Buoying EDC's Operating Budget

As New York City continues the hard work of balancing its budget, all agencies should scrutinize their operations to find efficiencies and redesign or eliminate programs that are not cost-effective. While the Economic Development Corporation (EDC) is not a City agency, it is an important arm of City government and should be part of the City’s effort to find savings. This is particularly important now; expansions of EDC’s responsibilities before the onset of the current fiscal crisis increased expenses and strained its operating budget. These pressures have likely been magnified by Covid-related reductions in its operating revenues and extraordinary costs stemming from the City’s pandemic response.

EDC’s recent decision to reduce service hours and recalibrate routes on NYC Ferry is a step in the right direction. The changes demonstrate how agencies can generate savings by redesigning programs to improve efficiency and provide budget relief. The changes will make ferry service more cost-effective to operate while ensuring that it remains a viable transit option. In the coming months, EDC should continue to identify ways to make its ferry operations more efficient, such as implementing dynamic fare pricing and delaying the launch of costly planned expansions.

What EDC Does and How it Funds its Operations

EDC was created in 1991 to lead the City’s economic development efforts and to improve the management of the City’s income-generating real estate properties and waterfront assets, which include the Brooklyn Army Terminal, the Hunts Point markets, and the cruise terminals. EDC retains the operating revenue generated by these properties and uses it to fund its core mission of promoting economic growth and competitiveness.1

Over time EDC has taken on other functions that traditionally have been under the purview of City agencies, such as the Department of Design and Construction and the Department of City Planning. EDC now manages many capital projects and leads an increasing number of City-initiated rezonings and redevelopment projects. More recently, EDC has taken on management of the NYC Ferry system in partnership with a private operator. City Hall frequently taps EDC to lead these efforts in part because the agency is not subject to the same procurement and oversight rules as other agencies, giving it greater flexibility in managing complex projects.

Increased Spending has Strained EDC’s Budget

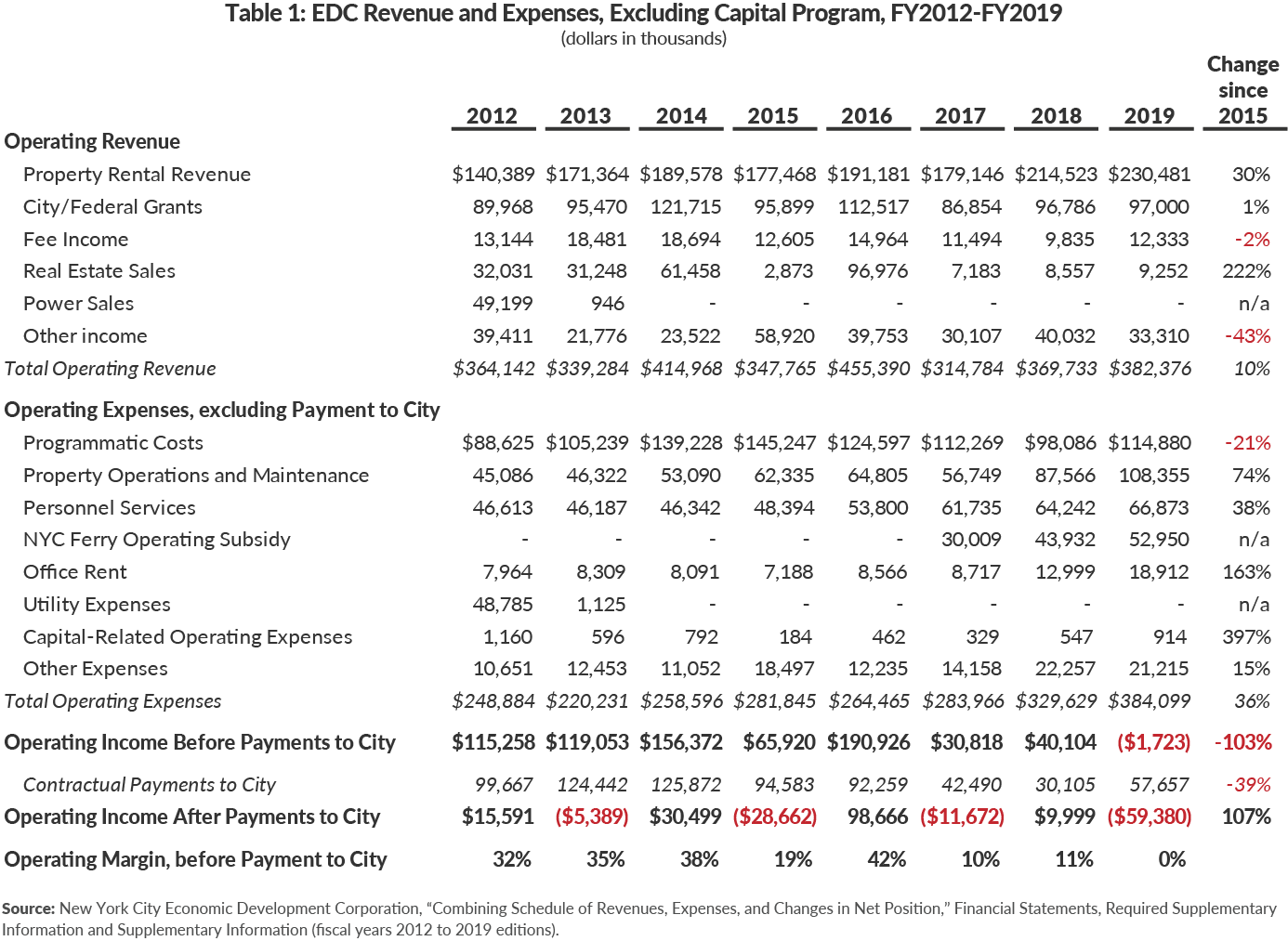

EDC’s core operations are funded through a combination of income from its real estate portfolio, grants from City and federal governments, and fees. Historically, these revenue sources have been more than enough to fund EDC’s operations and to allow EDC to remit a portion of its surplus to the City’s general fund. Between 2012 and 2014, EDC’s average annual operating surplus was $130 million–an average operating margin of 35 percent.2 (These figures exclude capital funding and expenditures that EDC manages on the City’s behalf. See Table 1 for the historical revenue and expenditure data cited in this report.)

Starting in 2015, however, EDC has grown less profitable as its revenue sources have failed to keep pace with its growing expenses. Between 2015 and 2019, operating revenue increased by $35 million, or 10 percent, to $382.7 million, while operating expenses grew by $102 million, a 36 percent increase, to $384.2 million. (A one-time spike in revenue in 2016 was attributable primarily to $97 million in non-recurring revenue from the sale of City-owned real estate.) The deterioration of EDC’s balance sheet in recent years culminated in 2019 when it closed the year with an operating loss of $1.8 million.3

Expense growth has been high in many divisions. The cost to operate City-owned assets grew $46 million (74 percent) between 2015 and 2019, though this growth was offset by a $53 million (30 percent) increase in rental income. Payroll costs also grew $18 million (39 percent), while rent expenses for the agency’s headquarters increased $12 million (163 percent) following EDC’s October 2017 decision to move into a newly renovated space at One Liberty Plaza. Rent costs may decline in future years, as the agency paid rent on both its old and new locations in 2019.

The most significant strain on EDC’s finances in recent years has been NYC Ferry operations. The de Blasio Administration’s decision to have EDC operate NYC Ferry starting in fiscal year 2017 resulted in rapid expense growth. EDC spent $53 million to subsidize NYC Ferry in 2019, the first full year of operations for the six initial routes.4 This does not include EDC’s costs for consultants, project management, and additional staff, which are included in EDC’s budget for property operations and maintenance, personnel services, and programmatic costs.

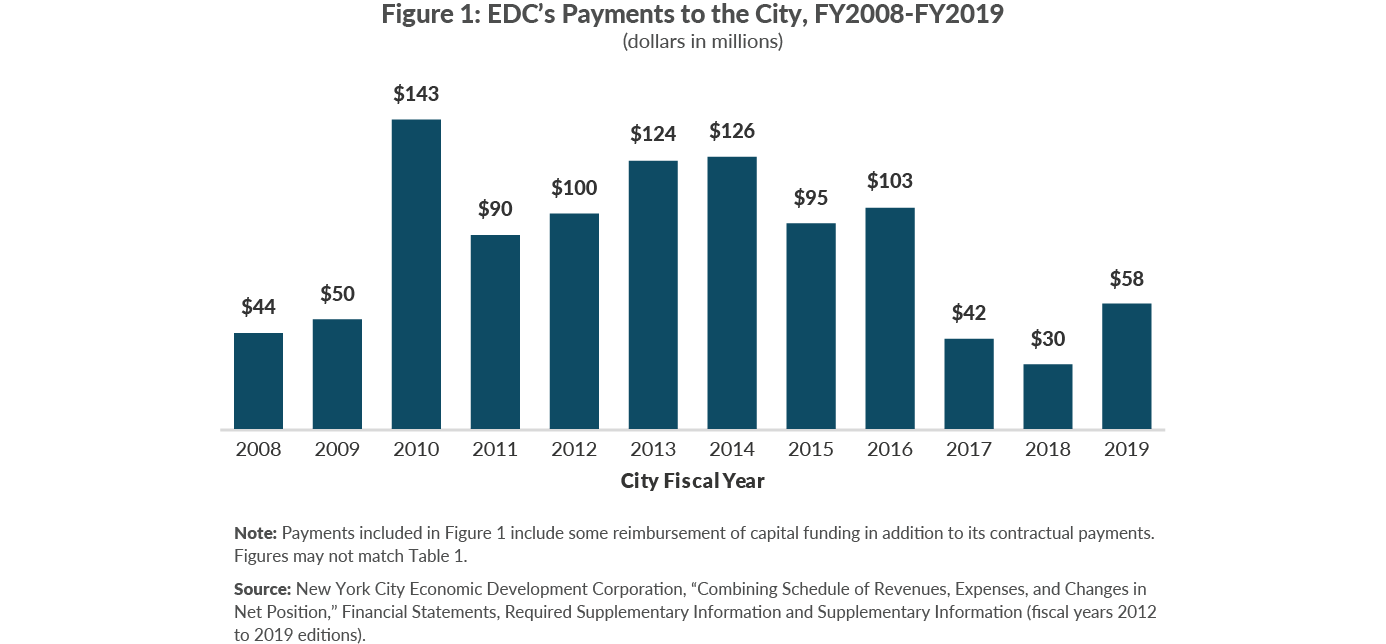

EDC’s Payments to the City’s General Fund

The negative impact of NYC Ferry on EDC’s balance sheet has also jeopardized EDC’s ability to share a portion of its surplus with the City’s general fund. Thanks largely to its profitable real estate portfolio, EDC’s assets have grown significantly over time. At the end of fiscal year 2019, EDC had $263 million in unrestricted net assets, including $116 million in unrestricted cash and investments.5 Under EDC’s management contracts with the City, the Mayor may request that EDC remit payments in lieu of property taxes and unrestricted net assets in excess of $7 million back to the City each year. In practice, the amount EDC remits is at the discretion of the Mayor.

These contractual payments have varied over time. (See Figure 1.) As the economy recovered from the 2009 recession, EDC increased its annual payments to the City from $44 million in fiscal year 2008 to $143 million in fiscal year 2010. These payments declined in fiscal year 2015 and again in fiscal year 2017 after the City and EDC agreed to reduce EDC’s payment to the City’s general fund to cover the costs of operating NYC Ferry. Following the launch of ferry system, EDC’s annual payments to the City have fallen to an average of $43 million per year.

EDC’s Fiscal Pressures Require Savings Efforts

EDC’s fiscal position will likely deteriorate as it weathers reductions in revenue across its portfolio. Like other transit systems, NYC Ferry has reduced service and is likely to experience significant reductions in operating revenue. EDC’s maritime portfolio revenue also is at risk; it generated nearly $84 million in income in 2019, much of it from lease payments from the operators of the Manhattan and Brooklyn Cruise Terminals, which have been effectively shut down as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. Commercial tenants in other EDC-managed properties also may seek to reduce or defer rent payments. In 2019 gross rental revenue for these commercial properties totaled $147 million. Several savings initiatives announced in the City’s Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2021 may actually impose additional costs on the agency. City officials have asked EDC to fund more environmental reviews that previously were to be funded by the Department of City Planning, and the EDC will also be cutting back on federally funded graffiti removal work.

To address the resulting fiscal pressure, EDC will need to reduce spending and draw on its net assets to balance its 2020 and 2021 budgets. EDC is fortunate to be able to draw on its unrestricted net assets as a de facto rainy day fund, but little will be left over to contribute to closing the City’s budget gap.

Accordingly, EDC has already begun to cut back on some programmatic spending to balance its budget. As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, EDC recently announced that it would further reduce ferry service and recalibrate routes to generate savings for the agency. Following a 30 percent reduction in service in March, EDC announced earlier this month that it would cut service by an additional 20 percent, end service at 9 pm, consolidate routes that previously provided overlapping service, and delay a planned expansion to Staten Island that was scheduled to launch in summer 2020. Agency officials estimated that these changes will reduce operating costs by approximately $10 million in fiscal year 2021.6

If needed EDC could generate additional recurring savings by modifying the ferry system’s fare policy and planned expansions. CBC previously recommended NYC Ferry charge higher fares on weekends and for noncommuters and not run or expand routes to Coney Island and Ferry Point that will require extraordinarily high subsidies. Neither were included in EDC’s initial savings effort.

The increased revenue and reduced expenses resulting from these changes would give EDC budgetary breathing room to maintain its core operations and to support the City’s efforts to promote economic growth during these economically and fiscally difficult times. The need to tap reserves and make changes to the ferry system, however, reflects fiscal management choices made in good times that now have resulted in the need to make more difficult choices in bad times.

Download Blog

Buoying EDC's Operating BudgetFootnotes

- EDC also staffs the City’s Industrial Development Agency and Build NYC Resource Corporation, which grant discretionary tax incentives and issue tax-exempt bonds on behalf of private companies and non-profits. The IDA and Build NYC cover their costs through fees charged to its borrowers and incentive recipients. EDC uses the fee income top pay staff costs, and surplus fee income is an additional funding source for EDC programmatic activities.

- New York City Economic Development Corporation, “Combining Schedule of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Net Position” Financial Statements, Required Supplementary Information and Supplementary Information (fiscal years 2012 to 2019 editions).

- EDC’s budget was balanced on an accrual basis consistent with generally accepted accounting principles. Non-operating revenue from investment income offset about $9 million of its operating losses. EDC also counted the receipt of ferry boats valued at $126 million towards its net position. The new ferries were purchased by the City using City capital funding and transferred to an EDC-controlled subsidiary at no cost and with no associated liabilities.

- This loss translates into a subsidy of $9.34 per ferry ride. See: Sean Campion, ”NYC Ferry Comparative Analysis,” Citizens Budget Commission (October 7, 2019), https://cbcny.org/research/nyc-ferry-comparative-analysis.

- EDC reported having $60.6 million in unrestricted cash and $55.4 million in unrestricted investments at the end of 2019. The remainder of the unrestricted net position consists of receivables for rent and loans and unspecified non-current investments. See: New York City Economic Development Corporation, “Statements of Net Position,” Financial Statements, Required Supplementary Information and Supplementary Information for Years Ended June 30, 2019 and 2018 (p. 13), https://www.abo.ny.gov/annualreports/PARISAuditReports/FYE2019/Local-LDC/NewYorkCityEconomicDevelopmentCorporation2019.pdf.

- Paul Berger, “New York City Reduces Ferry Service Amid Coronavirus Outbreak” Wall Street Journal (May 16, 2020), https://www.wsj.com/articles/new-york-city-reduces-ferry-service-amid-coronavirus-outbreak-11589581945.