Getting the Fiscal Waste Out of Solid Waste Collection in New York City

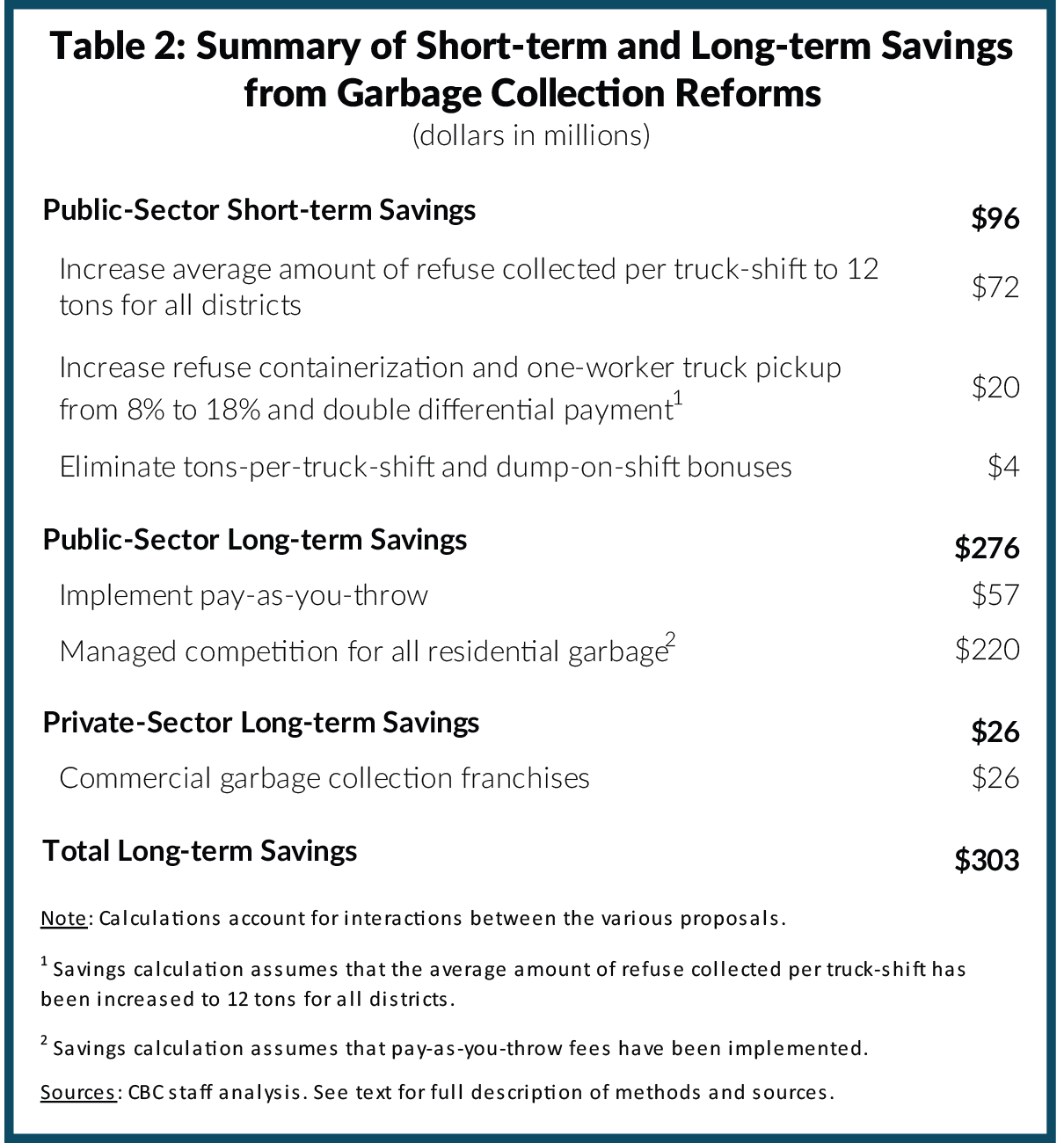

With a new mayoral administration, a new sanitation commissioner, and an expired contract with municipal sanitation workers, now is the time to change how New York City collects trash. New York City would save about $275 million annually by redesigning municipal waste collection policies. Addressing inefficiencies in the private trash hauling system would save businesses another $26 million annually.

This substantial savings can be partially achieved with modest changes in the public and private components of local waste collection and fully realized with more ambitious ones. Some needed reforms to the municipal Department of Sanitation (DSNY) collection practices should be incorporated in the next labor contract. Other reforms will take more time to implement; the Mayor and City Council should make this restructuring a goal and begin a multiyear phase-in.

In the short term, the City should implement three changes through negotiations with the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association (USA) and related City Council legislation:

- Promote flexibility to meet neighborhood needs. More flexibility should be permitted in the frequency of refuse collection, the scheduling of shifts, recycling practices, and the type of street litter basket. If routes were redesigned to increase the average amount of refuse collected per truck-shift from 10 to 12 tons, the City would save $72 million a year.

- Expand the use of large containers and automated trucks. DSNY’s fleet includes one-worker, flat-bed trucks for transporting large containers (dumpsters), but only 8 percent of refuse and 1 percent of recycling is collected in this manner. If DSNY expanded the use of one-worker, automated trucks from 8 percent to 18 percent, the City would save $20 million annually even if it doubled the related bonus payment to operators.

- Eliminate “unproductive” productivity bonuses. DSNY workers receive bonus payments for meeting targets for tons collected per truck-shift and for dumping their haul within a shift. However, meeting the criteria for these bonuses is a function of workers’ route assignments and the neighborhood characteristics, rather than a function of the workers’ productivity. Eliminating these bonuses would save $4 million a year.

The three reforms above would save $96 million annually, primarily by reducing the number of workers required; the reduction would be about 600 workers or 10 percent. A contraction of that magnitude could be achieved through attrition over two years.

In the longer term, a more transformative redesign of the public and private garbage collection system is needed. Four reforms should be phased in over a multiyear period:

- Implement financial incentives to reduce refuse generation. In other cities and in New York City’s commercial sector, garbage producers pay fees based on the volume of trash removed. Such charges discourage garbage creation and encourage reuse and recycling. By reducing garbage and increasing recycling, pay-as-you-throw fees would save the City an estimated $57 million annually.

- Introduce competition to promote efficient public waste collection. The high cost of DSNY waste collection relative to the private sector and other public agencies suggests exposing DSNY to competition could produce substantial savings. To start, the City should solicit public- and private-sector bids to collect smaller streams of waste now collected by DSNY, such as government agencies, schools, and street litter baskets. In addition the City should experiment with permitting private carters to compete for contracts to collect residential garbage in a few existing or modified sanitation districts. Over time if all DSNY collections were subject to competition, the City would save $220 million a year.

- Create franchises for more efficient commercial waste collection. While the high number of private-sector waste carters in the city has kept prices relatively low, the city’s “open” system for commercial trash collection creates overlapping routes and great variation in environmental performance. A franchise system for commercial garbage would limit the number of carters allowed to operate in a given area, thereby reducing truck congestion and improving the efficiency of operations. The savings to the private system would be $26 million annually.

- Diversify capacity for snow removal. Unlike other cities, New York relies almost entirely on its sanitation department for snow removal. That hinders the City’s ability to implement productivity savings to garbage services; any reduction in the full-time workforce is deemed a threat to snow operations. So the limited number of snow events does not impact year-round staffing decisions at DSNY, the City should diversify its snow removal workforce to include other public employees, private contractors, and retired DSNY employees.

Key Findings from CBC's Previous Reports

This report is the third in a recent series by the Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) intended to help improve municipal solid waste management. In May 2012 CBC issued Taxes In, Garbage Out, an analysis of the high fiscal and environmental costs of New York City’s predominant method of garbage disposal – long-distance shipping and landfilling.1 About three-quarters of waste managed by the municipal Department of Sanitation (DSNY) travels hundreds of miles to landfills in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Ohio, and South Carolina. CBC recommends diverting more trash from landfills through local investments in modern energy conversion facilities. Diverting more trash to local energy recovery plants would have multiple benefits: avoided expense and carbon emissions associated with transporting and burying garbage in landfills; greater production of energy using non-fossil fuels; increased metal recycling (extracted before conversion); and preserved landfill capacity.

The City has taken some actions along the lines CBC recommended. In August 2013 the City signed a 20-year contract with a private firm, Covanta, to transport 800,000 tons of garbage from marine transfer stations in Queens and Manhattan to waste-to-energy plants in Niagara, New York and Chester, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia.2 If executed as planned, with transfer station operations projected to begin in 2015 in Queens and 2016 in Manhattan, the share of DSNY-managed trash converted to energy would triple from 10 percent to about 30 percent. However, long journeys for New York City trash would continue; Niagara is a 455-mile rail-trip from the city, and Chester is 107 miles away. Locally over the next three years the City is expanding capacity to convert food waste to natural gas at the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment facility from 600 tons to 76,500 tons annually.3 The City also solicited proposals in March 2012 for additional investments in emerging waste conversion technologies within 80 miles of the city but has not disclosed or acted on any responses.

In May 2014 CBC released an analysis focusing on refuse collection practices.4 12 Things New Yorkers Should Know About Their Garbage found collecting and disposing of garbage is twice as expensive for DSNY ($431 per ton) as it is for the city’s heavily unionized private-sector waste carters ($185 per ton). DSNY serves residential buildings, government agencies, and many nonprofit facilities, and more than 250 private-sector waste carters serve city businesses.5 Much higher diversion rates (that is, the share of refuse recycled) in the commercial sector, 63 percent versus 15 percent for DSNY waste, account for part of the differential; however, excluding disposal expenses, the average cost of collecting one ton of refuse and recycling in the city is $307 for DSNY and $133 for private-sector carters.

The analysis also found that collection costs are much lower for public agencies in other big cities. While comparisons of public sector waste management are difficult because cities divide responsibilities differently between the public and private sectors, the latest available data show the public-sector cost of collecting a ton of refuse was $74 in Dallas, $83 in Phoenix, $182 in Washington, D.C., $231 in Chicago, and $251 in New York City.6

The May 2014 report identified these reasons for the high costs at DSNY.

- New York is one of only a few large cities that pay for trash collection entirely out of general tax revenue. With no charges on customers, the system fails to connect the amount of non-recyclable refuse generated to the price paid to have it collected and disposed. Municipalities with volume-based user fees, such as San Francisco and Toronto, have higher recycling rates.

- DSNY has high compensation costs. DSNY’s practices are labor-intensive; only 8 percent of refuse and 1 percent of recycling is collected in large dumpsters with automated, flat-bed trucks. Another 4 percent of refuse and 4 percent of recycling is collected in small dumpsters with semi-automated, front-loading trucks. The remainder must be hand lifted by a sanitation worker. Compensation for that physical labor, comprising direct wages and fringe benefits, begins at more than $100,000 and averages more than $150,000 annually. Adding to DSNY costs, labor is not efficiently allocated; collection routes in many areas typically do not result in a full truck. Impediments to more efficient collection include minimum refuse collection frequency of twice per week, rigid eight-hour shifts, and limited night collections.

- Inflexible recycling collection schedules and low recycling rates produce half-empty recycling trucks. New York City residents recycle 15 percent of waste, capturing only half of designated recyclable material. Despite neighborhood rates that range from 5 percent to 26 percent, recycling is collected once per week citywide. Mandated separation of recycling into two waste streams – paper/cardboard and metal/glass/plastic – and long travel times to recycling processors further drive up costs. In fiscal year 2012, DSNY spent $629 per ton to collect recyclable material, more than double the cost for refuse.

- Heavy reliance on DSNY for snow removal is unique among big cities. The City relies almost entirely on DSNY employees for snow removal, necessitating higher workforce levels for year-round positions and generating high overtime costs. Other large cities assign snow removal to a broader group of public and private workers.

- Commercial garbage collection routes overlap with each other and with DSNY. Private waste carters may serve any part of the city, leading to routes that overlap with other carters as well as DSNY in residential areas. While the high number of private carters serving businesses has kept prices low and minimized corruption, the current system is inefficient and fosters traffic congestion and air pollution.

Recommendations

The actions needed to make waste collection in New York City more efficient can be divided into two groups. The first are shorter-term measures that can be implemented through collective bargaining and City Council legislation; an opportunity for immediate action is available because the contract with the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association (USA) is expired and currently under negotiation. The second are longer-term reforms that require mayoral leadership and City Council cooperation; they should be phased in and require several years for full implementation.

Short-term Savings

Mayor de Blasio and his Commissioner of Labor Relations have been negotiating contracts with unions representing the municipal labor force. Simply following the pattern of the contracts already negotiated would be a missed opportunity for both the City and the sanitation workers.

The new USA contract should change key provisions to enable greater efficiency; in exchange, a part of the savings could be applied to fund raises above the pattern. Such “gainsharing” is an opportunity for substantial taxpayer savings along with higher wages for the sanitation workers. Because many aspects of DSNY operations are governed by city law, support from the City Council is essential to achieving productivity savings. Negotiations with the USA should include garnering union support for changes to local laws that hinder reforms.

The City should implement the following three reforms in the short term: 1) promote flexibility in service arrangements to meet neighborhood needs; 2) expand use of automated trash collection; and 3) eliminate unproductive “productivity” bonuses. The second and third actions can be implemented through collective bargaining, while the first action requires cooperation from the City Council as well as union support. These short-term recommendations would save $96 million annually and permit a 10 percent reduction in the sanitation workforce, which could be achieved over two years through attrition.7

-

Promote flexibility in service arrangements to meet neighborhood needs

Rigid work rules hamper innovation and the efficient allocation of resources in sanitation services. All neighborhoods have recycling collections once per week; refuse is collected either two or three times per week during a six-day workweek; routes cannot cross district borders; and collections are almost always scheduled during eight-hour, daytime shifts. The product of that rigidity is DSNY trucks that are not full at the end of a shift. The problem is particularly acute in the less dense areas of the city. While a full DSNY truck can carry 12.5 tons of refuse, the average haul in eastern Queens and Staten Island is only eight tons per shift.8 Citywide, sanitation workers collect an average of 10 tons per shift.

Greater flexibility would reduce the number of garbage trucks on the road, producing financial and environmental benefits. With respect to refuse collection, altering its frequency and redesigning the routes to ensure every truck-shift picks up at least 12 tons would allow an 8 percent reduction in the number of sanitation workers and save $72 million annually.9

Achieving that goal requires City Council action as well as reforms to the USA collective bargaining agreement. Flexibility is needed in scheduling collections during workdays, in frequency of refuse collection, and in frequency of recycling collections.

Permit flexibility in the scheduling of collections

Sanitation workers typically work five days per week, eight hours per day, Monday through Saturday, either 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. or 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. If their work falls outside these parameters, they receive a differential payment. These include 10 percent extra pay for night shifts and double pay for Sundays.10 Worker shift times and differential payments are subject to collective bargaining.

Commercial garbage collection is more flexible and more likely to occur at night when the streets are less congested. Fully 85 percent of commercial collection in New York City happens at night, compared to only 19 percent for DSNY.11 DSNY experience suggests that night collections take about 9 percent fewer hours for equivalent routes.12 While late-night collections should be avoided due to noise considerations, DSNY shifts should be able to vary and include some evening hours when traffic delays might be less frequent.

In addition, while overtime pay rates should be required for hours in excess of 40 per week, shifts of 10 or 12 hours should be permitted if they facilitate more efficient collections. In areas far from transfer stations, switching from an 8-hour shift five days per week to a 10-hour shift four days per week may result in fuller trucks and less time traveling back and forth from sanitation garages to dump the hauls.

Reduce certain neighborhoods to once-per-week refuse collection

Unlike other large cities, every neighborhood in New York City receives a minimum of twice per week refuse collection. The irrationality of citywide standards among such diverse areas is illustrated by this fact: Staten Island has a greater share of single-family homes than San Francisco, Boston, and Los Angeles, but none of these cities offer more than once-per-week refuse collection.13 Permitting once-per-week refuse collection in certain areas of the city would not be a hardship and would reduce the costs to taxpayers. Under current practice, Staten Island and eastern Queens – the least dense areas of the city – are the least efficient. In these areas workers need more than two hours to collect one ton of refuse, compared to only 1.3 hours in the Bronx.14

One obstacle to once-per-week refuse collection is the presence of a few large, multiunit buildings in low-density neighborhoods, but this is easily overcome. All large apartment buildings could be provided more frequent collections via specialized routes without serving the far more numerous single-family homes in the neighborhood on the same schedule. Alternatively, large residential buildings in lower-density neighborhoods may be good candidates for larger container service. If space permits, these buildings could be removed from the regular curbside route and serviced less frequently by an automated container truck.

As an alternative to eliminating one day per week of refuse collection, frequency standards could be based on cycles other than “times-per-week;” for example, every third or fourth day for refuse collections regardless of the day on which the cycle falls (including Sundays).

Allow flexibility in recycling collection

Because neighborhoods vary widely in their recycling practices, rigid citywide once-per-week recycling collection for all types of recyclables creates great inefficiencies. While less-frequent collection in some areas might be an interim measure, the best long-run solution is to increase recycling rates in all areas. The City should actively pursue this goal through a variety of measures. In addition to the pay-as-you-throw incentives discussed below, a promising strategy is “single stream” or “commingled” recycling collection that does not require residents to separate types of recyclables. Economically sensible single stream collection requires that the benefits – higher recycling rates and lower collection costs – exceed the increased costs of sorting the materials after collection and the accompanying degradation of the quality and value of some (mostly paper) recyclables. While most recycling facilities in the city process only paper and cardboard or only metal, glass, and plastic, a recycling facility owned by Action Carting in the Bronx and the City’s new recycling plant in Sunset Park, Brooklyn use infrared technology to sort different types of plastics and paper.15 The City Council should amend city recycling laws to permit the testing and potential expansion of single stream recycling.

Provide innovative street baskets

The current system for emptying street litter baskets is labor-intensive and often inadequate for managing waste in heavily-trafficked areas. In fiscal year 2012, DSNY assigned nearly 21,000 truck-shifts for street baskets; on average workers collected only 3.3 tons during a shift.16 Additionally, many street baskets overflow and leak, creating unsanitary and aesthetically displeasing streetscapes. In some areas, the City Council has allocated discretionary funding to replace metal baskets with larger, plastic containers that have closed sides; the Council should go further.

Within New York City, a few Business Improvement Districts that supplement DSNY service, including the ones for Chinatown, Downtown-Lower Manhattan, and Times Square, have purchased solar-powered “BigBelly” containers.17 DSNY also plans to pilot these containers on one route in Brooklyn. With the ability to compact garbage, these high-tech bins have five times the capacity of the standard DSNY bin, and crews can monitor the volume of trash remotely to determine when to empty the bin.18 Other cities have invested in street bins with large storage capacity hidden underground. In the European cities of Amsterdam and Zurich, trucks use cranes to lift street level containers and concrete storage bins attached below.19 Barcelona has also invested in “smart” garbage bins that alert workers when they are full.20 The City Council and DSNY should work together to implement more efficient ways to collect pedestrian trash.

-

Expand use of automated trash collection

Most DSNY garbage collection requires demanding physical labor; on an average curbside refuse collection shift, a worker will hoist five tons of garbage into the truck.21 Only 12 percent of refuse and 5 percent of recycling is collected by automated trucks with mechanical features to lift and dump containers.22 Apparently as a result of this constant heavy lifting and operating in congested traffic conditions, absence rates for injuries in the line of duty are higher for New York City sanitation workers than for police officers.23

Greater use of automated trucks would reduce injury rates and improve productivity. DSNY’s truck fleet includes one-worker, “Roll-on/Roll-off” flat-bed trucks for transporting large containers (dumpsters or compactors) and two-worker “EZ Pack” automated, front-loading trucks for emptying smaller containers. In fiscal year 2012, 8 percent of refuse and 1 percent of recycling was collected with Roll-on/Roll-off trucks, and 4 percent of refuse and 4 percent of recycling was collected with EZ Pack trucks. The use of these trucks should be expanded.24

The City and the USA should agree to expand refuse collection in Roll-on/Roll-off trucks and increase the existing differential for operating these trucks. If DSNY were able to increase the rate of refuse collection with Roll-on/Roll-off trucks from 8 percent to 18 percent, the annual savings would be $22 million. If the bonus for the single truck driver was doubled from $96.53 to $193 per shift, the annual savings would still be $20 million.25 If workers have a greater stake in these savings, union representatives and workers themselves would be motivated to suggest where they can be implemented. DSNY should also consider providing annual bonuses to supervisors based on their employees’ productivity savings.

In addition to expanding use of Roll-on/Roll-off trucks, DSNY should also introduce automated, side-loading trucks for curbside refuse collection. These trucks have a mechanical arm to pick up garbage bins, allowing a single worker to drive and operate them. Because the use of such trucks requires curb access, DSNY should first introduce them into less dense neighborhoods with light curbside parking. Usage in more-dense areas may also be possible if managers coordinate garbage pickup with street cleaning – another DSNY responsibility – when curbside parking is not permitted.

-

Eliminate unproductive “productivity” bonuses

The USA contract includes multiple incentive payments that theoretically motivate greater productivity. However, two of them – the bonuses for meeting tons per truck-shift targets and for dumping on shift – are primarily dependent on the characteristics of the route rather than on worker behavior. The number of tons collected on a shift is largely determined by the area’s housing density. While the tons per truck-shift targets vary by neighborhood, the nature of route assignments limits how much more a worker can collect by moving more quickly. In addition, in recent years these bonuses have been paid even when targets are not met, with the justification that the shortfall is beyond the worker’s control due to less waste generation by residents. The USA contract stipulates that bonuses are paid as long as districts abide by agreed-upon routes and do not exceed a certain number of truck-shifts.

The dumping-on-shift bonus was implemented more than a decade ago to ease the transition from dumping garbage in Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island to using a network of transfer stations to prepare trash for long-haul export. While the bonus was initially successful in increasing the share of hauls collected and dumped within the same shift, today receipt of the bonus is primarily determined by the route’s proximity to a transfer station, a factor beyond the worker’s control. Both of these bonuses should be eliminated; the estimated annual savings would be $4 million.26

Long-term Redesign

The next contract with sanitation workers is an opportunity for immediate savings, but the greatest benefits to taxpayers depend on longer-term redesign of current waste collection practices. New York City’s future waste collection system should be reconfigured based on four elements. Together these reforms would save more than $300 million annually.

-

Financial incentives to reduce refuse generation

The current system of funding collections through general revenue appropriations gives residents the impression the service is “free” and provides no incentive to produce less waste or recycle properly. Municipal policy should incorporate financial incentives to reduce waste.

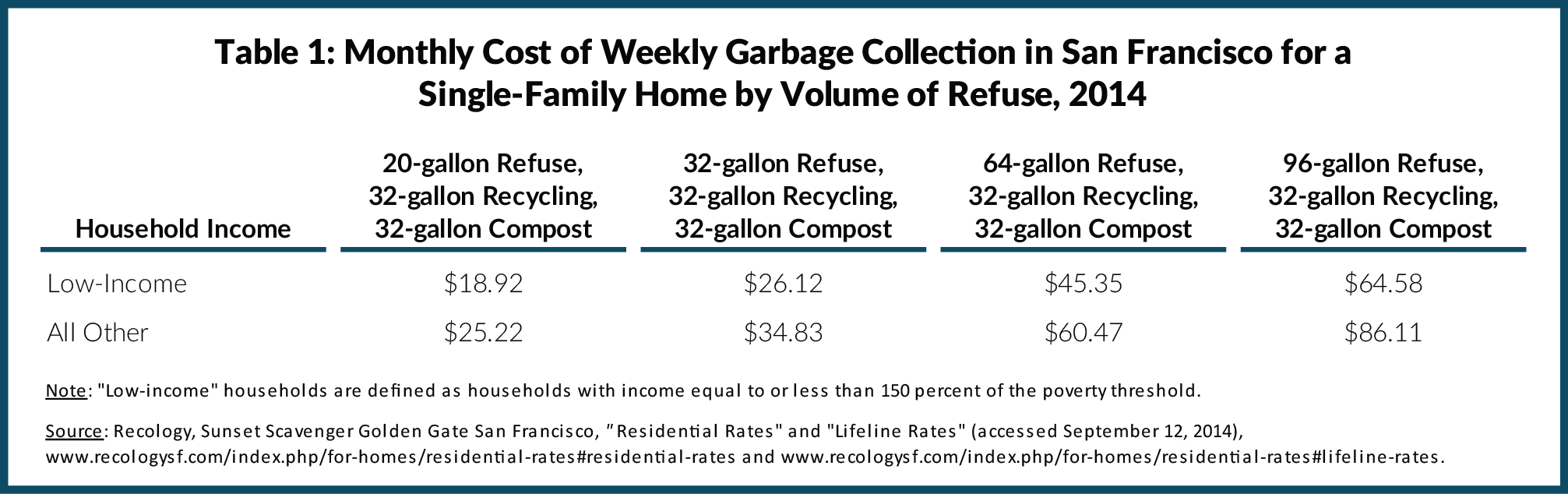

Other cities have created such financial incentives through pricing arrangements known as pay-as-you-throw (PAYT).27In cities that use containers, PAYT systems typically vary prices based on the size of the refuse container while offering unlimited, free collection of recyclables. Notably San Francisco and Seattle have PAYT systems with strong incentives to produce low amounts of non-recyclable or compostable refuse. For example, the monthly price for single-family homes in San Francisco is a base charge of $5, plus $2 for each 32-gallon recycling bin, $2 for each 32-gallon compost bin, and $26 for each 32-gallon refuse bin.28 Residents can also choose a 20-gallon refuse bin for $16. Residents with income less than or equal to 150 percent of the poverty threshold receive a 25 percent discount.29 Thus, a low-income household with the smallest refuse bin pays $19 per month, while a higher-income household with a 96-gallon refuse bin pays $86. (See Table 1.) The charge for apartment building owners is based on the volume set out, the frequency of collection, the diversion rate, and the number of apartment units.30 A single private company, Recology, is responsible for garbage collection in San Francisco.

In Berlin, Germany, residents pay variable fees based on bin size and the frequency of collection.31 For weekly collection, a 60-liter (16-gallon) refuse bin costs 267 euros ($346) annually, while a 240-liter (63-gallon) bin costs 407 euros ($528).32 If residents periodically require additional capacity, they can purchase bags called Mullsackes for 6 euros ($8) each.33 Recycling is free, but Berliners pay for organics collection; for example, a weekly 60-liter (16-gallon) organics bin costs 125 euros ($162) annually. These fees are set and collected by Berliner Stadtreinigungsbetriebe (BSR), a public utility owned by the city-state of Berlin responsible for solid waste management.34

In San Francisco and Berlin, PAYT charges are assessed at the building level, limiting the impact on any one household in a large apartment building; however, other cities require all households to purchase government-sanctioned bags or special tags to be affixed to the garbage they generate. In Zurich, Switzerland residents must buy “Zuri-Sacks” for non-recyclable refuse at local retailers. The bags range from 0.85 Swiss francs ($0.91) for a 17-liter bag (4.5-gallon) to 5.7 Swiss francs ($6.11) for a 110-liter bag (29-gallon).35 Residents may also subscribe to weekly organics collection from March to December and biweekly collection in January and February; for example, collection for a 140-liter (37-gallon) container costs 180 Swiss francs ($193) per year.36 In Seoul, South Korea, local retailers also sell government-mandated garbage bags, although the prices are lower and the bags are smaller than in Zurich. In one South Korean district, bag prices range from 100 won ($0.10) for a 5-liter bag (1.3-gallon) to 880 won ($0.85) for a 50-liter bag (13-gallon).37 Recycling can be placed in any plastic bag, but food waste must be separated and placed in government-sanctioned bags.

Three problems raised by PAYT are the economic impact on low-income households, the danger of illegal dumping, and the perception of a new tax. Measures are available to minimize these problems. First, the regressive nature of PAYT fees can be addressed by establishing a separate schedule of fees for lower-income households, the approach used in San Francisco. Alternatively, the City could give a limited number of free bags to households below a certain income threshold, while also targeting educational campaigns to neighborhoods with low diversion rates.

To ensure a PAYT system does not result in illegal dumping, the City should enact steep penalties and assign enforcement agents. In Zurich residents face a fine of 200 Swiss francs ($214) for illegal dumping.38 Other municipalities with PAYT have also allowed large bulky waste to remain free to dispose. Some sly New Yorkers will inevitably invent ways to avoid compliance and payment; vigilant enforcement with ongoing monitoring to identify evasion practices will be required.

To prevent the new fees from being an added tax burden, the City could issue annual household rebates or tax credits. For instance, households in Toronto pay annual fees for garbage bins but receive an offsetting rebate.39 With the rebate, low-trash producers in Toronto effectively pay little for garbage removal. For multiunit buildings, managers pay CAD$197 ($178) annually per unit for 1.9 cubic yards of refuse disposal, a weekly average of 7 gallons, and receive a rebate of CAD$185 ($167).40 Each additional cubic yard of refuse, or an average of 4 gallons per week, costs CAD$13.67 ($12.35).

The new PAYT fees should also apply to collections from nonprofits served by DSNY. The same logic applies to nonprofits as to households – consumers should have an incentive to waste less and recycle more. The City could also consider including sanitation services in government agency and public school budgets, as is already the case for the City’s Housing Authority. Doing so would require a cost accounting of garbage removal for each government agency, which would clearly identify low- and high-generators of garbage. As an incentive to produce less waste, the City could allow agencies to retain and reallocate savings from reducing trash below a benchmark.

Along the same lines, in 2013 City Councilmembers introduced two different bills to implement a plastic bag fee. One bill would impose a 5 cent deposit and refund for plastic bags; the other would implement a 10 cent fee on plastic and paper bags.41 Under the latter proposal, the revenue would be retained by the retailer.

A study of U.S. municipalities with PAYT charges found that average refuse levels fell 17 percent after implementation, with refuse production down 6 percent and the remainder due to increased diversion.42 If New York City achieved a similar reduction in refuse and increase in recycling, the City would save $57 million annually.43 The increase in recycling would also have significant environmental benefits by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution from collection truck routes no longer needed and from avoided landfilling.

-

Managed competition to promote more efficient public waste collection

Responsibility for trash collection is divided between DSNY and heavily unionized private-sector waste carters. DSNY picks up garbage from residential buildings, government offices, schools, large nonprofits (e.g. universities and religious organizations), and street litter baskets; private carters mostly collect from businesses but also supplement DSNY service for some nonprofits and street baskets. While public- and private-sector crews often cross paths, they do not compete. Despite some differences between trash collected by DSNY and private carters, the ability of private-sector crews to operate at less than half the cost at DSNY – $185 per ton versus $431 per ton – suggests competitive pressures could significantly reduce current public garbage collection costs.

This conclusion is not unique to New York; numerous studies have shown competitive contracting for garbage collection to be much less expensive than direct public provision. Studies in the 1980s and 1990s in the United States showed savings greater than 20 percent, and an analysis of Canadian cities found that contracting reduced costs 31 percent.44 Among the municipalities relying on competitive contracting, several allow the public-sector agency to compete with private firms for contracts covering all or portions of the city, a strategy known as managed competition. That approach prevents municipalities from becoming unduly dependent on the private sector and gives the public-sector workforce the opportunity to stay in business. The public agencies have inherent advantages, including experience, existing equipment, and tax-exempt status.

Using managed competition, cities such as Phoenix, Arizona; Charlotte, North Carolina; Jacksonville, Florida; and Indianapolis, Indiana have produced savings of 20 percent to 40 percent.45 Chicago recently used managed competition to finance an expansion of the number of households receiving recycling service from 260,000 to 600,000.46 Prior to implementation, the City found that private collectors could pick up recycling for $2.75 per cart per month, compared to public costs of $4.77.47 To become more competitive, public recycling crews changed work rules and reduced costs per cart 24 percent to $3.64. As a result of that cost reduction and the allotment of contracts to private carters in four of six service areas, the costs of Chicago’s recycling program are 37 percent less than projections without the competition.48 Similarly, in both Charlotte and Phoenix, after initial losses of some districts to the private sector, the public sector initiated labor management reforms that resulted in subsequent winning bids and eventual dominance of the business.49

New York City should begin the shift to managed competition by contracting for collection of smaller waste streams, such as government agency buildings, large nonprofits, street litter baskets, schools, and correctional institutions. In many areas, private carters may be serving customers next door to these DSNY collection points, and in some cases private carters may even be supplementing DSNY service. The City could also solicit bids from the public and private sectors for an expansion of its residential organic waste collection pilot program. While the separation of organic material reduces the fees paid by the City to transport and landfill garbage, the introduction of a new waste stream increases the cost of collection. Reducing the per-ton collection cost through managed competition would help the City contain the added cost of expansions to the program.

These limited efforts should be accompanied or followed by competitive contracting for residential collection in a few existing or modified sanitation districts; eventually, drawing on lessons from experience, the approach should be applied citywide. In the long term, if the City reduces its residential garbage collection costs 20 percent, taxpayers would save $220 million annually.50

The successful implementation of managed competition on a large scale will require time to design application requirements, award criteria, and oversight controls. DSNY staff and private waste carters would also require time to evaluate the cost of providing service, develop comparable unit-cost measures, and prepare bids.

-

Franchises for more efficient commercial waste collection

New York City businesses have been well-served by the more than 250 licensed companies collecting (non-construction) commercial waste under the supervision of the Business Integrity Commission (BIC). Instances of crime and corruption are rare, and prices are reasonable and capped. Despite these benefits, the City’s “open permit” approach for commercial waste collection creates a system in which garbage trucks often cross paths and serve the same blocks. That is inefficient in terms of cost for collection, and it creates unnecessary traffic congestion and greenhouse gas emissions.

To eliminate such overlap, the City should shift from “open” competition to competitively awarded franchises for service in designated districts. The franchise should not be given exclusively to one carter but instead limited to a small number of firms. Such “non-exclusive” franchises allow for greater competition and provide greater opportunity for small- and medium-size businesses to compete. The franchises should be awarded separately for each sanitation district, and the number of awardees should be based on the concentration of businesses in each district. For instance, businesses in midtown Manhattan could choose from five different carters but businesses in a largely residential neighborhood could have a selection of three carters. Maintaining a high number of franchise agreements would help maintain existing competitive forces in the waste industry. The franchise competitions should be staggered and should span a period of at least seven years to enable sufficient capital investment.51 The franchise agreements should include standards for worker safety and vehicle environmental performance. Not surprisingly, with so many private waste carters operating in the city, current environmental performance and labor standards vary greatly.52

DSNY should be permitted to compete for commercial franchises. Particularly in heavily residential areas, DSNY may have an advantage over private carters whose customers are less densely spaced. To be awarded a franchise, DSNY and private carters would have to guarantee specified service levels at a competitive price.

The savings from franchise arrangements for commercial collections would be modest. Assuming 5 percent reductions from the current estimated collection costs, the savings would be $26 million annually.53

-

More diverse snow removal capacity

Any redesign of waste collection practices in New York City needs simultaneously to address its snow removal procedures, which currently rely almost entirely on DSNY employees. Under the current system, the City must consider the impact on snow removal – a service provided infrequently during a limited portion of the year – whenever employment levels for waste collection – a year-round service –are altered. This dependence on sanitation workers creates a great impediment to collection efficiencies, because no alternative is available for the periodic demands for snow removal.

In most large cities, a more diverse group of workers are assigned snow removal responsibilities. Most commonly a combination of public works employees (for example, transportation, parks, water, and sanitation) completes the task, with assistance from private contractors during heavy snowfalls. For example, in Indianapolis, where public employees serve five of 12 garbage districts, the City trains workers engaged full-time in park maintenance, facility maintenance, traffic operations and street maintenance to remove snow.54 To maintain regular trash collections, sanitation workers are only used during severe storms, and private contractors are called in if the snowfall exceeds 6 inches. In Toronto two-thirds of the snow removal budget is for private contractors; one-half of Toronto is served by private garbage collection and the other half is served by public sanitation crews.55

To start, the City could build on a list of pre-authorized private contractors created after the December 2010 blizzard.56 The City pays an annual retainer to be able to call on these contractors during a snow emergency. Private waste carters who operate in the city, and thus have the proper experience and licenses to drive trucks down city streets, may be good candidates for additions to the list. The City should also train a mix of public employees outside DSNY to use plows on city-owned vehicles. Again, the ideal candidates would have a Commercial Driver License (CDL) and experience driving trucks within the city. Other city government positions require CDLs, such as bus drivers at the Transit Authority and construction and maintenance workers across multiple agencies. Another approach is to create a standby pool of qualified retired sanitation drivers to be activated in the event of snow. Since many DSNY employees work for 20 years and retire in middle-age, some retirees may be willing and physically able to participate in snow operations.57

Conclusion

The proper and efficient removal of garbage from New York City’s homes and businesses is essential to the physical and economic health of the city. Current service standards could be maintained at a substantially lower cost and with a smaller environmental footprint.

Progress toward a new solid waste management system should begin with immediate changes in the sanitation workers’ labor contract that reduce barriers to greater efficiency along with necessary accompanying City Council actions. In the longer term the City should use managed competition for residential garbage and franchise agreements for commercial garbage to gain the savings demonstrated elsewhere. City residents should have the financial incentive of a volume-based, pay-as-you-throw fee to generate less waste, and the City’s dependence on DSNY staff for snow removal should be lessened.

The fiscal gains from the proposed measures are summarized in Table 2. A redesigned system following these strategies would yield annual savings of nearly $100 million in the short term and more than $300 million over the long term.

Footnotes

- Citizens Budget Commission, Taxes In, Garbage Out: The Need for Better Solid Waste Disposal Policies in New York City (May 2012), www.cbcny.org/sites/default/files/REPORT_SolidWaste_053312012.pdf.

- Ehren Goossens, "Covanta, New York Sign 20-Year Garbage-to-Energy Contract," Bloomberg News (August 26, 2013), www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-08-26/covanta-new-york-sign-20-year-garbage-to-energy-contract.html; and “Service Contract for Municipal Solid Waste Management Transportation and Disposal (North Shore Marine Transfer Station and East 91st Street Marine Transfer Station) between the City of New York, New York and Covanta 4Recovery, L.P.” (July 3, 2013), www.energyjustice.net/files/incineration/covanta/NYC-Covanta-contract.pdf.

- New York City Department of Environmental Protection, “City Announces Innovative New Partnerships that Will Reduce the Amount of Organic Waste Sent to Landfills, Produce a Reliable Source of Clean Energy and Improve Air Quality” (press release, December 19, 2013), www.nyc.gov/html/dep/html/press_releases/13-121pr.shtml#.U9jxxuNdXHU.

- Citizens Budget Commission, 12 Things New Yorkers Should Know About Their Garbage (May 2014), www.cbcny.org/sites/default/files/REPORT_GarbageFacts_05222014.pdf.

- Some of the 250 licensed private carters are inactive, duplicative or provide one-time garbage removal services.

- New York City and Washington, D.C. data are for fiscal year 2012. Chicago data is for fiscal year 2011, and Dallas and Phoenix data are for fiscal year 2009.

- The short-term recommendations would allow a reduction of 611 sanitation workers. The adopted budget for fiscal year 2015 included funding for 5,901 uniformed sanitation workers. New York City Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Budget for Fiscal Year 2015, Supporting Schedules, p. 3047, www.nyc.gov/html/omb/downloads/pdf/ss6_14.pdf. The average attrition rate for the New York City Employees’ Retirement System (to which sanitation workers belong) from fiscal year 2004 through 2013 was 5.1 percent. Attrition is defined as any withdrawal from active membership, including those due to death and retirement. New York City Employees’ Retirement System, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Years Ended June 30, 2013, and June 30, 2012, p. 213, www.nycers.org/(S(h5dfihacvfkmcrmx0p5vvu45))/Pdf/cafr/2013/CAFR2013.pdf.

- CBC staff analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department of Sanitation.

- If DSNY could alter the frequency of refuse collection and recalibrate the routes to ensure every curbside refuse truck-shift picks up at least 12 tons, the City could reduce the number of two-worker, refuse truck-shifts by 48,286 from 259,327 to 211,040. That would permit a reduction of 466 positions and save $72 million annually. Savings based on the average annual compensation cost of $153,594 per DSNY worker in fiscal year 2012 and an estimated 207 shifts per worker per year after accounting for holidays, vacation, and sick days. CBC staff analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department Sanitation; and New York City Office of Management and Budget, Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2014, Message of the Mayor (May 2, 2013), p. 136, www.nyc.gov/html/omb/downloads/pdf/mm5_13.pdf. Savings from route extensions may be partially offset by increased relays to dump garbage after the collection crews’ shifts.

- Other differential payments include 50 percent extra pay for holidays and 12.5 percent extra pay for Saturdays (50 percent differential for 2 hours). New York City Office of Labor Relations, Sanitation Workers, CBU 49, Executed Contract, 03-02-07 to 09-20-11 (May 2009), p. 4, www.nyc.gov/html/olr/downloads/pdf/collective_bargaining/Sanitation%20Workers,%20CBU%2049,%20Executed%20Contract,%2003-02-07%20to%2009-20-11.pdf.

- CBC staff analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department of Sanitation; and Henningson, Durham & Richardson Architecture and Engineering, P.C. and its Subconsultants, Commercial Waste Management Study, Volume II: Commercial Waste Generation and Projections, prepared for the New York City Department of Sanitation for submission to the New York City Council (March 2004), Appendix C, p. 12, www.nyc.gov/html/dsny/downloads/pdf/swmp/swmp/cwms/cwms-ces/v2-cwgp.pdf.

- CBC staff analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department of Sanitation.

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2012 American Community Survey, Selected Housing Characteristics (accessed September 12, 2014), factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- CBC analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department of Sanitation.

- The City’s new recycling plant in Brooklyn was built to process mixed metal, glass and plastic, but in anticipation of high levels of contamination, its design included technology to sort paper. However, it was not constructed to handle a high volume of commingled recycling. Action Environmental Services, “Action Environmental Group, Inc. announces its launch of an Optical Sorter to improve the way NYC businesses recycle at the NYC GoGreen conference” (press release, September 26, 2013), actionenvironmentalgroup.com/about-iws/news-awards/21-action-environmental-group-inc-announces-its-launch-of-an-optical-sorter-to-improve-the-way-nyc-businesses-recycle-at-the-nyc-gogreen-conference; Nicholas Stango, “A Tour of the Largest Commingled Recycling Plant in the U.S.” Gizmodo (January 3, 2014), gizmodo.com/a-tour-of-the-largest-commingled-recycling-plant-in-the-1493137288; and Megan Workman, “Into the Sunset” Recycling Today (April 2014), vdrs.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/16.MRF-Series-Reprint-proof4.pdf.

- CBC staff analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department of Sanitation.

- Alliance for Downtown New York, “The Downtown Alliance Expands Innovative Solar-Powered Trash Collection by Adding Recycling to Successful High-Tech Waste Collection System” (press release, September 8, 2014), www.downtownny.com/sites/default/files/bigbelly%20expansion.pdf; Emily Ruscoe, “BigBelly Solar-Powered Recycling Bins Headed to Times Square,” Gothamist (March 15, 2013), gothamist.com/2013/03/15/big_belly_recycling_bins_headed_to.php#photo-2; and Wilder Fleming, “Did Sanitation Trash a Cost-Saving Garbage Solution?” The New York World (October 17, 2012), www.thenewyorkworld.com/2012/10/17/garbage-compactors/.

- “BigBelly” containers require higher upfront investments – about $3,000 per container, versus $124 for the typical DSNY basket – and ongoing service fees for data monitoring. Cost data provided by the New York City Department of Sanitation.

- Gordon Feller, “Dutch Successes,” Waste Management World, vol. 11, issue 1 (January 1, 2010), www.waste-management-world.com/articles/print/volume-11/issue-1/features/dutch-successes.html; and Vesela Todorova, “Dubai’s Neat Streets as Rubbish is Swept Under the Concrete,” The National (June 22, 2012), www.thenational.ae/news/uae-news/environment/dubais-neat-streets-as-rubbish-is-swept-under-the-concrete.

- "A Geek’s Tour of Barcelona,” Decoding the New Economy (November 1, 2013), paulwallbank.com/2013/11/01/touring-barcelona-smart-city-internet-of-things/.

- In fiscal year 2013, sanitation workers collected an average of 9.9 tons of refuse per truck-shift. City of New York, Mayor's Management Report, Fiscal Year 2013 (September 2013), p. 56, www.nyc.gov/html/ops/downloads/pdf/mmr2013/2013_mmr.pdf.

- CBC staff analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department of Sanitation.

- New York City Mayor’s Office of Operations, Mayor’s Management Report, Additional Tables, Fiscal Year 2013 (September 2013), p. 19, www.nyc.gov/html/ops/downloads/pdf/mmr2013/full_report_addtional_tables_2013.pdf.

- CBC staff analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department of Sanitation.

- Savings calculation assumes aforementioned flexibility measures are implemented first and allow DSNY to increase the average amount of refuse collected per truck-shift from 10 to 12 tons. Average collection hours per ton for “Roll-on/Roll-off” refuse collection trucks was 0.38 in fiscal year 2012, and if average refuse collected per truck-shift increased to 12 tons, average collection hours per ton for curbside refuse collection would be 1.31. If DSNY were able to containerize another 10 percent of curbside refuse, or 258,698 tons, the number of labor hours required to collect refuse would drop by 240,614. This reduction would eliminate 145 positions (from 204 to 59), based on 8-hour shifts and an estimated 207 shifts per worker per year after accounting for holidays, vacation, and sick days. Based on the average annual compensation cost of $153,594 per DSNY worker in fiscal year 2012, the change would save $22 million. A bonus payment of $193 would cost $2 million (59 workers * 207 shifts * $193). CBC staff analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department Sanitation; and New York City Office of Management and Budget, Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2014, Message of the Mayor (May 2, 2013), p. 136, www.nyc.gov/html/omb/downloads/pdf/mm5_13.pdf. While automated trucks are more expensive than DSNY’s rear-loading collection trucks, fewer trucks would need to be purchased.

- In fiscal year 2012, DSNY paid $2.6 million for dump-on-shift differentials. Data provided by the New York City Office of Management and Budget. Assuming all workers received the productivity bonus, an estimated $1.7 million was paid in fiscal year 2012 for meeting tons per truck-shift targets (358,437 curbside truck-shifts * $2.41 *2). CBC staff analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department Sanitation.

- For a list of cities with PAYT fees, see: Mecklenburg County Land Use & Environmental Services Agency, Solid Waste Division, Best Practices for Local Government Solid Waste Recycling, Diversion from Landfill and Waste Reduction (December 2011), p. 3, charmeck.org/mecklenburg/county/SolidWaste/ManagementPlan/Documents/BestPracticesRecyclingStudy.pdf.

- Recology, Sunset Scavenger Golden Gate, “Residential Rates” (accessed September 12, 2014), www.recologysf.com/index.php/for-homes/residential-rates#residential-rates.

- Recology, Sunset Scavenger Golden Gate, “Lifeline Rates” (accessed September 12, 2014), www.recologysf.com/index.php/for-homes/residential-rates#lifeline-rates; and City and County of San Francisco Department of Public Works, “Residential and Apartment Refuse Rates, Effective July 1, 2014” (accessed September 12, 2014), www.sfdpw.org/modules/showdocument.aspx?documentid=4244.

- Recology, Sunset Scavenger Golden Gate, “Apartment Rates” (accessed September 12, 2014), www.recologysf.com/index.php/for-homes/apartment-rates; and City and County of San Francisco Department of Public Works, “Residential and Apartment Refuse Rates, Effective July 1, 2014” (accessed September 12, 2014), www.sfdpw.org/modules/showdocument.aspx?documentid=4244.

- Berliner Stadtreinigungsbetriebe (BSR), “The BSR Rates 2013/2014” (in German), www.bsr.de/assets/downloads/Tarife_2013_2014_Uebersicht_web.pdf; and Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment, “Municipal Waste Management in Berlin” (December 2013), www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/umwelt/abfallwirtschaft/downloads/siedlungsabfall/Abfall_Broschuere_engl.pdf.

- Currency conversion based on currency rates as of September 12, 2014.

- Berliner Stadtreinigungsbetriebe (BSR), “Hausmüll: BSR-Müllsäcke” (in German, accessed September 12, 2014), www.bsr.de/9867.html.

- Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment, “Municipal Waste Management in Berlin” (December 2013), p. 25, www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/umwelt/abfallwirtschaft/downloads/siedlungsabfall/Abfall_Broschuere_engl.pdf.

- City of Zurich, City Engineering and Waste Department, “Disposal and Recycling” (in German, accessed September 12, 2014), www.stadt-zuerich.ch/content/ted/de/index/entsorgung_recycling/sauberes_zuerich/entsorgen_wiederverwerten/hauskehricht/hauskehricht_preise.html#contenttabs. Currency conversion based on currency rates as of September 12, 2014.

- An annual organics subscription costs only 130 Swiss Francs ($139) for the first two years. City of Zurich, City Engineering and Waste Department, “Biowaste Services and Prices” (in German, accessed September 12, 2014), www.stadt-zuerich.ch/content/dam/stzh/ted/Deutsch/erz/Sauberes_Zuerich/Formulare_und_Merkblaetter/SZ_Bioabfall_DL_Preise_1402.pdf. Currency conversion based on currency rates as of September 12, 2014.

- Seoul Global Center, “Living: Garbage Disposal” (accessed September 12, 2014), global.seoul.go.kr. Currency conversion based on currency rates as of September 12, 2014.

- Catherine Bosley and Carolyn Bandel, “Wrong Garbage Bag? Swiss Trash Police are on the Case,” Bloomberg News (June 5, 2014), www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-06-04/swiss-garbage-police-irk-foreigners-reeling-after-vote.html.

- City of Toronto, “2014 Solid Waste Rates and Fees” (accessed September 12, 2014), www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=b16687fc1b273410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD&vgnextchannel=03ec433112b02410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD; and City of Toronto Municipal Code, Chapter 844, Article VII, Section 28-32 (accessed September 12, 2014), www.toronto.ca/legdocs/municode/1184_844.pdf.

- Currency conversion based on currency rates as of September 12, 2014.

- New York City Council, Int. 1157-2013 and Int. 1135-2013, legistar.council.nyc.gov/Legislation.aspx.

- Lisa A. Skumatz and David J. Freeman, Pay as You Throw (PAYT) in the US: 2006 Update and Analyses (submitted by Skumatz Economic Research Associates to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Solid Waste, December 30, 2006), p. 7, www.epa.gov/osw/conserve/tools/payt/pdf/sera06.pdf.

- If PAYT reduced the generation of New York City curbside household refuse by 6 percent, the number of tons collected by DSNY would fall by 155,219, which would reduce the number of annual truck-shifts by 15,522. Based on the average annual compensation cost of $153,594 per DSNY worker in fiscal year 2012 and an estimated 207 shifts per worker per year after accounting for holidays, vacation, and sick days, each shift assignment costs the department approximately $742. Because curbside shifts require two workers, one truck-shift costs an average of $1,484. Based on these costs, that change would reduce collection costs by $23 million. DSNY would save an additional $14 million from avoiding the export of these tons. If another 11 percent of curbside household refuse was diverted from refuse to the recycling bin, the City would increase diversion by 284,568 tons and save the difference between garbage export fees and recycling fees/revenues, or $19 million. In fiscal year 2012, average refuse export costs were $92 per ton; average metal, glass and plastic processing fees were $72.58 per ton; and average paper revenues were $11.50 per ton. Calculation assumes that 57 percent of the newly recycled material is paper and 43 percent is metal, glass, and plastic, the same proportion as current curbside collections. Additional savings would likely follow from reductions in equipment and fuel costs. CBC staff analysis of fiscal year 2012 collection data provided by the New York City Department Sanitation; New York City Office of Management and Budget, Export Costs by Vendor, Fiscal Year 2012; and New York City Office of Management and Budget, Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2014, Message of the Mayor (May 2, 2013), pp. 136-7, www.nyc.gov/html/omb/downloads/pdf/mm5_13.pdf. Savings from PAYT would be partially offset by initial implementation costs and ongoing administrative costs.

- Geoffrey F. Sigal, Adam B. Summers, Leonard C. Gilroy, AICP and W. Erik Bruvold, Streamlining San Diego: Achieving Taxpayer Savings and Government Reforms Through Managed Competition (September 2007), San Diego Institute for Policy Research and Reason Foundation, www.policyarchive.org/handle/10207/bitstreams/5920.pdf; Benjamin Dachis, C.D. Howe Institute, Picking Up Savings: The Benefits of Competition in Municipal Waste Services, Commentary, No. 308 (September 2010), p.11, www.cdhowe.org/pdf/commentary_308.pdf; National Solid Waste Management Association, Privatization: Saving Money, Maximizing Efficiency and Achieving Other Benefits in Solid Waste Collection, Disposal and Recycling (April 2012), www.environmentalistseveryday.org/docs/research-bulletin/Research-Bulletin-Privatization.pdf; and Benjamin Dachis, “In Garbage Collection, Competition is Rarely Wasted,” The Globe and Mail (February 11, 2011), www.theglobeandmail.com/commentary/in-garbage-collection-competition-is-rarely-wasted/article565860/.

- Savas, E.S. Privatization in the City: Successes, Failures, Lessons. (CQ Press, 2005); Geoffrey F. Sigal, Adam B. Summers, Leonard C. Gilroy, AICP and W. Erik Bruvold, Streamlining San Diego: Achieving Taxpayer Savings and Government Reforms Through Managed Competition, San Diego Institute for Policy Research and Reason Foundation (September 2007), www.policyarchive.org/handle/10207/bitstreams/5920.pdf; Ryan Holeywell, Public Workers Bid for Their Jobs, Governing (October 2012), www.governing.com/topics/public-workforce/gov-public-workers-bid-for-jobs.html; and City of Charlotte Procurement Services Division, City of Charlotte Managed Competition Program (April 2002), charmeck.org/city/charlotte/SharedServices/Procurement/Documents/Older%20Documents/GeneralInformationAboutManagedCompetitionInCharlotte.pdf.

- City of Chicago, 2014 Annual Financial Analysis, p. 20, www.cityofchicago.org/content/dam/city/depts/obm/supp_info/2015Budget/AFA_2014_Final_web.pdf. Also see: City of Chicago, “Mayor Rahm Emanuel Announces Citywide Recycling in 2013” (press release, April 5, 2012), www.cityofchicago.org/city/en/depts/mayor/press_room/press_releases/2012/april_2012/mayor_rahm_emanuelannouncescitywiderecyclingin2013.html. The Chicago Federation of Labor has reported the City’s savings estimates do not include lost revenue from the sale of recyclables. Chicago Federation of Labor, City of Chicago 2012 Budget Efficiency Report (July 26, 2011), pp. 8-10, www.chicagolabor.org/news/press-releases/body/Efficiencyreport.pdf.

- The Civic Federation, Managed Competition (September 11, 2013), pp. 23-25, www.civicfed.org/sites/default/files/Managed%20Competition%20Issue%20Brief.pdf.

- City of Chicago, 2014 Annual Financial Analysis, p. 20, www.cityofchicago.org/content/dam/city/depts/obm/supp_info/2015Budget/AFA_2014_Final_web.pdf.

- Frontier Centre for Public Policy, Managed Competition: The Phoenix Experience (October 1, 2000), old.fcpp.org/publication.php/245; San Diego Business Office, Managed Competition Pre-Competition Assessment Report, Environmental Services Department: Solid Waste Collection and Support Services (September 27, 2012), pp. 20-21, www.sandiego.gov/business/mc/pdf/pca/swcreport120927.pdf; Hilton Collins, “Governments Save Money Using Managed Competition,” Government Technology (January 17, 2011), www.govtech.com/transportation/Governments-Save-Money-Using-Managed-Competition.html?page=1; Katherine Barrett and Richard Greene, “Public v. Private Employees: Who Wins in a Bidding War?” Governing (November 2012), www.governing.com/columns/smart-mgmt/col-public-private-employees-who-wins.html; and “The City of Charlotte, NC Solid Waste Services Department: Reorganizing for Success,” Waste Advantage Magazine (February 2011), pp.14-19 wasteadvantagemag.com/2011-issues/.

- Savings based on total collection costs in fiscal year 2012 of $1,122 million, minus collection savings of $23 million from implementing pay-as-you-throw fees. CBC staff analysis of New York City Department of Sanitation, Bureau of Planning and Budget, Cost per Ton Analysis, Fiscal Year 2012. For full explanation of savings from pay-as-you-throw fees, see endnote 43.

- The typical sanitation truck has a lifespan of seven years. Current BIC regulations limit contracts to two years, stifling capital investment. Following the example of other cities, certain types of special waste (for example, medical, hazardous, and construction) should be excluded from the franchise agreements. These types of waste are typically picked up by specialty carters; other firms would not be equipped to handle these waste streams.

- For non-construction and demolition carters, 17 percent of private garbage trucks are more than 23 years old, and 73 percent are more than 10 years old. The average age of these trucks is 15.6 years; in contrast the average age of a DSNY heavy-duty vehicle is only 65 months. New York City Business Integrity Commission and the Environmental Defense Fund, New York City Commercial Refuse Truck Age-Out Analysis, Prepared by M.J. Bradley & Associates (September 2013), pp. 7-8, www.edf.org/sites/default/files/EDF-BIC%20Refuse%20Truck%20Analysis%20092713.pdf; and New York City Mayor’s Office of Operations, Mayor’s Management Report, Fiscal Year 2013, Additional Tables (September 2013), p. 33, www.nyc.gov/html/ops/downloads/pdf/mmr2013/full_report_addtional_tables_2013.pdf. Also see: Alliance for a Greater New York (ALIGN), Transform Don’t Trash NYC (September 2013), www.alignny.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/TransformDontTrashNYCReport_FINAL_Lo.pdf.

- Based on average price per ton for collection and disposal of $184.69 in 2012, as reported to the New York City Business Integrity Commission, and estimated commercial collection costs of $526 million. Private sector collection costs are estimated as total cost minus disposal costs. Disposal costs are estimated based on the distribution of waste among recyclables (paper, cardboard, combined plastic, metal, and glass) and other material that is landfilled. The distribution is based on urban, commercial areas in New York in 2010, as reported in New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, “Solid Waste Composition and Characterization, MSW Materials Composition in New York State” (2010), Detailed Composition Analysis Table, www.dec.ny.gov/chemical/65541.html. Disposal cost calculation assumes the following: 1) 14 percent of commercial waste is cardboard; 14 percent is paper; 24 percent is metal, glass, or plastic; and 49 percent is refuse; 2) 80 percent of recyclable material is appropriately recycled and the remainder is sent to landfill; 3) Carters receive $100 per ton of cardboard and $25 per ton of paper and pay recycling processers $72.58 per ton; and 4) Carters pay $88 per ton of refuse, based on the fees at non-rail waste transfer stations used by DSNY in fiscal year 2011.

- Email communication with Lesley Gordon, Public Information Officer of the Indianapolis Department of Public Works, September 17, 2013. Also see: City of Indianapolis, Department of Public Works, “Snow Division” and “Solid Waste Districts” (accessed July 31, 2014), www.indy.gov/eGov/City/DPW/Snow/Pages/SnowHome.aspx and www.indy.gov/eGov/City/DPW/Trash/Pages/SolidWasteDistricts.aspx.

- City of Toronto Transportation Services, “Confirmation of Levels of Service for Roadway and Roadside Winter Maintenance Services” (October 28, 2013), p. 3, www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/pw/bgrd/backgroundfile-63459.pdf.

- The Council of the City of New York, Report of the Infrastructure Division and Committee on Sanitation and Solid Waste Management, Oversight: Private Contracts and Snow Management (June 27, 2013), legistar.council.nyc.gov/View.ashx?M=F&ID=2556664&GUID=42CF9AE1-23D6-455B-883D-3E4C8AFDB550.

- New York State law limits public-sector earnings for retired public employees to $30,000 annually. Laws of New York State, Retirement and Social Security Law, Article 7, Section 212, public.leginfo.state.ny.us/menugetf.cgi?COMMONQUERY=LAWS.