Medicaid Supplemental Payments

State Workgroup Makes Limited Progress on Part of the Problem

New York State’s $78 billion Medicaid program includes $5.3 billion of “supplemental payments;” that is, payments not directly associated with provision of medical services. These supplemental payments are crucial to the financial viability of many hospitals across the state, especially those largely serving uninsured and Medicaid populations.

The supplemental payments are facing policy challenges at the federal and state levels. First, if implementation of current federal law proceeds, the supplemental payments would be reduced significantly. New York State would face a $2.9 billion annual cut that will be phased in beginning October 1, 2019. Second, the State’s method for distributing a $1 billion portion of the supplemental payments has been heavily criticized in recent years on grounds that the funds are not well targeted to hospitals with the greatest financial need.

These pressures led the State to convene a workgroup to consider changes to the supplemental payment pool. The Indigent Care Workgroup conducted a review of the current framework and formulas for supplemental payments; three of its members representing important constituencies suggested alternative distribution strategies and formulas; and the group identified multiple criteria for assessing any new distribution methods. This month the workgroup released a report summarizing its work, but did not make specific recommendations for how to address the current challenges.

The report will help inform stakeholders and elected officials, but it remains up to the State’s legislative and executive leaders to identify specific actions that will remedy the inequities in current distribution methods and adjust to looming federal cuts.

Background on the $5.3 billion Supplemental Payments

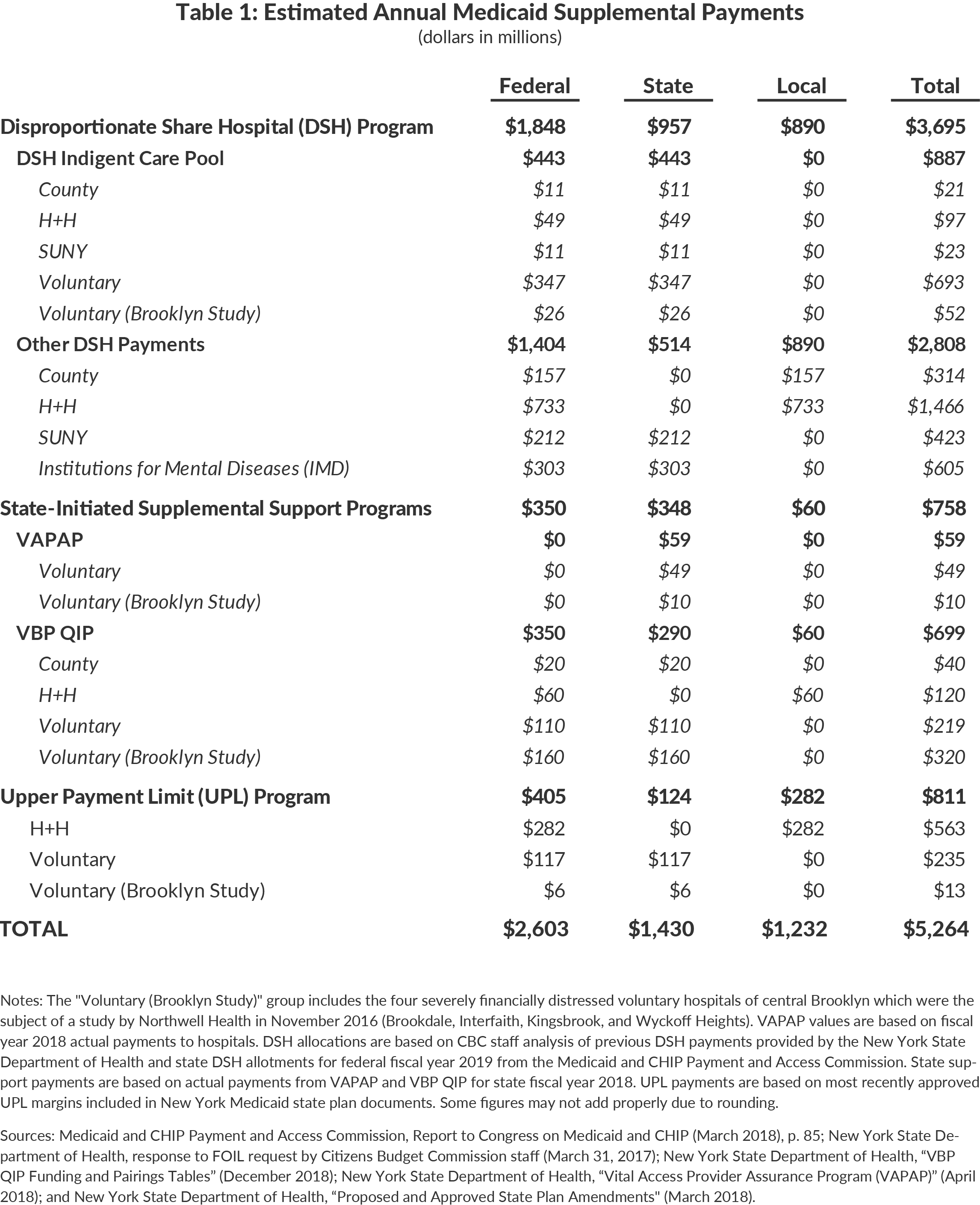

The three main types of Medicaid supplemental payments are:

- Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Program ($3.7 billion);

- Upper Payment Limit (UPL) Program ($811 million); and

- State-Initiated Supplemental Support Programs ($758 million).

Each of these programs has different financing sources and distribution methods. These payments are summarized in Table 1.

Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Program

DSH is a federal program that provides a set annual allotment to be distributed to hospitals to make up for financial shortfalls due to serving uninsured and Medicaid patients. The federal funding–over $1.8 billion in New York–must be matched with state or local funding, yielding $3.7 billion in total funding to distribute.

States have considerable discretion over how to distribute the DSH funds to hospitals. New York divides the DSH funding into two pools, one known as the Indigent Care Pool ($1.1 billion) and another for public hospitals ($2.6 billion).1 The Indigent Care Pool derives its nonfederal funding from State taxes including taxes on hospital revenues. The Indigent Care Pool provides a base payment to 175 hospitals (nearly every hospital in the state) and additional support based on a complex formula. The Indigent Care Pool has been the subject of critical review recently, with multiple analyses concluding it directs too much money to relatively financially healthy hospitals.2

The remaining $2.6 billion is distributed to the State’s public hospitals. The nonfederal portion of the funding is from State taxes for payments to State hospitals and from local (county or city) funds for payments to local public hospitals including those of New York City’s Health + Hospitals. The $2.6 billion is distributed based on the financial losses each hospital experiences from uninsured and Medicaid financial shortfalls. Federal law limits the amount available to State hospitals for mental diseases.

Upper Payment Limit (UPL) Program

UPL is a federally-authorized program that provides payments to hospitals to supplement revenue from Medicaid patients so that it is comparable to that for Medicare patients. UPL payments to individual hospitals are calculated by the State with federal oversight and limits are set for individual hospitals.

In New York, voluntary hospitals receive $235 million through UPL payments, with the nonfederal portion derived from State revenues.3 The UPL amount received by voluntary hospitals is credited against their Indigent Care Pool allotments, with the combined total set at $995 million each year.

Public hospitals of New York City Health + Hospitals (H+H) also receive UPL funding. In the most recent audited year H+H hospitals received $563 million. New York City finances the nonfederal half of these payments.

State-Initiated Supplemental Support Programs

During 2015 the State created two programs–the Vital Accessed Provider Assurance Program (VAPAP) and the Value Based Payment Quality Improvement Program (VBP QIP)–to provide additional support to financially distressed hospitals. VBP QIP is the larger program, directing $350 million in state and local funds and $350 million in matching federal funds to 22 hospitals in severe financial distress. The funding amounts for VBP QIP are set prior to the beginning of each year based on estimated need. A significant share of this funding–approximately $330 million annually–is directed to four hospitals in Brooklyn.4 VAPAP resources are available on a more ad hoc basis. VAPAP is funded only with state funds and can be directed on short notice to hospitals with immediate cash flow needs. Annually approximately $59 million in VAPAP funding is distributed to 12 hospitals.

Persistent Issues and the Indigent Care Workgroup

Two central problems plague the supplemental payment pool in New York.

Federal Cuts to DSH

New York receives the largest allocation of DSH funding among the states, but will also receive the largest funding cuts when reductions enacted with the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are implemented. The ACA included cuts to DSH since it was intended to reduce the number of uninsured Americans (and therefore financial losses associated with serving the uninsured). The cuts–which were initially set to go into effect in federal fiscal year 2013–have been delayed on four occasions. With each delay, however, the cuts have been made deeper.5 (See Table 2.) Under the current federal cut schedule adopted in February 2018, New York will sustain a one-year reduction of $1.4 billion beginning on October 1, 2019 and a cut of $2.9 billion in each of the following five years.6

The state’s current method for distributing DSH funds includes no mechanisms for accommodating these cuts. Because of the hierarchy within the State’s current DSH allocation method, New York City Health + Hospitals would sustain almost all the cuts if the federal reductions are implemented.7 The State’s failure to prepare for cuts created cash flow problems at some public hospitals in October 2017, and those issues will emerge again in October 2019 unless a plan is designed to accommodate the cuts.8 It is possible that Congress will delay or reduce the cuts for a fifth time, an action supported by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). However, MACPAC also recommended changing the method for allocating DSH cuts, which would result in New York’s DSH cut increasing to over $3 billion at full implementation.9

Problematic Allocation of Indigent Care Pool Funds

The $1.1 billion Indigent Care Pool is divided among 175 hospitals, with annual payments ranging from as little as $5,000 to as much as $84 million.10 The current distribution method was established in 2013. Each hospital’s allotment is based on its share of inpatient and outpatient volume for Medicaid and uninsured patients, but adjustments are made including floors and ceilings which prevent a hospital from experiencing large year-to-year shifts in funding.11 As previously noted, the current allocation formula has been criticized as complex and resulting in inequities with some relatively financially healthy institutions receiving large payments. These critiques make a strong case for the need for reform.

Following the fourth delay of the federal DSH cuts and the critical analyses of the Indigent Care Pool, the State convened the Indigent Care Workgroup.12 The Workgroup met four times during 2018 to review the current allocation method and reviewed multiple proposals for changing the formula. A report from the group with background information and suggested criteria for assessing future reforms was recently released, but the Workgroup did not endorse any single proposal or component of a proposal.13

Priorities for Reform

The Workgroup’s report is a significant contribution to the policy deliberations; it is now up to New York’s legislative and executive leaders to respond to the current and looming challenges.14 Two aspects of DSH reform deserve attention this year:

- Establish a more equitable policy for absorbing any future federal DSH cut. Under existing law the full amount of scheduled cuts would first be assessed against payments to New York City Health +Hospitals, reducing its allotment by a total of $4 billion and exacerbating fiscal strains on the system.15 The State should create a plan for mitigating and equitably distributing scheduled federal DSH cuts in advance of their implementation.

- Establish a more equitable distribution policy for the full set of supplemental programs. Any reforms to the Indigent Care Pool, which are just one-sixth of all supplemental payments, should be a part of a consideration of the full menu of supplemental payment programs. New allocation methods and contingency plans for federal cuts should take into account the role and magnitude of all of the supplemental payments and the interactions among them. The source of the nonfederal share of payments should also be reconsidered. The Governor's amended fiscal year 2020 budget, released a week after the Workgroup report, partially addresses these issues by reducing and better targeting a portion of the funding and may provide a basis for broader refom in the enacted budget.

Footnotes

- The payments to public hospitals are made via the Indigent Care Adjustment ($412 million) and additional intergovernmental transfers ($2.2 billion).

- See: Bill Hammond, Hooked on HCRA: New York’s 20-Year Health Tax Habit (Empire Center for Public Policy, January 2017), www.empirecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/HookedOnHCRA-1.pdf; Roosa Tikkanen, Funding Charity Care in New York: An Examination of Indigent Care Pool Allocations (New York State Health Foundation, March 2017), http://nyshealthfoundation.org/uploads/resources/examination-of-indigent-care-pool-allocation-march-2017.pdf; and Carrie Tracy, Elisabeth Benjamin, and Amanda Dunker, Unintended Consequences: How New York State Patients and Safety-net Hospitals are Shortchanged (Community Service Society, January 2018), http://lghttp.58547.nexcesscdn.net/803F44A/images/nycss/images/uploads/pubs/hospital_report_-_final_1_22_18_web.pdf

- Voluntary hospitals may receive up to $339 million annually through UPL. See Section 2807-k of the Public Health Law.

- These four hospitals in Central Brooklyn were the subject of a study conducted by Northwell Health in November 2016 to evaluate the financial condition of the hospitals and to outline possible solutions for redesigning health care delivery in the area, for which the State authorized up to $700 million in capital grant funding. See Northwell Health, The Brooklyn Study: Reshaping the Future of Healthcare (November 2016), www.northwell.edu/sites/northwell.edu/files/d7/20830-Brooklyn-Healthcare-Transformation-Study_0.pdf.

- See: Patrick Orecki, DSH Cuts Delayed: Opportunity for State Reform (Citizens Budget Commission, April 2018) https://cbcny.org/research/dsh-cuts-delayed.

- Estimated reductions are based on a projected gross reduction of $1.448 billion in federal fiscal year 2020 as projected by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). See: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (March 2018), p. 88, www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP-March-2018.pdf. This estimate is approximately proportional to the methodology promulgated in the Federal Register for planned cuts in federal fiscal year 2018. Under the regulation, New York would have received a cut worth approximately one-sixth of the nationwide cut. See: Medicaid Program: State Disproportionate Share Hospital Allotment Reductions, 82 Fed. Reg. 35155 (June 28, 2017).

- For further explanation of the DSH hierarchy and other supplemental payments see: Patrick Orecki, Medicaid Supplemental Payments: The Alphabet Soup of Programs Sustaining Ailing Hospitals Faces Risks and Needs Reform (Citizens Budget Commission, August 2017), https://cbcny.org/research/medicaid-supplemental-payments.

- NYC Health + Hospitals, Letter to Howard Zucker (September 29,2017), www.politico.com/states/f/?id=0000015e-cdf6-ddab-a57f-cff6acde0000; Dan Goldberg, “Outgoing Health + Hospitals chief: Cuomo withholding $380 million from city hospitals,” Politico New York (September 29, 2017), www.politico.com/states/new-york/albany/story/2017/09/29/outgoing-hhc-chief-cuomo-withholding-380-million-from-city-hospitals-114790; and Dan Goldberg and Nick Niedzwiadek, “Cuomo will give Health + Hospitals most of the DSH dollars it requested,” Politico New York (October 13, 2017), www.politico.com/states/new-york/albany/story/2017/10/13/cuomo-will-give-health-hospitals-most-of-the-dsh-dollars-it-requested-115060.

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, DSH Allotment Reductions: Proposed Recommendations (December 13, 2018), p. 17, www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/DSH-Allotment-Reductions-Proposed-Recommendations.pdf.

- Based on CBC staff analysis of data from New York State Department of Health, email to Citizens Budget Commission staff (March 31, 2017).

- See: Section 2807-k of the Public Health Law and 10 NYCRR 86-1.47.

- New York State Department of Health, “New York State Department of Health Announces Indigent Care Workgroup” (June 1, 2018), www.health.ny.gov/press/releases/2018/2018-06-01_indigent_care_workgroup.htm.

- New York State Department of Health, NYS Indigent Care Pool (ICP) Workgroup Report (February 2019), www.health.ny.gov/press/reports/docs/2019_icp_workgroup_report.pdf.

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services would also need to approve the any reforms to DSH allocations, which are part of the State’s Medicaid State Plan. See: New York State Department of Health, New York State Medicaid State Plan (April 2016), www.hcrapools.org/medicaid_state_plan/DOH_PDF_PROD/nys_medicaid_state_plan.pdf.

- See: Mariana Alexander, Lessons from La La Land (Citizens Budget Commission, January 8, 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/lessons-la-la-land.