NYC FY2021 Adopted Budget

Short-Term Balance, Long-Term Challenge

Introduction

After tense negotiations and a close vote ending early morning July 1, the City adopted an $88.2 billion budget for fiscal year 2021. The quick and severe economic disruption opened up large budget gaps in fiscal years 2020 and 2021, over half of which closed with reserves and federal aid. The approach was centered on achieving short-term budget balance amidst quickly evolving circumstances; however, long-term challenges and significant uncertainty—with the risk almost all on the downside—remain.

The Coronavirus Pandemic and Recession Opened up Large Budget Gaps

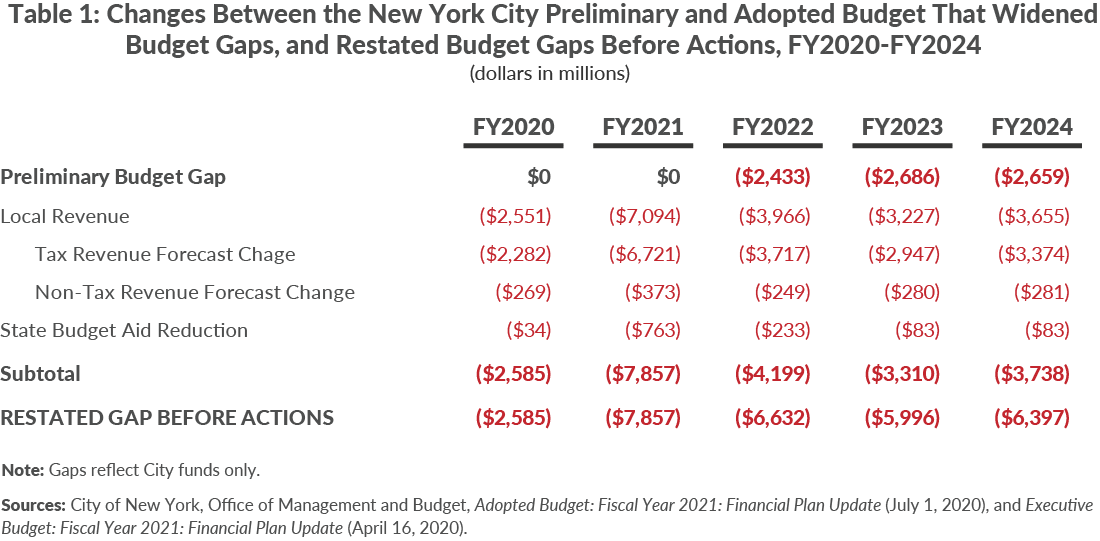

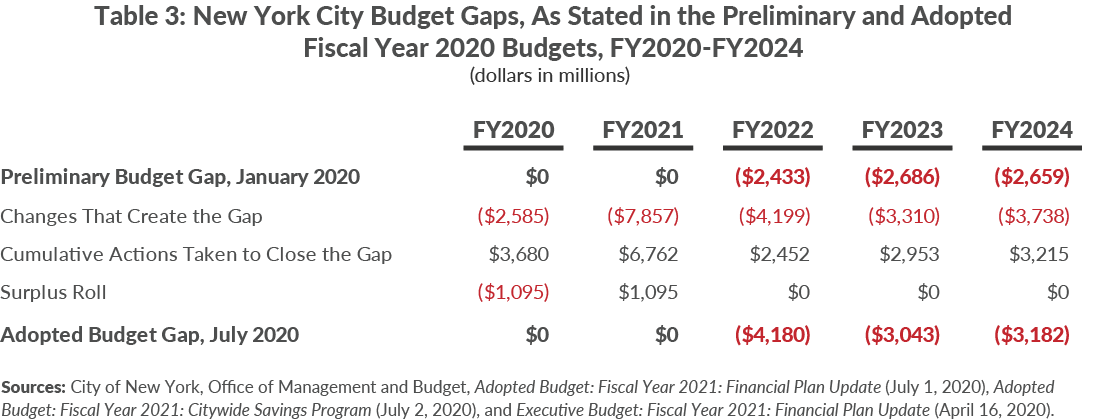

In January 2020 Mayor Bill de Blasio presented a preliminary budget and financial plan that was balanced in fiscal years 2020 and 2021 and had modest gaps of $2.4 billion, $2.7 billion, and $2.7 billion in fiscal years 2022 to 2024, respectively. Between January and June 2020 the pandemic-triggered recession depressed tax and non-tax revenue for both the State and the City. In response, State leaders adopted a budget that reduced aid to New York City and other localities. The tax revenue shortfall and decrease in state aid opened a $10.4 billion budget gap in fiscal years 2020 and 2021, and increased annual budget gaps to at least $6 billion annually starting in fiscal year 2022. (See Table 1.)

Tax Revenues

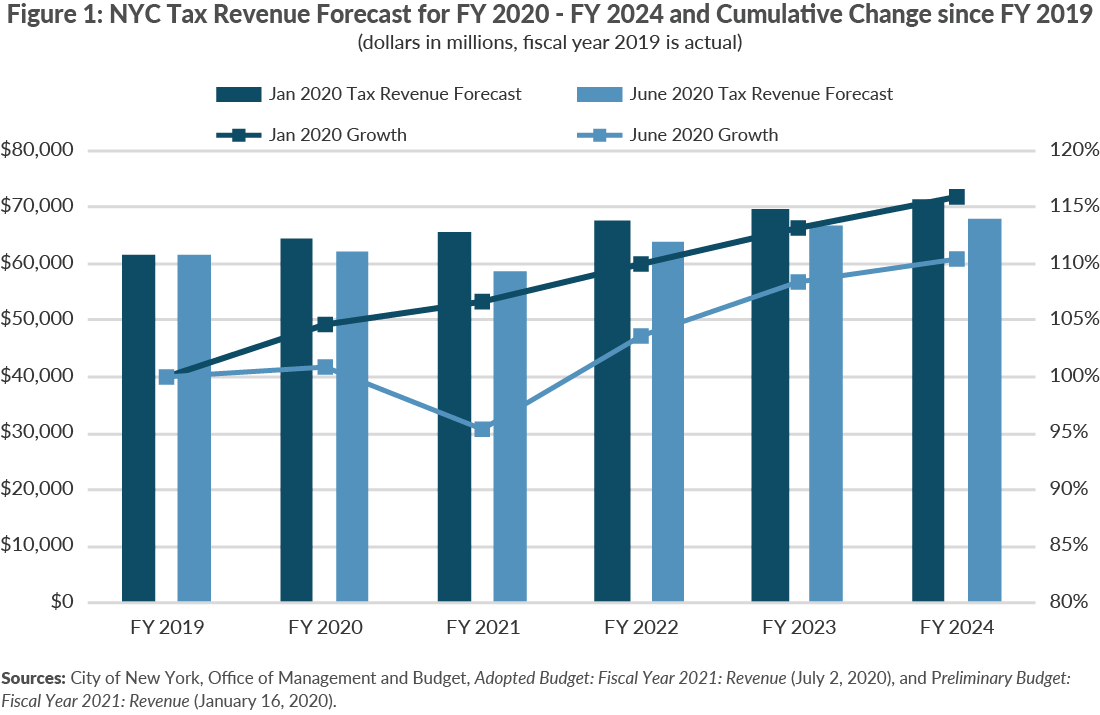

Tax revenues suffered a sudden and deep decline against the January forecast, which projected growth averaging 2.6 percent annually, from $64.4 billion in fiscal year 2020 to $71.3 billion in fiscal year 2024. (See Figure 1.)

In April, May, and June, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) revised this forecast to reflect actual tax collections and evolving economic projections. Projections of fiscal year 2020 and 2021 tax collections were reduced by $9.0 billion, and outyear decreases ranged between $2.9 billion and $3.7 billion in fiscal years 2022 to 2024. Nearly half of the shortfall in fiscal year 2020 is attributed to a drop in sales tax revenue, along with declines in personal income, business income and transaction taxes. These taxes also account for 87 percent of the shortfall in fiscal year 2021.1

Fiscal year 2020 tax collections were flat and are projected to decline 5.5 percent in fiscal year 2021. The recovery is expected to be strong beginning in fiscal year 2022; nevertheless, fiscal year 2024 tax revenues are now forecasted to be 4.7 percent less than in January.

Non-Tax Revenues

The City annually collects about $5 billion in revenues from fees, fines, permits, licenses, and other non-tax sources. The Adopted Budget’s non-tax revenue forecast net reduction was $300 million annually on average.2

State Aid

The Enacted State Budget provides less State aid than the City expected to receive. There was a small decrease of $34 million in fiscal year 2020; however, in fiscal year 2021, the City estimates a $763 million shortfall, including $360 million in education aid, $250 million in intercepted sales tax revenue, $63 million for Metropolitan Transportation Authority paratransit costs, and $90 million in social service cuts.3 In fiscal year 2022 the State will intercept another $150 million in sales tax revenue and reduce social service funding by $83 million.

Over Half of the FY2020 and FY2021 Gaps Were Closed with Reserves and Federal Aid

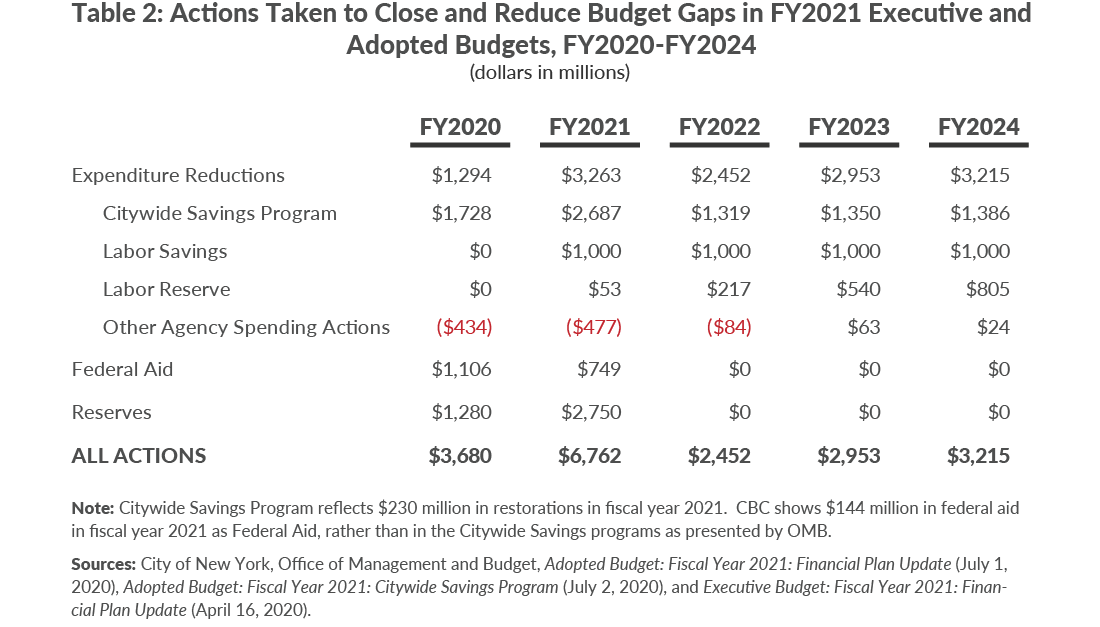

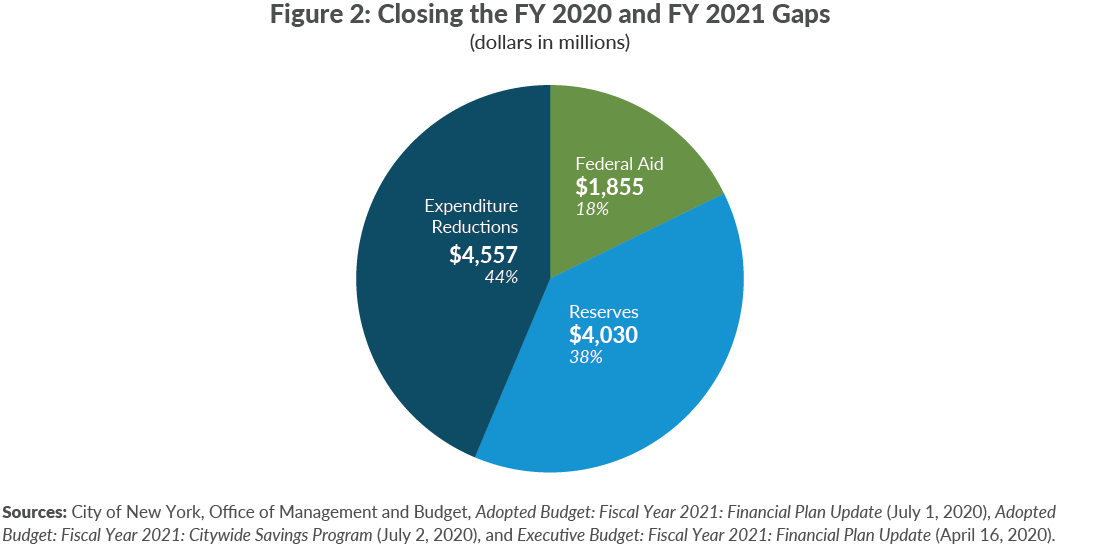

The Executive and Adopted Budgets closed the gaps in fiscal years 2020 and 2021 and narrowed the outyear gaps by reducing planned expenditures, drawing down reserves, and relying on federal aid. (See Table 2.) Less than half of the fiscal year 2020 and 2021 gaps were closed by expenditure reductions (44 percent), with reserves used to close 38 percent and federal aid the remaining 18 percent. (See Figure 2.) Use of reserves during the pandemic and recession are appropriate; however, as reserves are non-recurring, the City will need to find other expenditure reductions or resources to fill outyear gaps.

Expenditure Reductions

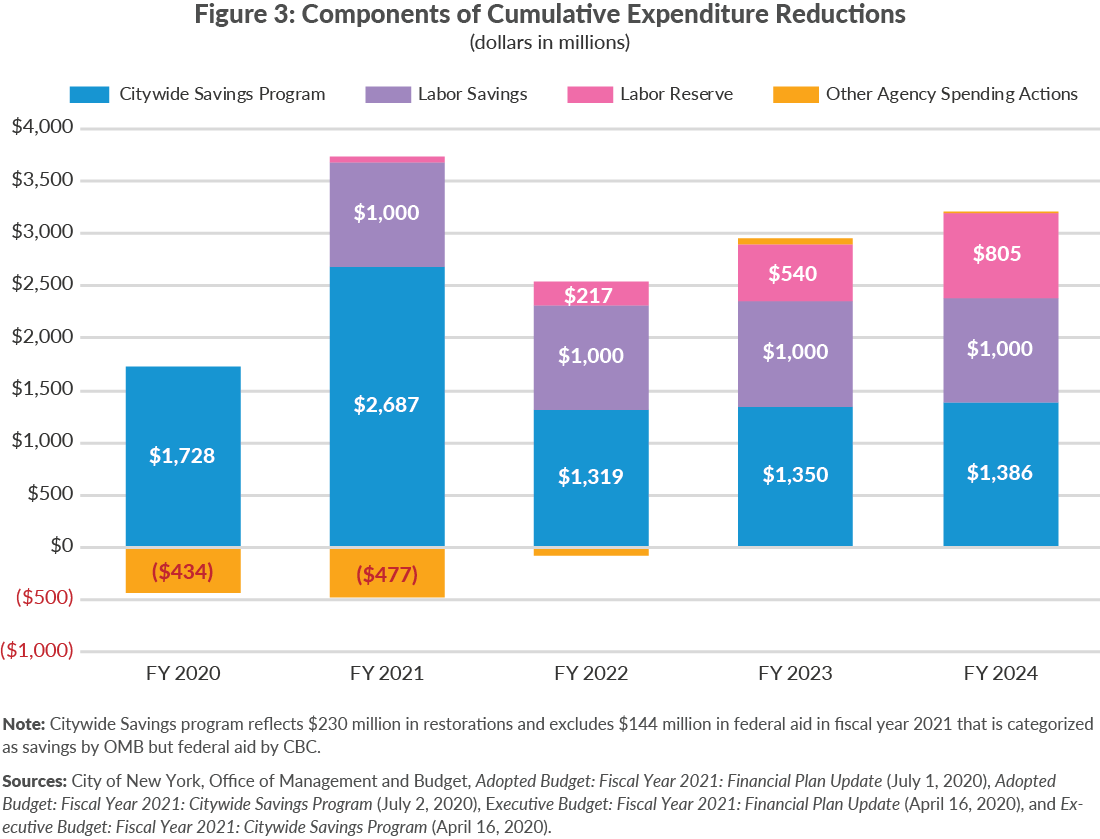

Planned expenditures were reduced by $1.3 billion, $3.3 billion, $2.5 billion, $2.9 billion, and $3.2 billion, in fiscal years 2020 to 2024, respectively. These reductions are the combination of savings programs, expected labor savings, reduction of the labor reserve, and other agency spending actions, including City Council discretionary funds. (See Figure 3.) Importantly, some reductions lack specificity or are unlikely to be realized.

Citywide Savings Programs

Citywide Savings Programs (CSPs) in the Executive and Adopted Budgets, net of cuts that were restored and COVID-19 related federal aid, totaled $1.7 billion in fiscal year 2020 and $2.7 billion in fiscal year 2021.4 However, projected savings in fiscal years 2022 to 2024 were just $1.3 billion annually. (See Figure 4).

About half of the fiscal year 2021 savings do not recur because they are heavily reliant on one-time spending re-estimates, funding shifts, or underspending as a result of the pandemic. (Figure 4.) In addition, service reductions were mostly one-year suspensions due to the pandemic, and save $430 million in fiscal year 2021, and slightly less than $110 million annually thereafter.

Eleven percent of CSP savings are from new City revenue, including water and sewer rental payments, increased reimbursement for ambulance transports, and a parking rate increase in the outer boroughs. Savings from refunding debt and lower-than-expected interest rates generate about 10 percent of savings.

Less than one-fifth of the cumulative savings is due to increasing operating efficiency—revamping the provision of services to reduce costs without reducing the level of service. Efficiency initiatives only provide about $270 million of the savings in fiscal year 2021 and about $310 million per year in fiscal years 2022 to 2024—just 0.39 percent of the fiscal year 2021 adjusted City-funded budget.5 In fiscal years 2022 to 2024, this figure is between 0.42 percent and 0.44 percent of City-funded spending.

Labor Savings

The budget includes $1 billion in recurring savings to be negotiated with the City’s municipal labor unions. Labor has provided savings in prior recessions, but no plan was in place at the time of budget adoption. The Mayor has said that absent an agreement yielding $1 billion in savings, the City would lay off 22,000 workers beginning in October.

Labor Reserve

The City set aside funds for future collective bargaining agreements in a “labor reserve” sufficient to extend the current pattern of wage increases to unsettled contracts and to provide 1 percent annual raises in the next “round” of bargaining.6 In the Adopted Budget labor reserve funding for two 1 percent raises was eliminated, essentially amounting to a two-year wage freeze with savings that increase from $53 million in fiscal year 2021 to $805 million in fiscal year 2024.7

Other Agency Spending Actions

Spending reductions were offset by other spending actions, mainly spending for City Council discretionary initiatives, the Cure Violence program, cultural affairs, and funds to prepare vacant units at the New York City Housing Authority for occupancy, among other programs.8 Cumulative spending actions increased City-funded expenditures by $434 million in fiscal year 2020 and $477 million in fiscal year 2021, which consisted mostly of $375 million in City Council discretionary funds.9 New spending for fiscal year 2022 totaled $84 million, while the net impact in fiscal years 2023 and 2024 was a savings of $63 million and $24 million, respectively.10

Federal Aid

Federal aid totaling $1.9 billion was used to close the gaps in fiscal year 2020 ($1.1 billion) and fiscal year 2021 ($750 million, including $144 million for the Emergency Shelter Grant and Staten Island Ferry operations included in the CSP). 11 This funding was primarily through the enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) and the U.S. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, as well as through Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which provided $172 million in disaster funds for overtime costs that were originally City-funded.12 In addition to the $1.9 billion, the City expects to receive $2.5 billion in FEMA aid as reimbursement for pandemic responses costs.13

Reserves

The City used $4 billion of its reserve funds and the Retiree Health Benefits Trust Fund (RHBT) to close the gaps in fiscal years 2020 and 2021. Of the annual General and Capital Stabilization Reserves $280 million was used in fiscal year 2020 and $1.15 billion in fiscal year 2021, which left$100 million in the fiscal year 2021 general reserve, the minimum required by the City Charter and Financial Emergency Act. The General Reserve and Capital Stabilization Reserve remain at $1.25 billion annually in fiscal years 2022 through 2024.14

The remaining $2.6 billion came from a drawdown of the RHBT, which reduced the RHBT balance from $4.7 billion to $2.1 billion in fiscal year 2021.15 This fund was created in 2006 to accumulate resources to fund the health benefits of retired city employees; the City’s liability for these retiree benefits, commonly known as other postemployment benefits (OPEB), is $105 billion.16

Actions Taken Were Insufficient For Tackling the Outyear Deficits and Preparing for Risks

The actions used to balance the fiscal year 2021 budget provided short-term solutions and did not make sufficient progress in paving a path to stabilize the City’s finances over the mid-term and long-run. The balanced budget is vulnerable, with substantial downside risk, including possible State cuts to local assistance and tax revenue collections that depend on a recovery starting in calendar year 2021, which recent economic data and the evolving path to controlling the pandemic call into question.

CSP Lacks Recurring Efficiency Savings and Includes Unrealistic Projections

The CSP mirrors prior de Blasio Administration efforts—significant reliance on re-estimates and funding shifts, with minimal recurring savings from efforts to improve efficiency. And this year, the CSP included some proposed savings that will be hard to achieve. For example, the City is expecting to reduce New York Police Department overtime by $336 million (56 percent) and Department of Correction overtime by $67 million (44 percent) in fiscal year 2021 without detailed operational plans. Prior efforts to control uniformed overtime have had limited success. In addition the Fire Department expects to collect $96 million more in ambulance fees in fiscal year 2021 and $128 more annually in fiscal years 2022 to 2024 through “strategies to increase reimbursement.”17 This would represent a 42 percent increase in fiscal year 2021 and a 56 percent increase in fiscal years 2022 to 2024. In fiscal year 2019 ambulance fee revenue was $179 million, a shortfall against the budgeted amount of $205 million.18

Labor Savings Are Reasonable and Need to Be Identified Promptly

Labor savings should be a part of the City’s budget balancing efforts. The $1 billion savings target is a reasonable 2 percent of total municipal workforce expenditures; however, to date no plans or process to achieve this target have been initiated, even with an October deadline that the Mayor has said must be met to forestall 22,000 layoffs of municipal workers.19

CBC has identified approaches to generate these savings and stave off layoffs. A package that consolidates union welfare funds, phases in employee health insurance premium contributions, changes work rules to improve productivity, and shrinks the workforce through attrition could generate savings of these magnitude. Furthermore, the City and labor could identify savings by agreeing to change other collectively bargained benefits, including vacation days, sick leave, work hours, and even contractually agreed upon raises and steps.

Shrinking the workforce through attrition is both possible and preferable to layoffs. Approximately 6 percent to 7 percent of City employees—over 20,000 individuals—leave City employment each year.20 If the City filled only a portion of those positions, broadening the existing partial hiring freeze, savings would be substantial. While attrition is less targeted than layoffs, refilling positions strategically can allow the City to focus on maintaining critical services. Prior recessions have relied substantially on attrition with more targeted layoffs aimed at improving programmatic operation.

Out Year Gaps Reduced, But Downside Risks Remain

Adopted budget actions partially offset future revenue shortfalls; however, the gap for fiscal year 2022 is now $1.7 billion larger than it was in January. The efforts taken in this budget were insufficient and substantial downside risks remain.

Forecast tax revenues assume an 8.7 percent increase in fiscal year 2022, but a slower recovery could reduce that rate and open wider gaps. This forecast is not out of line with history—tax revenues grew 10.3 percent in fiscal year 2004 and 8.4 percent in fiscal year 2011—however, this crisis differs from a “traditional” economic recession with continuing likely actions to control the pandemic affecting the timing and strength of a recovery.

The State’s fiscal health is as bad or even worse than the City’s; New York State faced a $7 billion budget gap before the pandemic hit and its enacted budget gap closing plans include $8 billion in unspecified local cuts in the absence of federal aid.21 These cuts would be in addition to the impact on State education aid the City’s Adopted Budget already included in fiscal years 2022 to 2024—about $1 billion annually.22 Possible reductions in State aid are a substantial risk for the City, which receives about 40 percent of State education aid.

Lastly, there are risks to the City from managing spending. In addition to optimistic assumptions, like a 56 percent reduction in police overtime, the City frequently underestimates future spending needs. For example, fiscal years 2022 and out do not currently include funding for either the Fair Fares program or the additional MTA paratransit contribution.23 And, while a wage freeze is reasonable in this economic situation, budgeting for them at the end of an administration without the agreement of labor presents a huge challenge for the next Mayor.

Conclusion

The City budget for fiscal year 2021 is balanced, but that balance is based on actions yet to be taken and assumptions that may prove too optimistic, both in terms of revenue to be received and savings to be achieved. Similarly, the outyear budget gaps may be larger than currently forecast, especially if State aid cuts are enacted or the economic recovery is slower than currently forecast. The City should undertake a thorough review of agency programs and operations to identify recurring savings, reduce the City’s workforce through attrition, and implement recurring labor savings.

The Administration continues to lobby for additional federal aid and long-term borrowing authority in an effort to close budget gaps, rather than pursue an aggressive strategy to identify additional recurring spending reductions. While additional federal aid would be appropriate and in line with support given to localities in prior recessions, the City should not turn to long-term borrowing to address an imbalance in revenues and expenditures; borrowing should be a last resort.

Download Presentation

NYC FY 2021 Adopted Budget: Short-Term Balance, Long-Term ChallengeFootnotes

- Hotel tax revenue declined by 25 percent and 58 percent in fiscal years 2020 and 2021, but represented less than 7 percent of the total decline in either of those years. See: City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Revenue (July 2, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/adopt20-rfpd.pdf, and Preliminary Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Revenue (January 16, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/jan20-rfpd.pdf.

- Net reductions reflect both increases and decreases in many revenue streams. The net reductions in fiscal years 2020 and 2021 would have been greater if not for a rental payment from the Water Board of $128 million in fiscal year 2020 and $137 million in fiscal year 2021. Some reductions in fiscal year 2021 include $70 million less in parking fines, $6 million less in street fair commissions, and $11 million less in parks concession revenue. See: City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Revenue (July 2, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/adopt20-rfpd.pdf, and Executive Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Revenue (April 16, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/exec20-rfpd.pdf.

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Executive Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Message of the Mayor (April 16, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/mm4-20.pdf.

- The Adopted Budget restored $230 million in cuts proposed in the Executive Budget; the CSP savings presented in this blog have been adjusted to reflect the restoration. Additionally, $144 million in city-fund savings in fiscal year 2021 are due to additional CARES federal aid; CBC has reflected those funds in the federal aid item and reduced the CSP total accordingly. See: City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Citywide Savings Program (July 2, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/csp6-20.pdf,

- Categorization by CBC and does not correspond to OMB categorization. Reflects CBC adjusted city-funded expenditures.

- As collective bargaining agreements are settled, funds are transferred from the reserve to agency budgets.

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Financial Plan Reconciliation (July 2, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/adopt20-fprecon.pdf.

- These are City-funded expenditures. In addition, pandemic-related expenditures reimbursed by the federal government are not reflected here. As of the final modified fiscal year 2020 budget, COVID-19 related spending was $4.0 billion. See: City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Financial Plan Reconciliation (July 2, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/adopt20-fprecon.pdf; and Office of the New York City Comptroller, New York by the Numbers: Weekly Economic and Fiscal Outlook (No. 9, July 13, 2020), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/new-york-by-the-numbers-weekly-economic-and-fiscal-outlook-no-9-july-13-2020/.

- Fiscal year 2021 Council initiatives were 17 percent lower than fiscal year 2020, when Council initiatives were $454 million. See: City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Budget: Fiscal Year 2020: Financial Plan Update (June 19, 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/fpu6-19.pdf.

- These spending actions include technical adjustments that can either increase or decrease spending and many of the programmatic funds for fiscal year 2021 were not baselined in fiscal years 2022 to 2024. Furthermore, the City made adjustments to pension funding, include a pension audit reserve, in fiscal years 2022 to 2024 that reduced planned contributions. These pension changes do not reflect investment earnings in fiscal year 2020.

- The total federal aid used to close the gap is lower than the projection in April 2020, in part due to more information about eligible expenses and actual revenue levels.

- Federal funding used to close the gap was $742 million for FMAP ($138 million in fiscal year 2020 and $605 million in fiscal year 2021), $793 million in CARES funding ($790 million in fiscal year 2020 and $3 million in fiscal year 2021), and $172 in FEMA funding for overtime in fiscal year 2020. From: City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, email to Citizen Budget Commission staff (July 18, 2020).

- Federal aid for COVID-19 expenditures is not definite. If the City receives less than expected, this could negatively impact the budget gap by requiring additional City funds. FEMA COVID-19 aid is $2,665 million in fiscal years 2020 and 2021, less the $172 for overtime used to close the gap. From: City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, email to Citizen Budget Commission staff (July 18, 2020).

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Executive Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Financial Plan Update (April 16, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/fpu04-20.pdf, and Adopted Budget: Fiscal Year 2020: Financial Plan (June 30, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/fp6-20.pdf.

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Executive Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Financial Plan Update (April 16, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/fpu04-20.pdf; and Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comprehensive Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2019 (October 31, 2019), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/CAFR2019.pdf.

- The CBC does not consider the RHBT a de facto Rainy Day Fund. See: Ana Champeny and Maria Doulis, Short-Term Goals for Long-Term Debt: Time to Prioritize Reducing New York City’s Liabilities, Citizens Budget Commission (September 18, 2018), https://cbcny.org/research/short-term-goals-long-term-debt.

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Adopted Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Citywide Savings Program (July 2, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/csp6-20.pdf.

- City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, email to Citizen Budget Commission staff (July 18, 2020)..

- City of New York, Office of the Mayor, Transcript: Mayor de Blasio Holds Media Availability (June 26, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/473-20/transcript-mayor-de-blasio-holds-media-availability.

- City of New York, Department of Citywide Administrative Services, New York City Government Workforce Profile Report (Fiscal Year 2017), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/dcas/downloads/pdf/reports/workforce_profile_report_2017.pdf.

- Dave Friedfel and Charles Brecher, New York State’s Hard Choices: Next Steps to Address Fiscal Stress, Citizens Budget Commission (May 22, 2020), https://cbcny.org/research/new-york-states-hard-choices.

- NYC frequently assumes state education aid will be higher than it ultimately is, in addition to not having adjusted fiscal year 2022 to 2024 education aid forecasts to reflect the reductions in the state enacted financial plan. See: Ana Champeny, Hard Choices that Can Balance New York City’s Budget, Citizens Budget Commission (June 10, 2020), https://cbcny.org/research/hard-choices-can-balance-new-york-citys-budget.

- State enacted budget required the City to increase contribution to MTA. City added $63 million for FY21 only. City of New York, Office of Management and Budget, Executive Budget: Fiscal Year 2021: Financial Plan Reconciliation (April 17, 2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/exec20-fprecon.pdf.