Prioritizing the MTA's Critical Capital Needs

What to Do When You Can’t Do It All

Executive Summary

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) has significant needs for capital investment, from signal modernization and track improvements to new subway and train cars to making stations across the system accessible. Many of these investments are critical to bring the system’s infrastructure to a state of good repair (SGR) and modernize the system to increase safety and speed. The MTA also plans to expand the system’s reach and service, including extending the Second Avenue Subway.

To guide its investments since 1982, the MTA has used 5-year capital plans, generally informed by 20-year needs assessments. Over time, the MTA’s capital plans and investments have not kept up with accumulated and forecast needs; furthermore, the plans are often not fully committed within the five-year horizon. The deterioration was so severe by 2017 that system performance significantly suffered, and the State initiated a special “subway action plan” to restore service to a reasonable level.

With nearly two-and-a-half years left until the next capital plan, this is a critical juncture at which to assess the state of execution and financing for the MTA’s outstanding projects and recommend actions to help the MTA prioritize its capital investments now and in the future. In fact, the MTA passed an amendment to the 2020–2024 capital plan just last month that increased funding for some priorities, such as signal upgrades, while delaying others, such as the purchase of new rolling stock that has been hampered by production delays.

Given the number of outstanding projects including those delayed during COVID, the MTA will not commit more than $25 billion of its currently planned projects in the originally desired timeframe, even as it successfully increases its annual capital commitments. Furthermore, at least 20 percent of the planned funding for capital improvements is now unaffordable or at risk; ultimately these resources, including all planned congestion pricing revenue, are essential to bring the system to a state of good repair and modernization. Fortunately, there is positive movement on congestion pricing, with the release of the Environmental Assessment (EA), scheduled public input and naming of the Traffic Mobility Review Board (TMRB) members.

The MTA has placed a high priority on SGR, allocating the majority of the 2020-2024 capital program for SGR, normal replacement, and system improvement projects, and increasing focus on SGR projects during COVID.1 Still, even with improvements in contracting speed, the MTA is highly unlikely to complete its planned projects in a timely fashion, and there is a risk that the system will not be brought to a state of good repair in the foreseeable future. Thus far, the MTA has not laid out a detailed, prospective multiyear project plan that would allow the public to know which remaining projects are prioritized through 2024, when they are expected to be completed, the impact on the system’s state of good repair, and the likelihood that the system’s service would be able to be maintained and not deteriorate due to disrepair.

The Citizens Budget Commission’s (CBC) analysis of the financing plan, prior commitments, and current capital plans found that:

- The MTA has $52.9 billion of projects still uncommitted from the 2020-2024 and two prior five-year capital plans, including $7.5 billion for the Second Avenue Subway and Sandy projects supported by federal funds and projects delayed due to pandemic-caused slowdowns;

- Over the past six years, the MTA’s annual capital commitments averaged $7.1 billion;

- The MTA has implemented contracting improvements, including alternative contracting vehicles and project bundling, which have increased its capacity; the authority forecasts commitments of $8.2 billion this year;

- Given the MTA’s recent record and dedication to increasing capital throughput, continuing improvements are probable and will, in fact, be necessary to successfully commit contracts in the desired timeframes during the next plan period;

- $30.2 billion of projects would still be uncommitted when the current plan period ends in 2024, assuming annual commitments increase 15 percent to this year’s $8.2 billion target;

- If annual commitments increase to $10.0 billion, $27.6 billion of projects would be uncommitted;2

- At the $8.2 billion rate, outstanding planned projects would not be completed until 2028, hampering the ability to implement projects in the 2025-2029 capital plan;

- At the $10.0 billion rate, outstanding planned projects would be completed during 2027;

- At least $12.0 billion, or 20 percent, of future planned capital financing is at risk or unaffordable, but all is critical to bring the system to a state of good repair and support essential modernization;

- $11.5 billion of planned spending and borrowing is unaffordable due to the MTA’s structural deficit;

- $500 million is at risk from lower-than-expected revenue from the new dedicated real estate transfer tax;

- An additional $3.0 billion may be at risk if excessive subsidies and credits or price-induced reductions in volume weaken congestion pricing revenue; and

- Another $3.4 billion is only available for system expansion and not to bring the current system to a state of good repair.

Based on these findings and prior work, CBC recommends that the MTA specify and prioritize which projects it will commit through the end of 2024, examine and prioritize the remaining outstanding projects, create a comprehensive 2025-2029 capital plan, and work diligently to increase capital capacity and reduce capital costs. Specifically, CBC recommends that the MTA:

- Publish a priority list of projects, estimated to total $23 billion to $25 billion, that will be committed by 2024;

- Focus on state of good repair, normal replacement, and system improvement projects;

- Prioritize projects that (in order): maintain safety, restrain maintenance costs, reduce capital cost by packaging contracts, improve systems that require SGR investment ahead of modernization, geographically disperse station accessibility projects, and invest in system redesign that reduces ongoing operating costs;

- Publish a planned schedule for the remaining projects from the 2010-2024 capital plans;

- Prioritize these based on the above criteria, and integrate their schedule with the 2025-2029 capital plan;

- Continue to include congestion pricing’s full estimated revenue, which is essential to support a capital plan robust enough to bring the system to a state of good repair;

- Develop an ambitious and solidly financed 2025-2029 capital program incorporating projects from prior plans and current needs;

- Base this program on a published 2023 needs assessment, with projects that are prioritized on the above criteria, realistically financed, and include details at the project level;

- Use contracting and financing capacity on SGR and modernization projects, before using additional capacity on system expansion;

- Incorporate thoughtful consideration of the evolution of post-pandemic travel and commuting patterns, and evolving technology and transportation modes;

- Prioritize increasing operational efficiency to help eliminate the structural deficit, possibly creating the capacity to issue debt for capital when the operating budget’s recurring revenues and expenditures are appropriately balanced;

- Continue to work with the federal and State governments to implement congestion pricing by 2023 to provide critical revenues, environmental and congestion benefits, and support increased ridership;

- Continue procurement improvements and reforms to increase capacity, and better align unit costs with national and international standards for major capital maintenance and system expansion; and

- Continue to improve capital execution to increase capacity, including FASTRACK and partial- or full-line shutdowns to accelerate projects.

Without additional significant improvements that increase the speed of capital projects contracting and execution, the MTA’s transit systems may struggle to return to a state of good repair, which could risk the City’s and region’s economic growth and competitiveness.

Introduction

In 1982, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) embarked on a new program of five-year capital plans intended to bring its subway and commuter rail systems to a state of good repair (SGR) following years of neglect. Once the neglect was overcome, the capital plans were expected to keep the system in a state of good repair with normal replacement (NR) of assets, implement system improvements (SI), and expand service.3

These capital plans were intended, and since a 2019 State law have been required, to be informed by a 20-year needs assessment. The most recent assessments identify “asset condition, asset age vs. useful life, and asset performance vs. an identifiable performance standard (including safety and reliability),” and present and prioritize investments for successive five-year capital plans to maintain, rebuild, and expand the system.4 Over time, the MTA’s capital plans and investments have not consistently kept up with accumulated and forecast needs.5 Plans regularly are not committed within the five-year horizon. The deterioration was so severe by 2017 that system performance significantly suffered, and the State initiated a special “subway action plan” to restore service to a reasonable level.

The divergence from this appropriate planning process widened when the MTA did not finalize or release the 2017 needs assessment, intended to inform the 2020-2024 capital plan. This and the plan’s limited transparency about project schedules, costs, and priorities within the five-year window, were identified as problems immediately upon release of the 2020-2024 capital plan.6 While the MTA reports using internal assessments to inform its current capital program, the lack of a published needs assessment leaves stakeholders—including riders, drivers, taxpayers, policy makers, experts, and the press—unable to determine the extent to which the 2020-2024 capital program is addressing normal replacement needs, appropriately investing in system improvements, and achieving and maintaining a state of good repair for asset classes and systemwide. Information on contracted projects and projects planned through 2023 is now available, while information on the planned schedules and impacts of the balance of the outstanding projects remains publicly unavailable.

Following a forensic audit of MTA capital practices, in 2019 the State codified the requirement that the MTA submit the 20-Year Needs Assessment to the Capital Program Review Board every five years beginning on October 1, 2023, in time for the next capital program cycle.7 This requires the MTA to update its asset inventory and conduct a needs assessment that identifies all the capital needs over the next 20 years, which supports and informs the prioritization of projects to be included in the five-year capital program.

Done well, this should be the basis of a well prioritized and realistic five-year 2025-2029 capital plan. However, due to projects from the current and two prior plans that remain to be committed, including those delayed by the pandemic and lagging federal aid, current planned investment is severely misaligned with the original planned timing of those investments. The level of outstanding projects at the end of 2024 will represent a very significant share of capital projects that the MTA can reasonably execute during the 2025-2029 period. Furthermore, there is limited information on how current and forthcoming projects will affect the system’s SGR. Together, these problems may result in executed projects not being aligned with the most critical long-run needs. The 2025-2029 capital plan will include tens of billions of dollars of new projects that will co-exist alongside, instead of being integrated with, the tens of billions of dollars of previously identified projects still to be committed.

With almost two and half years left in the current capital plan period, this is a critical juncture at which to assess the state of execution and financing for the MTA’s outstanding projects and recommend course corrections to help the MTA prioritize its capital investments now and in the future. The MTA itself approved Amendment #2 to the 2020-2024 capital plan in July 2022 to make some of these types of changes.8 This brief assesses:

- The funds available to finance the MTA’s capital program; and

- The level of capital commitments the MTA has executed annually.

Based on these findings and prior work, CBC recommends that the MTA specify appropriately prioritized projects that it will commit through the end of 2024, prioritize and schedule its remaining outstanding projects, create a comprehensive 2025-2029 capital plan, and continue its diligent efforts to increase capital capacity and reduce capital costs. Consistent with CBC’s long-standing position, this report recommends ensuring that the MTA's capital contracting and financing capacity first be dedicated to bringing the system to and maintaining it at a state of good repair. Once that and essential modernization is achieved, additional contracting and financing capacity could be allocated to system expansion.

At Least $12.0 Billion in Planned Capital Funding is at Risk or Unaffordable

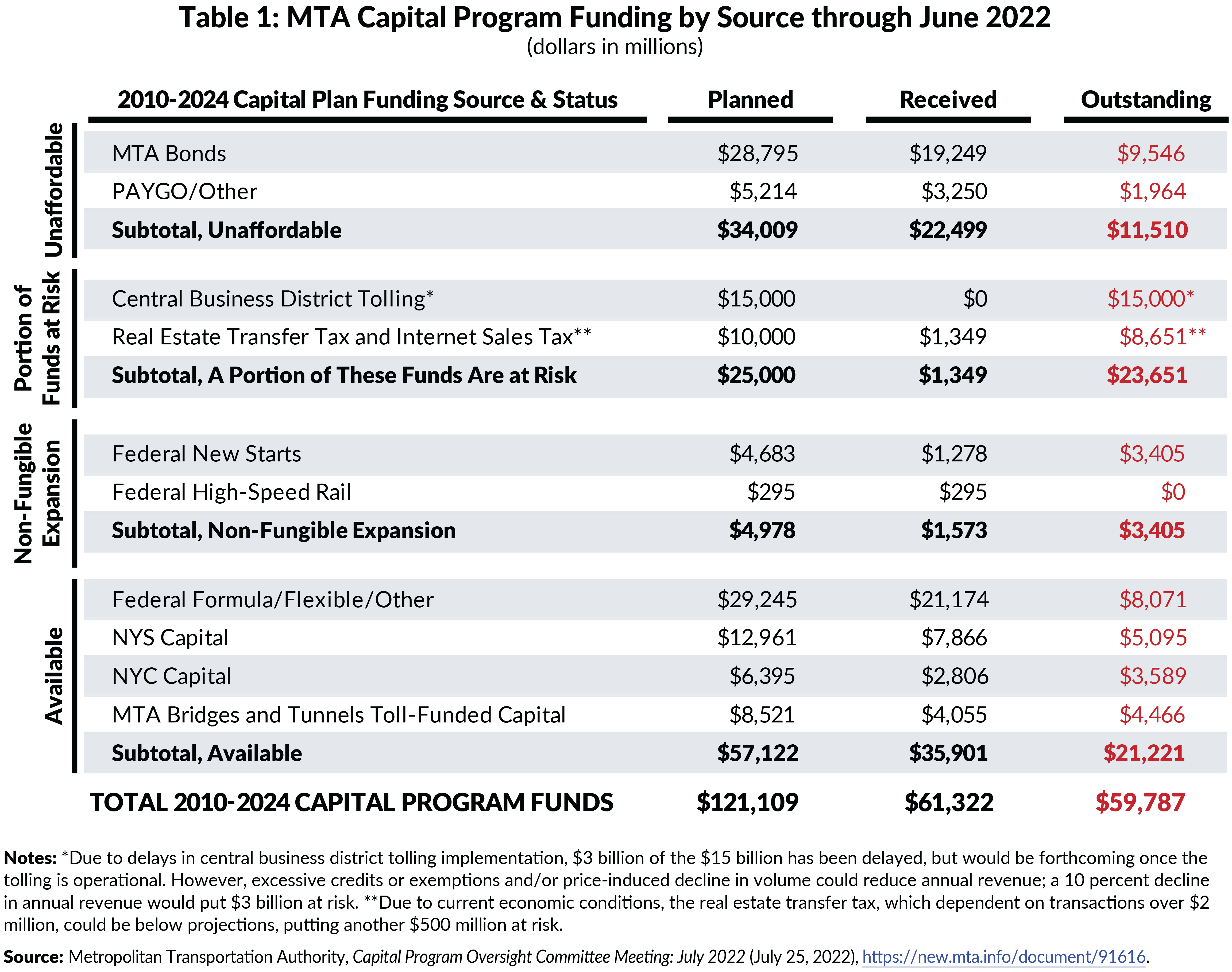

MTA capital investments are supported by New York State and New York City appropriations, several federal funding streams, dedicated tax revenues and tolls, MTA-supported bonds, and pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) funding from its operating budget. The MTA identified $121.0 billion to fund three 5-year capital plans covering 2010 through 2024.

While most of the outstanding funding will be available, at least $12.0 billion is at risk or unaffordable. (See Table 1.) The majority, $11.5 billion of MTA pay-as-you-go funding or long-term debt, is unaffordable due to the MTA’s structural operating deficit. Additionally, $500 million is at risk due to weakness in a new dedicated real estate transfer tax.9 Another $3.0 billion may be at risk due to uncertainty about the implementation of congestion pricing. Thus, the capital financing shortfall is at least 20 percent of the $59.8 billion in funding that has not yet been received and could be up to 25 percent. Ultimately, the level of identified resources, including all planned congestion pricing revenue, is essential to bring the system to a state of good repair and for modernization.

Planned own-source funding of $11.5 billion from long-term financing and PAYGO spending is unaffordable given the MTA’s current fiscal condition.10 The MTA has an underlying structural operating budget gap exceeding $2.5 billion annually.11 Absent significant changes in the fiscal fortunes of the MTA’s operating budget, it is fiscally unsound for the MTA to issue new debt whose debt service is not supportable due to the structural deficit.12 The MTA recently reduced this financing gap from $13.2 billion by wisely substituting $1.7 billion additional federal funds available due to the passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) for originally planned MTA long-term bonds.13

CBC has recommended operational improvements that could reduce the MTA’s operating costs by up to $2.9 billion annually.14 Implementing all or a portion of these, while challenging and requiring collaboration with labor, should be a significant part of the solution to closing the structural gap, increasing the ability for the MTA to issue its own debt. Furthermore, while not now considered likely, especially given updated ridership projections, ridership returning to 2019 levels could mitigate roughly half of the structural gap.

There is some risk to fully realizing a portion of $8.7 billion from the real estate transfer tax and the sales tax intercept, and $15.0 billion from the Central Business District Tolling Program (CBD, or congestion pricing).15 Receipts from the recently enacted real estate transfer tax were below expectations in 2020 due to a slowdown in high-value residential transactions. While the market recovered in 2021 and revenues met expectations, rising inflation and interest rates cooling the real estate market and higher risk of a recession may restrain revenues from this economically sensitive tax. If revenues are 10 percent below pre-pandemic forecasts, available capital funding would be roughly $500 million lower.

Of greater concern is the delay and ultimate design of congestion pricing. The full value of planned congestion pricing revenue is necessary to bring the system to a state of good repair and for modernization. The delay has already cost $2 billion in forgone revenue in 2021 and 2022, with another $1 billion likely forgone in 2023. While this has not yet affected the pace of capital projects and may not in 2023 due to other available resources and the lag between capital commitments and needed financing, it has had a significant opportunity cost since the funds were not available to offset other financing sources. Recent progress in implementation, including establishing the Traffic Mobility Review Board that will recommend the charges and release of the Environmental Assessment (EA), is welcome news as delay past 2023 would pose a significant problem for execution of the capital plan.

The ultimate design of the congestion charge may pose a substantial risk. Some have called for significant exemptions and credits to offset the congestion charge for various constituencies, a position with which CBC disagrees. While the law requires the charge to be sufficient to raise $1 billion annually, significant credits and exemptions may lead to a high congestion charge for those who pay, as shown in the fee structures modeled in the EA, and a lower charge would yield less revenue.16 If, for example, this or a price-induced decline in vehicle traffic were to cause congestion charge revenue to be 20 percent lower than expected, capital funding also would be 20 percent, or $3 billion, lower.

Federal funds totaling $3.4 billion are likely available but have the important distinction of not being easily repurposed by the MTA. These primarily are comprised of New Starts funds planned to support the next phase of the Second Avenue Subway project. These funds cannot be used for non-expansion purposes or shifted to another expansion project without reapplying to the federal government.

Approximately $21.2 billion of funding can be considered secure and available. Federal formula grants, flexible funds, and other select federal sources will provide $8.1 billion, including an increase in formula funding from the IIJA.17 State and City funding—$5.1 billion and $3.6 billion, respectively—is subject to appropriations; however, the State has budgeted most of its capital commitments and its Fiscal Year 2020 Enacted Budget obligated the City to meet its share.18 Bridges and Tunnels toll revenue has been relatively strong and following past practice will be used to support $4.5 billion in MTA capital projects.19

MTA Will Have $28 Billion to $30 Billion in Previously Planned Projects Outstanding When It Starts Its Next Capital Plan

Capital delivery capacity is a function of institutional capacity to procure and manage projects, procurement and contracting strategies, funding availability, type of projects being procured, and the availability of qualified contractors. Furthermore, decisions about maintaining expected levels of service also affect annual capital commitment volume. Once funds are included in an approved capital program, MTA Construction and Development (MTA C&D) may move forward with a project. For projects executed by external contractors, staff put a project out to bid, award a contract to a bidder, and assign an internal or externally contracted consulting project manager. Other projects are managed and executed internally by MTA staff.

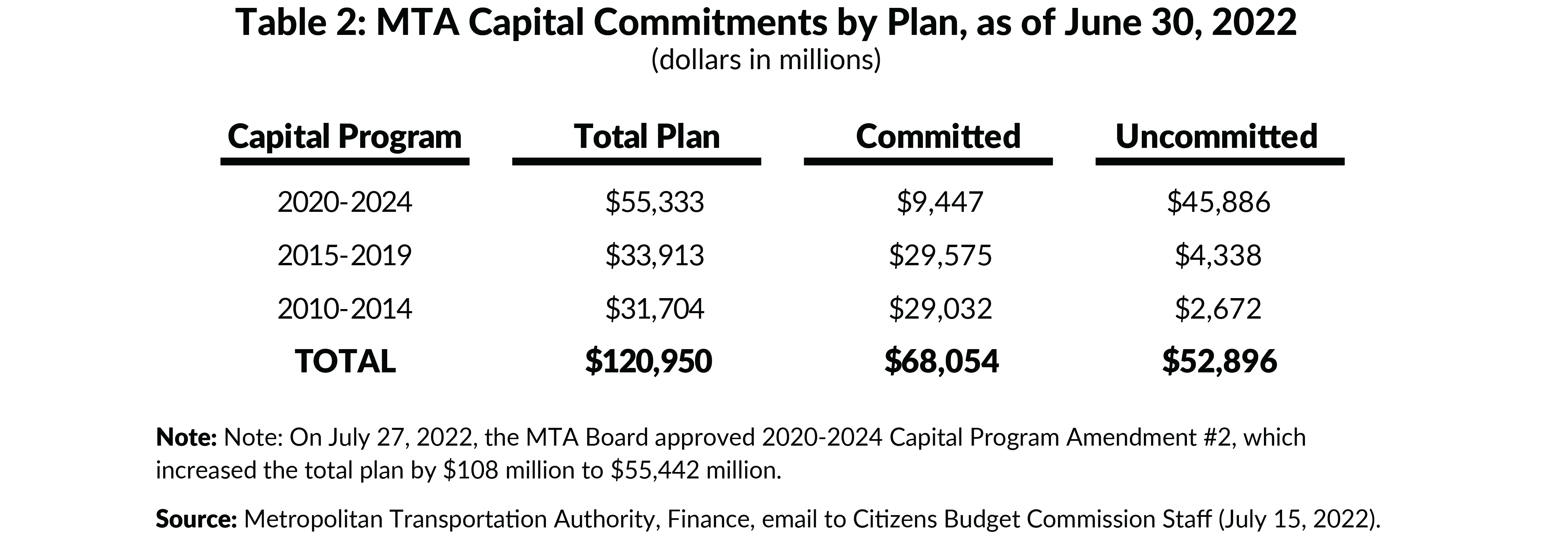

As of June 30, 2022, the MTA committed $68.1 billion of the $121 billion planned for 2010 to 2024, leaving $52.9 billion uncommitted. (See Table 2.) While most of the uncommitted projects are in the 2020-2024 plan, $7.0 billion from the 2010-2014 and 2015-2019 plans has not been committed yet, just under half of which is for the second phase of the Second Avenue Subway and Sandy projects supported by federal funds.20

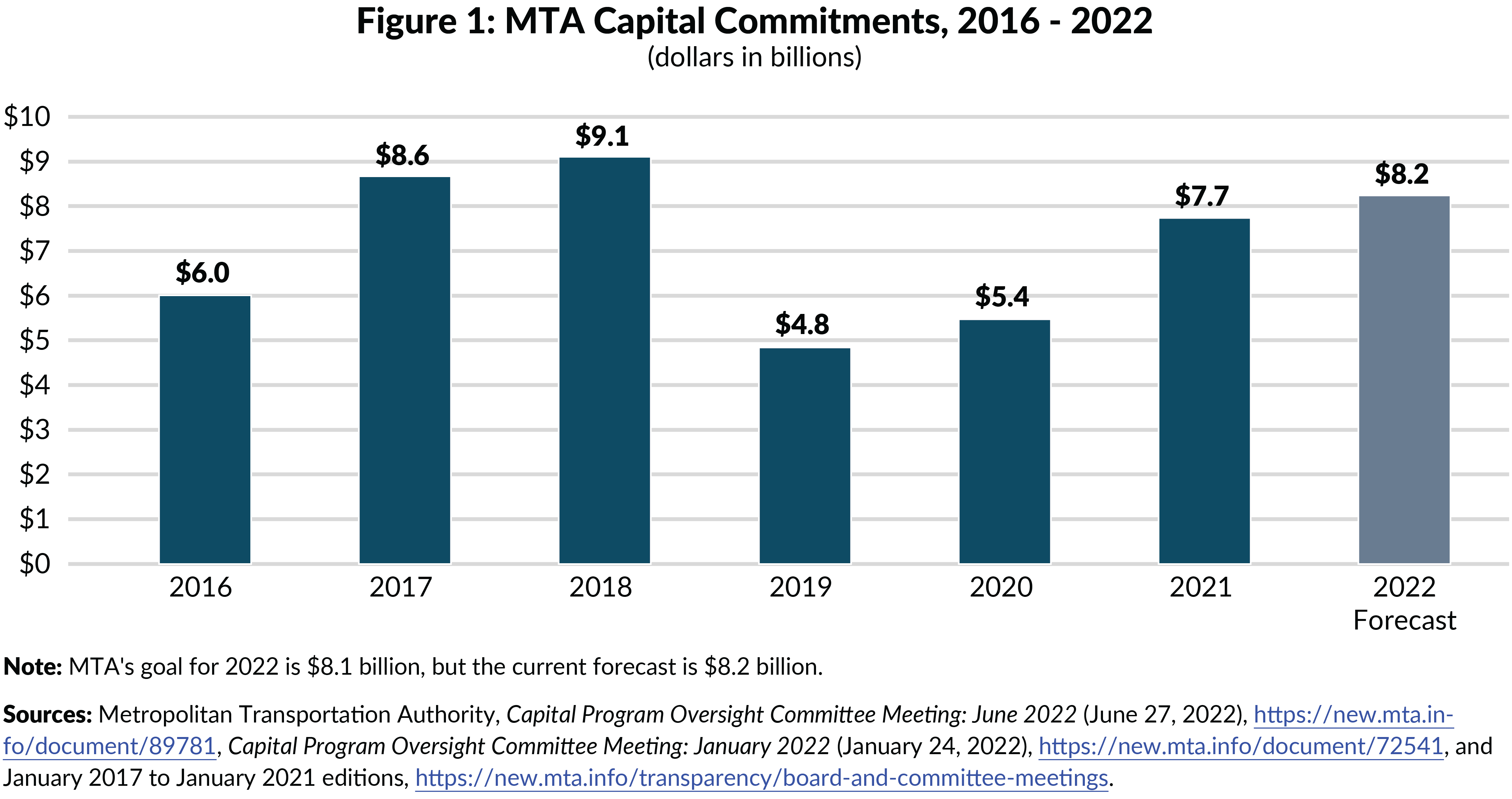

Over the last six years, the MTA’s annual capital commitments averaged $7.1 billion. (See Figure 1.) The restructuring of the MTA’s capital construction activities and creation of the new MTA C&D unit has and hopefully will continue to increase the MTA’s capital capacity over previous levels. MTA C&D reports increased contracting speed with new procurement methods and bundling contracts and projects, among other reforms.

There was a temporary slowdown of commitments during the pandemic, through which the MTA importantly focused on SGR projects and accelerated execution of projects already in process. As pandemic constraints subside, the MTA projects to commit $8.2 billion in 2022. If this higher rate is maintained, the MTA would commit another $22.8 billion of projects in addition to those identified in Table 1 by the end of 2024. This would leave $30.2 billion of projects from the three prior plans still not committed when the MTA starts its 2025-29 capital plan. At this rate, the current projects would not be committed until about eight months into 2028, three-quarters of the way into the next plan period.

Given the track record and approach, continuing commitment speed improvement appears possible and will have to be significant for the MTA to successfully commit contracts in the desired timeframes during the next plan period. If the MTA were able to increase its commitments to $10.0 billion annually over the next two years, it would start the next capital plan period with $27.6 billion of outstanding projects, which it would not be able to complete until about nine months into 2027, about half way through the next plan period.

Project Delays Increase Costs and May Negatively Affect Service Delivery

Delayed capital projects increase costs due to additional normal deterioration, extraordinary deterioration of assets due to compounding effects, and construction cost inflation. Delays also may have negative effects on services and maintenance costs.

Since unmaintained assets continually deteriorate, delays increase costs because the assets are in worse condition than anticipated. Decay of some key asset types may also compound other asset decay, increasing costs. For example, the failure of the water management envelope of a below-grade station allows water and winter road salt to penetrate the structure and accelerate deterioration elsewhere.

Furthermore, if projects in the 2020-2024 plan are not completed on time, projects in the 2025-2029 plan will also be pushed back, increasing their cost due to inflation-driven construction cost escalation. Based on the Engineering News-Record, in New York, construction cost inflation over the past decade has averaged approximately 4 percent annually in New York and current economic conditions are contributing to even higher inflation; cost escalation due to multi-year delays can be significant. [21]

Finally, these construction cost increases are on a base cost that is already much higher than other transit systems in the nation and globally. A study of transit costs by the Eno Center that analyzed system expansion projects found that NYC’s costs for the 7 Line Extension and the Second Avenue Subway were far higher than expansion projects in the U.S. and internationally; the per-mile cost for those two projects was approximately 10 times the average cost of 20 other 100 percent tunneled heavy rail expansion projects completed between 2013 and 2021. [22]

Recommendations: Develop and Execute Realistic, Prioritized, Transparent Plans for the Next Two Years and the Subsequent Five-Year Plan Period

The MTA’s current and two prior capital programs consist of roughly $121 billion of projects to address the Authority’s needs for state of good repair (SGR), normal replacement (NR), system improvement (SI), and network expansion (NE). The plans’ projects ostensibly are to be in contract by 2024. However, not all of the funding will be affordable or available, and given the amount of outstanding projects, including those delayed due to the pandemic and awaiting federal funding, the MTA does not have the capacity to commit the volume of outstanding projects in the next 2.5 years.23

The affordable and available funds for projects in this and prior plans are likely $12.0 billion, or 20 percent below what is needed. This shortfall may be more if congestion pricing revenue is not fully realized or delayed, which would be a major setback not just for revenue generation, but also for the associated environmental and congestion benefits. While IIJA provided $1.7 billion through 2024 and may provide more in discretionary grants for electric buses and ADA compliance, the shortfall remains significant.

While this shortfall is problematic and these funds are needed to bring the system to a state of good repair and for modernization, the proximate impediment to completing outstanding projects in a timely fashion is the MTA’s commitment capacity. The authority likely will only be able to commit roughly $22.8 billion more by the end of the current capital plan, assuming it meets its $8.2 billion commitment goal total for 2022 and sustains that level for the next two years.

CBC has long advocated that the MTA prioritize SGR before system expansion. Once that and essential modernization is achieved, additional contracting and financing capacity could be allocated to system expansion. Given the state of the system’s assets and technology, especially signaling, NR and some SI projects in addition to SGR are also critically important to a well-functioning transit system that supports the NYC regional economy and quality of life. More than 80 percent of outstanding projects are for NR, SGR, and SI, not for network expansion. Thus, even these highest priority needs far outstrip the system’s current capacity to contract for projects within desired timeframes. While the MTA’s recent budget modification took some important steps to update and prioritize projects in the 2020-2024 capital plan, additional prioritization is needed as the MTA’s capacity to commit is approximately half of the needs through 2024.

The recently amended capital plan provides some more information on prioritization of projects from the 2020-2024 capital program. For example, the 2020-2024 amended capital plan identifies about $10.0 billion in planned commitments for 2022; this is modestly higher than the $8.2 billion that the MTA plans to commit. The prioritization for 2023 and 2024 is less clear as the amended plan identifies $16.4 billion in 2023 commitments and $21.4 billion in 2024 commitments, far above likely annual commitment levels. Additional information is presented in a pre-solicitation list that identifies projects to be bid in 2022 and 2023.24

This in no way suggests that the balance of outstanding projects not completed by 2024 should be dropped. The MTA then should reexamine and prioritize the outstanding projects, and integrate their schedule with the next capital plan.

The MTA should develop a new 2025-2029 plan, based on the 2023 needs assessment and with consideration of the priority previously planned projects. This plan also should reflect thoughtful consideration of changing post-pandemic commuting patterns and evolving technologies and transportation modes; the MTA should not assume that the pre-pandemic status quo is the best way forward.

More specifically, to build this plan, prioritize projects, and ensure public transparency and accountability, the MTA should:

- Publish a $22.8 billion to $25.4 billion plan that identifies projects that can be committed by 2024;

- Focus on SGR, NR, and SI projects;

- Prioritize these based on the following criteria, in order:

- Critical to safety;

- Reduce or minimize ongoing maintenance costs;

- Reduce capital costs by packaging contracts;

- Improvements, especially signals, that require SGR investment ahead of modernization;

- Geographic dispersion of ADA station prioritization to balance access; and

- Reduce ongoing operating costs, such as those to facilitate one-person train operation readiness, proof-of-payment and railroad turnstiles, and maintenance facilitation.

- Publish the planned schedule for the remaining outstanding projects from the 2010-2024 capital plans;

- Prioritize these on the above criteria, and integrate their schedule with the next capital plan;

- Supported by full realization of congestion pricing revenue, which is essential to support a capital plan robust enough to bring the system to a state of good repair;

- Develop an ambitious and solidly financed 2025-2029 capital program incorporating projects from prior plans and current needs, which is:

- Built on a published, comprehensive 2023 needs assessment based on an objective, interagency-harmonized asset management system;

- Prioritized by the criteria above and using contracting and financing capacity first on projects that bring the system to an SGR and invest in SI, before using additional capacity on system expansion;

- Based on a realistic assessment of available financing, especially own-source funding in light of the fiscal sustainability of the operating budget;

- Detailed at the project level, including project costs, estimated time frames, and dates;

- Responsive to potential changes due to post-pandemic commuting and travel patterns, evolving technology, and transportation modes;

- Increase the efficiency of operations to help eliminate the structural deficit, possibly creating the capacity to issue debt for capital when the operating budget’s recurring revenues and expenditures are appropriately balanced;

- Continue to work with the federal and State governments to implement congestion pricing by 2023 to provide critical revenues, and environmental and congestion benefits, and support increased ridership;

- Continue capital procurement improvements and reform to increase capacity, and align unit costs with national and international standards for major capital maintenance and system expansion; and

- Continue to improve capital execution to increase capacity, including Fastrack, and partial- or full-line shutdowns to accelerate projects.

Much has changed since the 2013 20-Year Needs Assessment. While the Subway Action Plan prioritized over $1 billion for the highest subway needs, the MTA focused on SGR work during the pandemic, and contracting speed is being increased, these steps are not likely sufficient to indefinitely stave off deterioration or ensure the most critical priorities are being addressed. Meanwhile, existing needs grow more costly, and the 2023 20-Year Needs Assessment will inform MTA management and the public alike on how the accumulated backlog of necessary repairs and ongoing needs has evolved and should be prioritized.

The fundamental question for the MTA’s future is how and whether the Authority can accelerate capital procurement and execution enough to attain an SGR and modernize the system, or whether ongoing and compounding deterioration will swamp progress, leading to a decline in the system’s ability to provide the level of service that enhances New Yorkers’ quality of life and fosters a thriving regional economy.

Footnotes

- Following Amendment #2 to the 2020-2024 capital plan, approved in July 2022, the share of projects categorized as SGR, NR, or SI was 66 percent.

- The MTA has communicated to CBC that it believes it will increase commitments even more, and have fewer projects uncommitted by the end of 2024.

- Selma Mustovic and Charles Brecher, Working in the Dark: Implementation of the MTA’s Capital Plan (Citizens Budget Commission, October 20, 2009), https://cbcny.org/research/working-dark-0.

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, MTA Twenty-Year Capital Needs Assessment 2015-2034 (October 2013), https://new.mta.info/document/11976. Ideally, the Authority should have an all-agency asset inventory with the known age and condition of each asset measured against its intended service condition and/or its useful design life or “Useful Life Benchmark” (ULB). Knowing the age, condition, ULB, and replacement cost for all assets, the MTA should be able to forecast the total value of investments necessary to achieve a state of good repair net of normal replacement over the coming capital plan period, or at least to forecast the date at which the gap will be closed given the current pace of investment and of asset aging.

- Jamison Dague, Sisyphus and Subway Stations (Citizens Budget Commission, August 31, 2015), https://cbcny.org/research/sisyphus-and-subway-stations.

- Testimony of Andrew Rein, President, Citizens Budget Commission before the Assembly Standing Committee on Corporations, Authorities and Commissions and Senate Standing Committees on Transportation and Corporations, Authorities and Commissions, Testimony on the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s 2020-2024 Capital Program (November 12, 2019), https://cbcny.org/advocacy/testimony-metropolitan-transportation-authoritys-2020-2024-capital-program.

- N.Y. Public Authorities Law § 1269-c (2022).

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, MTA Capital Program 2020-2024, Amendment #2 (July 27, 2022), https://new.mta.info/document/91711.

- The tax, sometimes referred to as the Mansion Tax, has two components: a 0.25 percentage point increase in the rate on residential transfers in NYC over $3 million and commercial transfer in NYC over $2 million, and a graduated transfer tax for residential transfers in NYC ranging from 0.25 percent for transfers between $2 million and $3 million and reaching 2.9 percent for transfers of $25 million and more. Ana Champeny, “Follow the Money: The MTA’s New Revenues,” Citizens Budget Commission Blog (April 5, 2019), https://cbcny.org/research/follow-money.

- Alex Armlovich, “Light, at the Beginning of the Tunnel: What to Look For in the MTA 2021 July Financial Plan,” Citizens Budget Commission Blog (July 20, 2021), https://cbcny.org/research/light-beginning-tunnel; and Brandon Sanchez, “Federal funds barely dent MTA’s budget deficit,” Crain’s New York Business (November 17, 2021), https://www.crainsnewyork.com/transportation/federal-funds-barely-dent-mtas-budget-deficit.

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, July 2022 Financial Plan Presentation (July 25, 2022), https://new.mta.info/document/91721.

- All budget references herein refer to the MTA’s official cash budgeting approach. On a full accrual GAAP basis, the MTA’s financial position is weaker due to its other postemployment benefit obligations.

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, MTA Capital Program 2020-2024, Amendment #2 (July 27, 2022), https://new.mta.info/document/91711.

- Alex Armlovich, The Track to Fiscal Stability: Operations Reforms for the MTA (Citizens Budget Commission, May 25, 2021), https://cbcny.org/research/track-fiscal-stability.

- The annual revenues from these sources are expected to support that level of long-term borrowing. The budgeted 2-year delay and publicly announced 3-year delay to the MTA’s congestion pricing lockbox has forgone $2 billion in revenue to date and will forego another $1 billion in congestion charges by the time the system is operational. MTA expects municipal bond markets to require a 12-month “proving” period to demonstrate program revenue target achievement before debt issuance is feasible, deferring the beginning of debt issuance for the $15 billion portion of the 2020-2024 plan to the fourth quarter of 2024.

- While the language in the enabling legislation requires a congestion pricing fee high enough to support $15 billion for the 2020-2024 capital plan, this could be amended if the resulting fee, after enacting exemptions and credits, is deemed too high.

- The MTA increased federal formula funding for 2022 to 2024 by $1.7 billion due to IIJA; federal formula grants for the first two years of the 2025 to 2029 capital plan will also be higher due to IIJA. Furthermore, IIJA includes discretionary funding streams that the MTA may compete for.

- State of New York, Chapter 58 of the Laws of 2020, Part UUU

- These funds will be available because, while maintenance of Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority facilities takes precedence over other parts of the MTA capital plan, the facilities are currently all in a state of good repair and all necessary normal replacement spending has been funded. Therefore, additional revenue may be used to support the capital plan of MTA’s mass transit subsidiaries. Metropolitan Transportation Authority, MTA Bridges and Tunnels staff slideshow, March 2022 Bridges and Tunnels Committee Meeting (March 28th, 2022), https://new.mta.info/transparency/board-and-committee-meetings/march-2022.

- Commitments precede receipt of capital funding.

- The Engineering News-Record calculates two indices: a Construction Cost Index (CCI) based on common labor and materials, and a Building Cost Index (BCI) based on skilled labor and materials. From 2011 to 2021, the average annual increase in the CCI was 4.4 percent, while it was 3.6 percent for the BCI. CBC staff analysis of Engineering News-Record, “City Cost Index – New York” (accessed July 11, 2022), https://www.enr.com/economics/historical_indices/NewYork.

- CBC staff analysis of data from Eno Center for Transportation, Saving Time and Making Cents: A Blueprint for Building Transit Better (last updated April 2022, accessed July 11, 2022), https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1vswm6N0KWt3HS6o2OpOnTUr0JcUzKkjy/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=116025220132372710387&rtpof=true&sd=true

- Commitment data in the report is through the first quarter of 2022.

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, “C&D Contracting: Upcoming Opportunities” (updated July 27, 2022; accessed August 6, 2022), https://new.mta.info/agency/construction-and-development/contracting/upcoming-opportunities.