirit and in identifying ways to keep the budget balanced and make service delivery more efficient in the future.

Footnotes

- City of New York, Office of the Comptroller, FY 2015 February Plan Presentation (February 24, 2015), http://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/FY_2015_Feb_Plan_Presentation.pdf.

- Michael Dardia and Rachel Bardin, “How Much to Bank on? When it Comes to Revenue Forecasting, Better Safe Than Sorry” (blog entry, April 13, 2015), http://www.cbcny.org/cbc-blogs/blogs/how-much-bank-when-it-comes-revenue-forecasting-better-safe-sorry.